The past three weeks, Lost in Translation has looked at a number of TV series from the Eighties that could be ripe for remakes. One series, though does stand out from the era that has been remade several times. Let’s take a shadowy flight into the dangerous world of the Knight Rider.

First airing with a two hour pilot in 1982, Knight Rider starred David Hasselhoff as Michael Knight, a man who does not exist. The Foundation for Law and Government, or FLAG, was founded by Wilton Knight (Richard Basehart), who takes a young detective, Michael Long, who had been shot near fatally in the face and gives him a new name and face to become Michael Knight, the prime agent for the organization. However, Michael won’t be working alone. He’ll have with him a prototype, the Knight Industries Two Thousand, an artificially intelligent autonomous car, voiced by William Daniels. To maintain KITT and be available to assist Michael, FLAG has a semi-trailer with high tech lab, where Dr. Bonnie Barstow, played by Patricia McPherson, serves as head technician and Devon Miles, played by Edward Mulhare, provides mission details to Michael and KITT.

The series was episodic, but there were a few recurring villains. The most notable was the Knight Automotive Roving Robot, or KARR, first voiced by Peter Cullen, an evil version of KITT. KARR’s programming focused on self-preservation, leading to the vehicle being mothballed. Learning from the failure of KARR, KITT’s core programming focused on the preservation of human life. KITT cannot allow a human life to be lost, through action or inaction, similar to Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics.

Knight Rider ran for four seasons, with a few changes each year to the concept. Season four saw KITT upgraded with a “Super Pursuit” mode, which modified the car for faster speeds. KITT, though, had a number of standard functions, triggered by button or verbal command from Michael or by KITT when programming allowed, including Turbo Boost and Skiing.

The series had a spin-off series, Code of Vengeance based on a two-part episode that was a backdoor pilot, and a follow-up TV movie in 1991, Knight Rider 2000, which wrapped up what happened to Knight Industries, FLAG, Michael, and KITT, though leaving room for a sequel. Code of Vengeance ran as a mid-season replacement in the 1985-86 TV season, with a pilot movie and four episodes; the series was similar to Knight Rider in that a lone man travelled around to right wrongs.

Moving away from the series, the 1994 TV movie Knight Rider 2010 took its queues from Mad Max. Jake McQueen, played by Richard Joseph Paul, was a smuggler who was tagged to retrieve Hannah Tyree, played by Hudson Lieck, who worked for the Chrysalis Corporation as a programmer. Hannah, to save herself, downloads her consciousness into a crystalline memory core. Jake installs her into a modified Ford Mustang, and the pair go out into the desert to fight for justice.

In the 1997-98 TV series, when syndication was still going on, yet another attempt to reboot Knight Rider came about. Team Knight Rider didn’t buy into the “one man can make a difference”. Instead, TKR was a team of five drivers and their AI cars. Ford had replaced Pontiac as the supplier, so the vehicles represented what could be found at Ford dealerships, with the exception of Kat and Plato, the motorcycles that combined to make the High Speed Pursuit Vehicle. The concept is sound; after all, Michael wasn’t really working alone. He had KITT, Devon, and Bonnie working with him, even if they weren’t always out on the pointy end. A team can do more than a single person. TKR also had a subplot running through the episodes which led to a cliffhanger at the end involving the theft of KITT and the return of Michael Knight. However, early quality issues led to low ratings that even the cliffhanger couldn’t overcome, so TKR ran one season.

In 2008, NBC remade Knight Rider yet again, with Justin Bruening as Michael Knight and Val Kilmer as the voice of the Knight Industries Three Thousand, a modified Ford Mustang. Bruening’s Michael had a link to Hasselhoff’s; he was the estranged son of the original Michael Knight. The new KITT had abilities similar to the original, plus the ability to transform into a Ford F-150, a Ford E-150, a Ford Flex, a Ford Crown Victoria Police Interceptor, and a 1969 Mach 1 Ford Mustang. Three guesses who was a sponsor for the new series. The single sensor bar the original KITT had became two bar above the grill, like a Cylon Centurion being upgraded to an IL-series. Again, the series ran for one season before being cancelled.

Why is Knight Rider the go-to when remaking a series from the Eighties? Granted, it had some longevity in a decade where tastes changed a lot year to year. Hasselhoff’s charisma certainly has a role here, and the apparent chemistry between him and William Daniels despite not meeting until a cast party long after shooting had started. Knight Rider, though, resonates a little deeper with audiences. At its core, the series is about a lone man travelling from town to town and righting wrongs. Several TV series have been built around this concept; from TV westerns like Have Gun, Will Travel and Maverick to science fiction like the Incredible Hulk and even Quantum Leap, which did the same thing with time travel.

Michael Knight is essentially a man on a mechanical horse, whose job is to fight for justice. The series hearkens back to Westerns, but also to Arthurian legends, where a lone knight stood against the barbaric Saxons threatening to ravage the countryside. It’s build into the series name, Knight Rider. KITT isn’t just a mechanical horse; he’s the hero’s sidekick. KITT exists to show how heroic Michael is. KITT, too, is another draw, being a talking car that can drive itself. Today, engineers are working on the nuts and bolts of autonomous cars, running into issues that KITT had no problems with. Horses are better at avoiding pedestrians than self-driving vehicles today. KITT is still just out of reach, but represents a future where driving is made far easier and safer.

The remakes seem to have forgotten the core of the series. TKR had a team, not a lone man fighting for justice. Knight Rider 2010 figured out the concept, but drifted away from the trappings of the original series by going post-apocalyptic. The 2008 remake series picked up from the original series, but reliance on CGI for special effects and KITT being more aggressive left viewers cold. And yet, there are two more potential remakes in the works. The first is a Machinima series helmed by Justin Lin via NBCUniversal. The other is a potential feature film from Spyglass. No other series from the Eighties have had this much attention.

Knight Rider may be the most remade series from the Eighties. Replicating the original success has been difficult because the follow-up series haven’t figured out why the original resonated with audiences. Yet, studios will try to recreate it.

The History of Adaptations

Twenties

Thirties

Forties

Fifties

Sixties

Seventies

Eighties

Nineties

Aughts

Wrapping Up

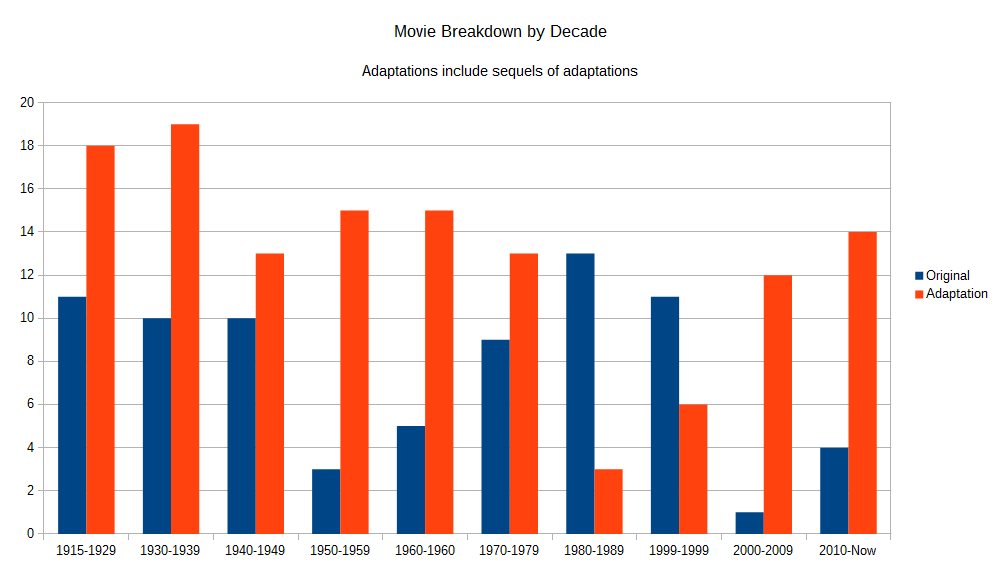

Now that the Teens are done, it’s time to look at the breakdown of popular movies by originals and adaptations. In 2015, Lost in Translation looked at the decade up to that year to wrap up the History of Adaptations series at the time. With five more years gone by, things have changed. Once again, I’m using the compiled list at Filmsite.org.

2010

Toy Story 3 – sequel. Pixar’s most popular series of films.

2011

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 2 – sequel and adaptation. The last of the Harry Potter movies based on the first seven books.

2012

Marvel’s The Avengers – adaptation.

The Dark Knight Rises – sequel of adaptation, The Dark Knight.

2013

The Hunger Games: Catching Fire – sequel and adaptation. Covers the second book of The Hunger Games trilogy.

2014

American Sniper – adaptation of American Sniper: The Autobiography of the Most Lethal Sniper in U.S. Military History by Chris Pyle.

2015

Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens – sequel. The first Star Wars movie released after Disney bought Lucasfilm.

Jurassic World – adaptation. It’s a tough call, as it was marketed as a sequel but doesn’t share much between the original Jurassic Park movies or the book. It’s more, “What if Jurassic Park didn’t have the dinosaur break-out shown in the book and movies?”

Avengers: Age of Ultron – sequel of adaptation. The Marvel movies that led up to this release didn’t make the list.

2016

Rogue One: A Star Wars Story – spin off. The first of several films meant to look at other parts of the Galaxy Far Far Away that aren’t part of the main Skywalker saga.

Finding Dory – sequel of original. The second Pixar film on the list for the Teens.

2017

Star Wars: Episode VIII – The Last Jedi – sequel.

Beauty and the Beast – remake of adaptation. Part of Disney’s series of live action remakes of their animated classics.

Wonder Woman – adaptation. The second DC property to make the list.

2018

Black Panther – adaptation. Diversity matters.

Avengers: Infinity War – sequel of adaptation.

Incredibles 2 – sequel. Another Pixar film, this time fourteen years after the original.

Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom – sequel of adaptation.

2019

Avengers: Endgame – sequel of adaptation

The Lion King – remake. Computer animated remake with photo-realistic characters.

Toy Story 4 – sequel of original and fourth of the series to be mentioned in the History series.

Captain Marvel – adaptation.

Disney is a big winner, with fifteen films listed above. The list breaks down to six adaptations, six sequels of original movies, five sequels of adaptations, two movies that are both sequels and adaptations, and one spin-off. There are no original movies on the above list, the worst showing for any decade. Since popular movies tend to stay in the pop subconscious, the backlash against adaptations has a point. That’s not to say that there hasn’t been popular original movies. Us was knocked out of the top ten of 2019 by The Rise of Skywalker in the final weeks. If anything, the Teens was the decade of the blockbuster, big budget films.

Superhero films were popular, with nine total in the list, including the one not based on any comic book character. Superhero films are filling the niche that Westerns once had, becoming almost ubiquitous. The trend of adapting Young Adult novels that heralded the start of the decade faded; few YA novels ever had the buzz that Harry Potter and The Hunger Games had.

Gone from 2015’s list are Alice in Wonderland, Iron Man 2, Transformers: Dark of the Moon, The Hunger Games, Iron Man 3, Frozen, Despicable Me 2, Guardians of the Galaxy, Inside Out, and Furious 7. The Teens’ top grossing movies come mainly from the latter half of the decade. Part of the losses were to be expected; as the decade continued, more movies had opportunity to outperform what had already come. But the latter half of the Teens had more blockbusters, more record breaking grosses than the first half. Some of it can be chalked up to Disney’s marketing department. The rest of the explanation needs some further study.

As the new Twenties dawn, adaptations hold ground. At this point, it’ll take a sleeper hit to get studios to put the money they do for adaptations behind an original, untested work. Risk avoidance means original works won’t have the spectacle of an adaptation. It may take a well-known name to get an original work done to the same level at this point. For the next few years, expect adaptations to get the lion share of budgets and marketing.

Two announcements got the hackles of fans riled up this past week. First, NBCUniversal announced a new Battlestar Galactica series for their new streaming service, Peacock. The other was a remake of The Princess Bride, via Variety.

Let’s start with the latter. Norman Lear, who produced The Princess Bride, is still active and has a vast library of works that he’s considering for remakes. The new One Day At a Time is just the beginning. However, Variety’s story says that there are people who want to remake the movie, not that there is a remake coming. However, the backlash already from the potential remake shows how fraught adaptation can be. The Princess Bride was released in 1987, over thirty years ago. Thirty years is about how long it used to be between remakes. The difference today is that the originals or most loved versions can be found on DVD, Blu-Ray, streaming, and reruns. The Princess Bride is also a beloved film; it touches the heart while being a fond parody of fantasy. When a fan wants to watch The Princess Bride, it’s not difficult to find the original and introduce new people to the movie. A remake doesn’t have a reason to exist.

Which brings us to the new Battlestar Galactica series. The most recent reboot series ran from 2004 to 2010, so not even out of recent memory. That series came about 25 years after the original first aired, again, a generation later. The 2004 series was a critical success, with tight writing and characters who were far too human. The problem is that a new /Galactica/ series is coming far too soon. The intended audience still remembers watching the 2004 series first run.

Between the two, though, other remakes slipped through the cracks, showing the fandom of The Princess Bride and Battlestar Galactica. Other series being remade for the Peacock streaming service include Saved By the Bell and Punky Brewster. Normal Lear is closer to a remake of Maude than a remake of The Princess Bride. The backlash about those three series being remade is non-existent. All three are at least thirty years old and not on a constant stream of reruns. Maybe the lesson here is to avoid the hugely popular series and movies when looking to remake something and go right for something that is known but not familiar. Doing so will give room to make adjustments for the progress of history.

Three weeks ago, Lost In Translation covered why comedy remakes don’t work. Two weeks ago, Lost In Translation covered the highly successful Airplane!, a comedy remake of Zero Hour!. What’s going on?

For every rule of thumb, there are exceptions. There are adaptations that are better liked than their originals. What should turn the audience off becomes the draw. This happens in many mediums, film, television, and music included; the new work is the better known version, often considered an improvement. How can an adaptation that generally goes against general rules of thumb be popular?

The main reason is that the adaptation does what it intends well. Airplane! set out to be a comedy and is now tenth on the American Film Institute’s 100 Funniest Movies. Young Frankenstein, which could be considered a comedy remake of Frankenstein as well as a sequel and a fix-fic, is thirteenth on the AFI’s list. Both films set out to be funny and they succeeded. Similar to comedy remakes is the anime released as a gag dub, especially when there’s no other way to watch the original. Fan-made gag dubs don’t get the same dislike, because they don’t replace the original work, just spoof it. But when the only way to watch a work is through a gag dub, fans get annoyed. Yet, Samurai Pizza Cats, the gag dub of Kyatto Ninden Teyandee, has a bigger following than its original. With the Pizza Cats, the gag dub came about because the importers didn’t get the original scripts, something Airplane! and Young Frankenstein didn’t have an issue with. Like the two films, Samurai Pizza Cats succeeded in what it set out to do, be funny.

Being good helps, but sometimes just being better known can help. By 1980, Zero Hour! was relegated to late night TV filler, a black and white movie in a colour universe, and not well known to the general audience. Same thing with Kyatto Ninden Teyandee; it came out before the big anime boom of the mid-90s. Samurai Pizza Cats was imported not because it was anime but because the Teenaged Mutant Ninja Turtles franchise was a juggernaut and Saban wanted a piece of the action; the theme song even admits it. Obscurity means audiences can’t compare the two easily. That doesn’t mean that the small fanbase won’t be upset, but the general audience won’t be aware of the original. Young Frankenstein, though, doesn’t have this advantage. Frankenstein is one of Universal’s classic monster movies. Yet, not working from an obscure work wasn’t a hindrance.

Sometimes, the original work, while popular at the time of release, may not have held up well as the years progressed. The original Battlestar Galactica, a space opera family adventure series, represented an older style of storytelling, one that included hope despite the Twelve Colonies being completely destroyed. When the series was rebooted in 2004, the tone changed, growing darker, with the possibility that the ragtag fleet might not make it to Earth. The new series lasted longer than the original and had none of the network interference.

What most of the exceptions listed above do is respect the original work. Airplane! may have spoofed the airline disaster movie genre into non-existance, but the film treated Zero Hour!‘s plot seriously. Likewise, Young Frankenstein picked up from the Frankenstein and showed where the character and not the original film makers made a mistake. It’s the difference between laughing at and laughing with. The exception to this exception is Samurai Pizza Cats, a work that probably wouldn’t be done today because of how anime is treated has changed since the TV series first aired.

There are exceptions and there are exceptions to the exceptions. The one key element in the exceptions is that they are exceptional works, done well by their creators, leaving the audience a sense of satisfaction, not hate.

Last week, Lost in Translation looked at the idea of parodies and how they are different from adaptations. This week, a look at the flip side of parodies, the remake that serves as a comedy vehicle.

A comedy vehicle is a work, typically a movie, that highlights the lead’s comic ability. The plot is secondary to the showcase of talent. This tends to hold whether the work is original or an adaptation. Examples include movies starring Adam Sandler or Will Ferrell. Audiences turn out specifically for the star of the movie. They know what to expect from the film. Even with television, the nature of the star influences the direction of a TV series, /Seinfeld/ being a good example.

That isn’t to say that any movie starring a comedian is a comedy vehicle. A comedy, whether in theatres or on television, requires actors who are aware of the timing needed to deliver lines. For television, a rule of thumb is to check the title. If the title and the lead character are named after the star, ie, I Love Lucy and Seinfeld, chances are it’s a vehicle for the star. The rule isn’t perfect; The Bob Newhart Show was named after Bob Newhart with his character sharing his first name, but it was an ensemble series. With movies, it’s not as clear cut, but the advertising will promote the star as much as the film. To clear up the differences, let’s look at two of Robin Williams’ works. Mork and Mindy was created specifically for Williams after his appearances as the character on Happy Days. Hook, though, was created by Steven Spielberg because of his love of Peter Pan and used Williams’ ability to be child-like in the role of Peter.

Adapting a work to become a comedy vehicle has an appeal to studios. The adaptation has two built-in audiences – fans of the original work and fans of the star. Studios use the star power of the leads in other works to draw in audiences. People know what to expect, whether the movie stars Will Smith, Robert De Niro, Julia Roberts, or Jennifer Lawrence. With adaptations, the popularity of the original acts as the draw. The Harry Potter movies were going to draw crowds, whether they had leads with star power in Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone or not. When a work is a bit more esoteric then attaching a star can help with drawing an audience. In 1982, Philip K. Dick was known to fans of literary science fiction, but relatively unknown outside that circle. Having Harrison Ford, then known for films like American Graffiti, Star Wars, and Raiders of the Lost Ark, play Deckard in Blade Runner could bring in a wider audience.

The problem here is that, with a comedy vehicle, what draws in fans of the original work may get tossed aside. With the Blade Runner example above, Ford was a good fit for the role. With a comedy vehicle, the roles will get changed to suit the actors. Fans of the original may not recognize the new character. In a parody, a change of name to the role isn’t a problem; Captain James B. Pirk is definitely not Captain James T. Kirk, but a mockery. In a comedy remake, that difference gets lost. It’s not too bad when the original is also a comedy, but when it isn’t, audiences start getting mixed reactions.

In general, the change in tone can throw off fans of the original work. Light family fare includes humour to keep the tone light, but the work may not necessarily be a comedy. The work doesn’t have to become a comedy vehicle in order to throw off audiences. Taking family fare and turning it into something dark can result in the same mood whiplash. The difference is that in that case, audiences would be wondering if they and the adapters had seen the same work. When a work becomes a comedy vehicle, it comes across as laughing at not just the original but also the fans. Parodies are up front about their intent and include some space between them and originals. Adaptations that become comedy vehicles lack that separation. It’s the difference between laughing with someone and laughing at someone.

The result is an audience that is turned off from the adaptation. Few people like being laughed at, whatever the reason. This is on top of having expectations dashed, especially if the marketing doesn’t prepare the audience for what the movie really is. The 2009 movie adaptation of Land of the Lost is the perfect example here. It took a Saturday morning series aimed at children and turned it into an movie featuring adult humour, losing the audience who watched the original show who expected and wanted something closer to what was aired in 1974.

Ultimately, adaptations and comedy vehicles have different goals. An adaptation is bringing a work from one medium to another or remaking in the same medium with an eye on bringing in fans of the original. Comedy vehicles exist for the stars and their fans, and plot is secondary. The two approaches are at odds with each other. Unless the comedy vehicle can make allowances, the adaptation will suffer.

After analysing a number of adaptations over the past few years, it’s nigh time to examine how the different sources of material affects how a work is adapted. The History of Adaptations series helped show the different sources that led to popular works, with other works being reviewed expanding the list.

Literary sources cover a wide range, from novels to short stories to plays to poems. Each source has its own challenges for adaptations. Novels, being a longer form, tend to lose details when adapted as films. A series of novels adapted to film can lose critical scenes, especially if the adaptation begins before the last as happened with the Harry Potter series. Television may be the better format for novels; while individual episodes are shorter than a film’s run time, a full season gives more time to delve into the work. With the today’s choices for television going far beyond the three-channel universe, a traditional 22 episode season isn’t needed. Mini-series can take as long as needed. One other means to adapt a novel is to just use the characters and create new situations, such as happened with The Dresden Files. The benefit of novels is that their popularity is easy to track. The New York Times‘ best sellers lists, while flawed still provide studios an idea of how well a title is selling. A novel that makes headlines because of fan enthusiasm makes the choice to adapt it easy.

At the other end of length, short stories may not have enough material to fill a movie’s runtime. Studios would have to extrapolate and expand from the events in the story, sometimes to the point where the film could have been its own work. A television series would not work, unless the idea is to keep the characters in further situations. However, an anthology series could take the story and adapt it. The Twilight Zone did this throughout its run, with episodes like “Steel” and “An Occurance at Owl Creek Bridge” being typical.

Plays don’t have the problem of having too much or too little story when it comes to being adapted as a film. A typical play is performed in about the same time as a film, possibly a little longer. The script is already written; all the director needs to do is remember that the fourth wall is now the camera’s lens instead of the audience. Plays don’t work out as well for television; length is the limiting factor.

Poems and songs do get adapted, though not to the same degree as other literary sources. The poem or song needs to be narrative, providing or at least implying a plot of some sort. “Harper Valley PTA” may be the best example, having been made into a movie that was then adapted as a TV series. The song provided the basis for the plots in both. Popular songs are easy to track, through Top 40 lists and YouTube hits.

Comics are a popular source for adaptations today. The bright costumes, the spectacle of superheroes fighting supervillains, and the almost black-and-white morality of pulp western serials are a lure for filmmakers. Yet, as a serialized means of storytelling, a comics adaptation could easily find a home on television. The plots are already storyboarded, though only Scott Pilgrim vs the World took advantage of that. Right now, the looming problem is audience burnout. At some point, audiences will want something different, but not too different. Yet, comics cover a wide range, something Marvel Studios has been exploiting. Each of the Marvel movies has been superheroes crossed with something else, from technothriller (Iron Man) to heist movie (Ant Man) to romantic comedy (Deadpool). The variety available in comics, not just the superhero titles, makes the medium ripe for the picking. Add in foreign titles, such as manga, and the surface has barely been scratched.

Television looks like it could make the jump to the silver screen. There have been attempts. The problem is the differences in running times. A TV episode today can run either 22 or 45 minutes, with breaks for ads. A full season can each 22 episodes. Neither fit well into a 2 to 2.5 hour film. Expanding an episode is similar to expanding a short story; much more needs to be added. Age of the work is another matter. Some series, like Entourage, have a goal to end with a cinematic release. Other series may have just enough popularity to risk trying a movie, like Firefly and Veronica Mars. The end result may be true to the TV show, but may not get the critical mass needed for an audience. Older series have another issue; while it may have been popular in its day, a TV series may not be well known to today’s audience. The Beverly Hillbillies, while almost note perfect as an adaptation, didn’t have the name recognition needed to get people out to it. Remaking and rebooting a TV series can work, though. Star Trek returned as Star Trek: The Next Generation to a much larger fanbase than the original series had when it first aired. The new Battlestar Galactica lasted longer than the original, providing a different look at the ragtag fleet searching for Earth.

Film remakes are also popular today. There appears to be a roughly thirty to forty year gap between originals and remakes. Take a look at King Kong; ignoring sequels, after the giant ape’s first appearance in 1933, the movie was remade in 1976 and 2005. With home video tape players and, later, DVD and Blu-Ray players along with specialty movie cable channels and streaming services, this gap may need to grow. The availability of older movies in homes grew tremendously in the Eighties. While the 1959 Ben Hur didn’t need to compete with the first adaptation, a remake of Raiders of the Lost Ark has the original available and in many home movie libraries. Adapting a movie to a TV series means further exploration of the film. M*A*S*H and Stargate SG-1 are arguably the most successful film-to-TV adaptations, both having run ten years and are both still available in syndication and on DVD. Not every movie can make the jump to television; the film needs to leave room for further stories featuring the characters.

Video games have had a rough time in adaptation. The early video game movies were either poorly done or completely missed the mark; Super Mario Bros illustrates the latter well. Video games turned out to have similar problems as literary sources. Early games, especially arcade games, had just enough plot to lure players before letting them button mash. similar to the problem of adapting a short story. Later video games, especially once home consoles had the ability to save games in progress, provided for a longer story, requiring several hours of game play. Parasite Eve‘s ten to twenty hours for completion is on the short side. What some adaptations have done is provide extra information for players, either what happened prior to the game or what happened after. Animated adaptations, most in the form of a cartoon like Super Mario Bros Super Show, have been more successful. In most cases, the cartoon just takes the characters and some of the game play and create new stories around them.

Other games, such as boardgames and tabletop RPGs, see similar problems to video games with added layers of abstraction. Clue may have been the best adaptation of a boardgame; the game itself is a murder mystery with a cast of investigators and one murderer, ideal for translating to the big screen. Battleship, on the other hand, tried to incorporate elements from the game but there wasn’t much to bring in, resulting in a mess of a movie. With tabletop RPGs, the problem is that, while there may be an idea of what game play looks like, the game itself is social. Players create their own characters and storylines. Studios are competing with the imagination of the players. Tabletop RPGs are also a niche market; very few games get beyond specialty stores and into book stores.

Toys may have had the best success rate of all sources mentioned here. Most adaptations of toys started as a way to market the toy itself. However, to keep the audience watching, story and character development happened. Cartoons like Transformers, Jem and the Holograms, G.I. Joe, and My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic took the idea of the toy and expanded on it, creating settings and introducing characters. Not every adaptation succeeded; the live action Jem and the Holograms was pulled from theatres after two weeks. The problem studios need to watch out for is reaction by parental groups and popularity of the toy. Captain Power and the Soldiers of the Future ended on a heart wrenching note because while the series had an audience, the toyline did not. Even a mess of a movie, like Michael Bay’s Transformers, can still be a decent adaptation.

On side note, Bay’s Transformers didn’t have continuity issues. The Transformers series already had multiple continuities, with fans well aware that cinematic universes are a thing. Bay may have been well aware of the problems he was going to face and made the one move that brought Transformers fans on board – he brought in Peter Cullen as the voice of Optimus Prime. A loud movie with explosions featuring Autobots and Decepticons fighting kept the fans happy. Getting key details right can go a long way in making a good adaptation.

Not every adaptation is successful, and not every adaptation is accurate. The goal for studios is to overcome the challenges of the source material. There’s a change coming in how television is seen; once a vast wasteland catering to the lowest common denominator, TV is now exploring new ways its format can tell stories. Film, while still seen as the goal for adaptations, is becoming stale, mainly because of remakes, reboots, and other adaptations. The format of the original work may require a hard look at how it is adapted.

Remakes happen. The known element is popular with audiences, for all that people moan about the lack of original movies. Lost in Translation has looked at the problems different sources have when being translated to film, but remaking a movie has its own issues. For most genres, it’s not a problem. People will enjoy the same story over and over, whatever the format. For horror and mystery, there’s a problem.

Horror and mystery rely on tension and the unknown. In horror, it’s a question of when something happens, with setting, lighting, and music the only cues. Mysteries rely on solving the puzzle, following clues to the end. In both genres, knowing the end result takes away from the suspense. The remake of The Evil Dead took the same situation – a cabin in the middle of the woods and a group of young adults – and, while having similar beats to the original, added its own twists so that audiences couldn’t rely on their knowledge of the older movie.

Before the Eighties, most older films could be found either in repertory theatres or on television, either late night or weekend mornings. With the typical time between original movie and a remake being about thirty years or so, a new generation of audience could grow up without having seen the source. The Eighties, though, were when the VCR took off with hardware and available movies coming down in cost to be practical for the home. Specialty cable stations added to the availability of older movies. Today, with DVDs and streaming, if a film exists, it can usually be found somewhere on demand. A movie from the Eighties, ie, thirty years ago, is still available to the next generation of audience. The twists and turns that made an original movie suspenseful now makes a remake predictable. Yet, people want the familiar. Directors of remakes are in a tough spot. The audience wants the remake to be faithful, but not too faithful.

Slasher films and monster movies have an out. Audiences are there to see the star – the slasher or the monster, different sides of the same coin – do what they do best, kill people. Few people watch a Godzilla movie to cheer the Japanese Self-Defense Force; they’re there to see Godzilla stomp through Tokyo. Toho has rebooted the series, but hasn’t really remade the original.

Another issue with horror remakes is that horror films tend to reflect the fears of the time they are made. Going back to Godzilla, the original film was made in response to the growing fears of atomic weapons, made in a country that had the first and only two atomic bombs dropped on it. Other fears that have shown up include machines turning on humanity (Maximum Overdrive, The Terminator), humanity’s interference with nature (The Thing, Sharktopus), loss of identity (The Fly, Star Trek: The Next Generation‘s Borg), the faceless other (zombie films), and the seductive other (vampire movies). While some of those fears are part of being human, others change as understanding is gained and political winds blow.

Mysteries may not rely on the fear of the day, but they do rely on the puzzle. With information at the audience’s fingertips today, it’d be easy to do a quick search to find out whodunit. Adapting a mystery from literature doesn’t quite have the same problem; the audience is there to see a story they enjoyed on screen, not solve the puzzle. Remaking a mystery, though, needs to create new twists to keep the audience on its toes. There are exceptions, such as Columbo where the draw is to see how the detective solves the murder, but most mysteries rely on not knowing who the killer is until the reveal. Even the live action Scooby-Doo, while still using the tropes of the cartoon including having the monster really be someone the kids have met, created its own plot instead of using one of the animated episodes.

There are ways around the problem. The first is to make the new movie a reboot, picking up where the previous film left off. The TV series Ash vs Evil Dead is a continuation of the original The Evil Dead with Ash getting into more trouble. It’s easier with slasher films and monster movies; the star is the attraction, so even with new casting, as long as the main character acts in the expected way, the audience is satisfied. Mysteries may have a harder time, depending on how much the original actor was tied to the character. Peter Falk made Columbo his character; it’ll be some time before an audience will accept a newcomer to the role. However, other characters, like Sherlock Holmes, have been portrayed by a large number of different actors.

The key in any remake is to provide the audience what they expect. With horror, the expectation is suspense and scares; with mysteries, it’s a whodunit. The characters in the remake should behave like they did in the original, even if the plot has changed. Shaggy shouldn’t sound like an Oxford scholar and Ash Williams shouldn’t be the luckiest man alive. Get these details correct, and the audience won’t mind changes to the plot.

The MST3K Remakes:

Reptilicus

Danger!! Death Ray

Robot Holocaust

Manhunt in Space

Manos: The Hands of Fate

Over the past few weeks, Lost in Translation has been looking at how to remake some movies featured on Mystery Science Theatre 3000 Now it’s time to see what the films have in common, besides being not well made. Budget was a huge problem for each movie to the point where going cheap hurt the presentation. However, each film had its own reason for the low budget.

Remaking a bad movie requires that the original film have something worth bringing out. Each movie featured in the past month does have a core idea worth examining. Reptilicus is the first and only Danish kaiju movie; a giant sea monster wreaking havoc somewhere other than Japan or the US could be a draw. Danger!! Death Ray was a Italian spy movie taking advantage of the popularity of the 007 films; a remake could turn Bart Fargo into a franchise that is neither Bond nor Bourne. Robot Holocaust felt like someone’s post-apocalyptic tabletop RPG put to film; remade as a TV series, the setting could be expanded instead of looking like a number of encounters facing the player characters. Manhunt in Space was an early TV space opera; a remake could take a retro-pulp feel, crossing Star Trek with Flash Gordon. Manos: The Hands of Fate was a disaster of a film limited by its budget; remaking it could bring in the horror missing in the original. There is a core that can be dug out.

A large budget isn’t necessarily an instant fix. Battleship is the prime example here at Lost in Translation of a large budget still not leading to either a good movie or a good adaptation. Low budgets, though, mean that the necessities, including competent crew from the grips to the editors, are cut back. The goal is to find the right budget for the movie. A Reptilicus remake would need to invest in the special effects to make the titular monster impressive. A Manos remake, though, wouldn’t need the same budget; indeed, too much money may create new problems* for a film that’s essentially a horror story at the personal level.

Once the budget problem is fixed, the next is fixing the editing. Manhunt didn’t have the issues the other films had; its limitation came from being a TV series from the early days of television. Robot Holocaust needed to be tightened up at points. Reptilicus had a few moments where the limitations of filming were obvious, including a shot where it is easy to tell two different types of film were used, one for the monster and another for the victim being eaten. The other two had worse problems, with editing errors still getting into the released cut.

The format of the remake will be key. Robot Holocaust may be better served as a television series. Its setting needs to be set up and explored, with each of the various factions – the air slaves, the Amazons, the robot overlords, and even the Dark One – getting attention so that they all don’t feel like a check box. Manhunt could work either as a film, albeit one with a sequel hook if Cleolanta escapes at the end like all good pulp villains do, or as a pilot for a TV series about the Space Rangers. Danger!! Death Ray works best as a film, as does Reptilicus and Manos, the first two to take advantage of the large screen, the latter because the story is self-contained.

Special effects, while tied to budget, should be addressed. None had great effects, especially compared to today. The Death Ray remake needs to look like it wasn’t filmed in someone’s tub with Billy’s toys. Manhunt needs to be updated given how far technology has changed since 1954. Reptilicus, the monster, looked very much like the puppet he was. Robot Holocaust had similarly obvious puppets, making it hard to believe the characters were in danger from angry worms. Even Manos, despite having very few effects because of its low budget, could use some upgrades, especially for the Master’s hound. Today, CGI can help fix the problems, but it’s not a panacea. Good effects still won’t help if the rest of the film has problems.

Why remake the films, especially given that the originals weren’t good to begin with? Each of the films were featured on MST3K, whose popularity grew through word of mouth. Manos in particular is better known thanks to its appearance on the series. The audience expectations would be low; any improvements would be a bonus. The expectations could backfire with Manos, though; the draw is because the movie is so bad. As a bonus to studios, there’s already a commentary on what went wrong, MST3K itself.

It’s possible to learn from your own mistakes. It’s also possible to learn from someone else’s. The movies featured on MST3K all have problems. Figuring out what went wrong and how to correct it while remaking the movie is an exercise worth indulging in. Some of the movies may not be easy to remake, and some may be too far gone to be salvageable, but watching them with an eye to where the production made mistakes can help prevent your own.

* To be honest, Manos may be better served being remade as a student project. Today’s off-the-shelf video recorders have far greater capabilities than the 16mm camera used to film Manos, including a far greater record time than 32 seconds. The plot doesn’t need extensive sets or effects.

The short version, adaptations continued to dominate the silver screen. With studios risk adverse, they want to maximize audiences. It’s still not a guarantee of success, but adapting a popular work is one way to draw in a crowd. Couple adapting with popular actors, and studios see a sure thing. The New Teens are looking a lot like the Fifties, where popular adaptations far outnumbered popular adaptations. Let’s break down the top ten films by box office, using the numbers compiled by Box Office Mojo. Remember that popularity isn’t necessarily a sign of quality, just of what is popular.

1) Finding Dory – sequel to the Disney/Pixar original work, Finding Nemo. A surprising entry, given the strength of what follows.

2) Captain America: Civil War – second sequel to Captain America: First Avenger, an adaptation.

3) The Secret Life of Pets – original.

4) The Jungle Book – Disney’s live action remake of its animated adaptation of the story by Rudyard Kipling.

5) Deadpool – adapted from the Marvel character and the most comic book movie ever made*.

6) Zootopia – An original Disney animated movie.

7) Batman v Superman: The Dawn of Justice – adapted from characters and situations seen in DC Comics.

8) Suicide Squad – another DC Comics adaptation.

9) Rogue One: A Star Wars Story – an original movie in the Star Wars franchise.

10) Doctor Strange – adapted from the Marvel comic.

Note that Rogue One and Doctor Strange are still in theatres. The Star Wars prequel could finish 2016 higher in the list and also dominate the 2017 list.

For all the complaints people have about adaptations, audiences went out to see them more than original works. The breakdown has two completely original works, two sequels/prequels to original works, and six adaptations or sequels to adaptations. It’s telling that most of the original works are animated, especially from Disney, who used to plumb animated features from fairy tales. Studios just aren’t going to give up the potential income from popular adaptations, no matter the outcry. At this point, original works will need top talent just to get a budget from studios. Depending on the work, an original may need to go to television just to get noticed. For balance, let’s look at the bottom ten.

10) Whiskey Tango Foxtrot – fictionalized adaptation of the memoir, The Taliban Shuffle: Strange Days in Afghanistan and Pakistan, by Kim Barker

9) Assassin’s Creed – adaptation of the video game.

8) Snowden – a biopic of Edward Snowden.

7) Mechanic: Resurrection – sequel to the remake, The Mechanic.

6) Manchester by the Sea – original.

5) Free State of Jones – loosely based on a historical event.

4) Blair Witch – remake of The Blair Witch Project.

3) God’s Not Dead 2 – sequel to a movie based on Rice Broocks’ God’s Not Dead: Evidence for God in An Age of Uncertainty.

2) Keanu – original.

1) Middle School: The Worst Years of My Life – adapted from Middle School: The Worst Years of My Life by James Patterson and Chris Tebbetts.

Note that Assassin’s Creed is still in theatres after being released on December 21. Manchester by the Sea opened in limited release November 18 and had a full release December 16 and is still in theatres.

The bottom ten has four adaptations, two sequels to adaptations, one original work, and two movies based on real events, including the Snowden biopic. Being at the bottom isn’t necessarily a sign of quality. Manchester by the Sea has been nominated for a number of awards, including Golden Globes for Best Motion Picture – Drama and Best Screenplay, and has been listed on the American Film Institute’s Top Ten Films of the Year. What the bottom ten show is that adaptations run the gamut of popularity and that we’re still in an era where adaptations outnumber original works. However, with two exceptions, every decade in the history of movies shows that trend. The exceptions were the Eighties and Nineties.

Adaptations aren’t going away any time soon. People are still getting out to see them in theatres. At this point, quality is important; repeat audiences are driving the numbers for several films. For now, expect more original works in unexpected media, like animation or television.

* I’d say “shamelessly the most comic book movie,” but the movie lives in audacity, contributing to its popularity.

During a discussion with Steve, the question whether there is a cycle happening, one first started in the Fifties. During the History of Adaptations, the Fifties were discovered to have a low number of original works, something that the Aughts shared. The Fifties also had a number of movie remakes, something the New Teens is seeing.

With the movies remade in the Fifties, the new versions took advantage of the change in filming technology. The Ten Commandments and Ben Hur: A Tale of Christ were both black and white silent films when they were released in the Twenties. Their remakes in the Fifties took advantage of the major advances in movie making – sound and colour. With both films being period pieces, nothing on screen needed to be changed beyond what was essential for the new technologies and grander scales available. The spectacle of both epics were enough to draw in the younger audience while those who saw the originals could see them again with the new dimensions of full colour and sound. Thirty years made a huge difference in the film industry.

Fast forward to now. The entertainment news is filled with remakes. Just from the older news posts for Lost in Translation, I get the following list:

Jem and the Holograms

The Equalizer

Ghostbusters

Predator

Indiana Jones

Blade Runner

Big Trouble in Little China

That doesn’t include films like 21 Jump Street, remaking a TV series, and all the Ninties movies being remade like Stargate. Again, the difference is thirty years. The advances in film technology aren’t as obvious, though. The use of computers for special effects has grown over time, but not all the works being remade will benefit from the advance outside the budget. Cecil B. De Mille remade The Ten Commandments because of the sound and colour. The movies listed above and the others are being done because of nostalgia.

It’s the thirty years that raised the question. Thirty years is enough time for a young man to work through the system to get to the point where he can make decisions on what to film. Thirty years ago was 1985, the middle of the decade with the most original popular works made. The chart from last week may help here.

As pointed out last week, part of the issue with the complaints about adaptations is that the Eighties and Nineties, where the original works outnumber the adaptations, were anomalous. Today, if someone wanted to watch a movie from the Eighties, it’s not difficult. Between television reruns, home video and online streaming, chances are good that a movie from the Eighties is available. In the Fifties, those options weren’t available. Movies from Hollywood’s early years might make an appearance on television or appear at repertory cinemas, but the ease of finding them did not exist like it does today.

Is there a cycle restarting? It’s hard to tell. There isn’t enough data yet to make that call. The chart above shows that the New Teens are behaving in a similar manner to the Sixties, but this decade is only half over. A backlash against adaptations is building, but, again, the Eighties and Nineties were exceptions, not the norm, when it comes to original works. It is something to keep an eye on, though. If a cycle is repeating, noting the speed at which the elements appear helps work out how long a given segment will last.