Time to wrap up 2021 with a look at the box office for the year. As usual, the list comes from Box Office Mojo.

- Spider-Man: No Way Home – sequel to Spider-Man: Homecoming, which itself was a reboot of an adaptation.

- Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings – adaptation of the Marvel character.

- Venom: Let There Be Carnage – sequel to Venom, an adaptation of a comic that reached top ten in 2018[https://psychodrivein.com/lost-in-translation-wrapping-up-2018/].

- Black Widow – adaptation of the Marvel character.

- F9: The Fast Saga – the most recent sequel of the franchise, The Fast and the Furious, itself an original film.

- Eternals – adaptation of the Marvel characters.

- No Time to Die – the lastest sequel of the 007 franchise.

- A Quiet Place Part II – sequel to 2018’s A Quiet Place.

- Free Guy – original work.

- Ghostbusters: Afterlife – sequel to the original 1984 film, Ghostbusters.

Getting the obvious out of the way first, Marvel superheroes are represented by half the films in the list. Blockbusters are well represented on the list. With theatres opening up in 2021 thanks to vaccines and masking mandates, pandemic precautions were reduced and, in some areas, rescinded. That gave studios a chance to bring out the big guns they had waiting. Of course, the re-opening may have been too soon, with restrictions looming once again.

As can be seen on Box Office Mojo’s domestic yearly box office list, the gross at theatres is up by double over the previous year. That’s a start, but considering that 2020 saw a massive drop in theatre revenues thanks to pandemic lockdowns, double isn’t much. It’ll take time.to get people back in seats.

Back to the list, there’s an original work, Free Guy, starring Ryan Reynolds. The last time an original work was in the top ten was 2016’s Zootopia. With Free Guy, Reynolds is the draw. He has a charm that comes across easily in a film no matter the role. This time out, he’s playing a nameless NPC in a video game who has managed to get a glitch in his programming.

I’m adding a new category this year, the franchise sequel. The definition is still nebulous, but anything film that is part of a franchise that uses the same characters and/or situations counts as a sequel. F9: The Fast Saga is a good example of a franchise coming from an original work while No Time to Die is part of the 007 franchise. No Time to Die is also continuing the trend in 007 films of using an original story after the franchise has used almost every title it could from Ian Fleming’s works. It could be argued that some of the Marvel movies are now franchise sequels as the Marvel Cinematic Universe has taken on a life of its own separate from the comics’ continuity.

The two sequels of original works, Ghostbusters: Afterlife and A Quiet Place Part II are almost opposites in the approach. A Quiet Place Part II got delayed thanks to pandemic lockdowns and was kept waiting on the sidelines until things opened up a bit. The delay didn’t hurt the response, with audiences wanting to follow the family from Part I. Ghostbusters: Afterlife is a sequel to Ghostbusters and Ghostbusters II, released thirty-two years later.

Taking the above into consideration, superheroes aren’t going anywhere any time soon. While people may be getting tired of the name Marvel, the films are staying fresh by being other genres with superheroes added. Black Widow is a spy thriller with superheroes. Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings is wuxia with superheroes. If one Marvel movie isn’t interesting, the next one might be. As long as the studio avoids continuity lockout, where an audience needs to have watched all of the previous films for a plot point, Marvel can keep going.

The above shows what 2022 could look like, with lockdown returning early in the year before being lifted once again when the number of COVID-19 cases drops. The real surprise was seeing an original work on the list. Granted, it starred Ryan Reynolds, but with 2021 having less than half the releases that 2019 saw, there was room for an original work to sneak in, leaving the possibility open for an original work to reach top ten in 2022.

(This column is posted at www.StevenSavage.com, www.SeventhSanctum.com, and Steve’s Tumblr)

I found Failbetter Games browser-based adventure game Fallen London via it’s Kickstarted sister game, Sunless Sea, a kind of nautical rogue like of comedy-horror-adventure. I quickly took to Fallen London’s playable-novel style of adventure (in fact, moreso than the brilliant but nerve-wracking Sunless Sea). As I played this game I began to wonder just why I had taken to it so much – enough to get a monthly subscription for extra elements. That’s where this essay comes in.

It’s clear this award-winning browser game has a certain something that compelled me and others. By getting my own thoughts together here I hope to make a small contribution to game analysis, as well as understand my reactions. Fallen London got me thinking about game mechanics in surprising ways, and a good analysis should help me – and others.

So let’s look at Fallen London – and what it does right. Join me, Delicious Friend.

The Basics of Fallen London

In Fallen London you’re a newcomer to the Victorian subterranean city, which was London some thirty years ago until it was stolen below ground by strange forces. Now under control of the mysterious if often friendly Masters of the Bazaar, nominally ruled by the “Traitor Empress” that made a deal with them, it’s a haunted, weird, scary, and wonderful place. Hell is nearby and has an Embassy, living objects come from distant shores of the underground “Unterzee” and previous stolen cities ruins lie around. Also, people are mailing cats.

You walk into this as a newcomer, arrested for some reason (likely just coming there), and upon escaping embark on your own destiny. Poet, spy, mercenary, investigator, and more all are available to you. As you progress you make connections, improve your character, find lodgings, unlock further secrets, and so on. Whatever you do is up to you.

All of this happens with very well-written text and story vignettes that really bring the half-horror half-comedic setting to life. Fallen London, bluntly, is probably better written than most any game and quite a few books, somewhere between Monty Python, Eldritch Horror, and Discworld.

As I analyzed it I was able to find six areas that the game did things right. These traits and mechanics, in combination, produce a marvelous experience.

Let’s take a look.

Fallen London’s Writing Writing: Expressive, Layered, Personal

It’s hard not to go on about the writing in Fallen London. Were it simply a series of novels or a comic series it’d be an epic experience on its own. The fact this writing is couched as a game makes it even more compelling as you live the writing. This excellent wordsmithing succeeds due to three factors:

Writing Comes First. It’s very clear that the writing of Fallen London is meant to be of the highest quality. The tale-telling clearly has come first over all else, bringing you into the setting, but also making the choices and usual actions of an RPG have a particular urgency and life to them. The writing is not just witty and illustrative – it makes your choices feel real, and the choices and plots are well-thought out.

Branching And Combining Stories. Various conditions unlock story options, stories have multiple resolutions with real impact, and the end of one of the tales may lead to several others. This produces clear choices that feel very real – and are often real as they will lock future choices on one hand, while opening others or at lest providing resources to open them.

Parts Of A Whole. Though there are many stories and “storylets” great care has been taken to make them part of a whole. A mysterious squid-faced man handing you a chunk of slimy amber isn’t a random event, but is due to a backstory. A marsh filled with giant mushrooms isn’t just a marsh, but the site of races as people have discovered that running across giant mushrooms is rather sporting. Everything is connected (finding these connections could occupy you quite a bit in the game).

Abstract Characters. One of the most curious elements of Fallen London is most characters are referred to by abstract names – the Wry Functionary, the Knuckle-Scarred Inspector, and so on. Instead of making them distant this abstraction makes them archetypical, giving them life, while also making the experience personal and unique. Everyone may encounter a Sardonic Music-Hall Singer, but it’s their own, personal one.

Attributes And Failure States In Fallen London: Clear, Abstract, Applicable

Representing characters with various numbers is a classic element of role-playing games. Fallen London is no different, but does it with a mix of generality, clarity, and precision.

Distinct Attributes. Characters are represented by four different Attributes – Watchful, Shadowy, Dangerous, and Persuasive. These Attributes affect a character’s chance to succeed at an appropriate task with a simple random “roll,” and a success provides colorful descriptive text as well as various rewards This simplicity makes characters and characters easy to understand – but also distinct depending on how high that Attribute is.

Attributes Associated With Settings. Various areas of the setting are associated with the activities requiring a given Attribute or Attributes. A monster-haunted area may yield mostly Dangerous tasks, while a street of crime and mysterious couriers may have mostly Shadowy activities. The limited but distinct sets of Attributes in turn allows for easy definition of various areas of the game and the stories within, as well as what one may do there.

Distinct Failure States. Each Attribute has a parallel failure state called a Menace that usually increases if one fails a more severe challenge – for instance failing a Dangerous challenge may result in an increase to Wounds. One can usually guess the probable results of a failure state from the Attribute involved and the descriptive text. The failure states also contain witty descriptions, such as one where spending time with a Vicar raises the Menace of Scandal when said Vicar turns out to be a reporter in disguise who assumes less than pure intentions. Failure is a story.

Unique Results Of Failure States. The Menaces can be treated by specific actions, such as taking Laudanum to deal with the Menace of Nightmares. In addition, if Menaces get too high then the character you play suffers specific effects, such as being imprisoned for having too much Suspicion. Addressing these challenges leads to further stories, making the tale one experiences both appropriate and unique.

Acquired Traits: Linear, Distinct, Multiple

As the character adventures, they make friends, solve cases, advance in the ranks of clubs, and so on. Representing these is done distinct from the attributes in question, often as the result of an action.

Achievements By Simple Numbers. To represent the connections people make, achievements and reputations and so on, there’s simple number scores characters acquire. These represent everything from how good a thief they are to how well-connected they may be to the police. A character may have many of these or only a few – it depends on the activities of the characters. This simple method allows for very complex character differences all with different “piles” of simple numbers.

Reputation As Number. Depending on how a character dresses, their home, and how they comport themselves, they get reputations – Bizarre, Respected, etc. that also have simple number scores, much like Attributes. The items that influence these traits, of course, often have clever and witty descriptions.

Use Of Acquired Traits. Acquired traits open up new story opportunities or may even be used like Attributes in some occasions, such as using one’s Dreaded reputation to threaten someone. Thus these acquired traits become goals, rewards, and tools while just being simple numeric stores. The drive to upgrade them also helps propel some of the game, and may inspire players to upgrade equipment and Attributes.

Progress In Fallen London: Numerical And Relevant

Progress in various ventures in Fallen London is measured by numeric scores, much like the acquired traits.

Progress Is A Number. Progress in almost anything is represented by a simple number score, often raised by challenges against Attributes or exchanging certain items. One may be “Solving a Case” and solve it when one has a score of ten. Or one may be exploring an area and solve it when one has ten points of “Exploring.” These scores are like very temporary Acquired traits, and often reset when a venture is over. These provide clear, simple measurements of progress.

Progress Influences Story. At a certain amount of “points” gained towards knowing a character or group you may unlock options such as starting a romantic relationship. Other scores may increase the challenge, such as solving a case getting harder the further one progresses, with new challenges arising. The score becomes a signal of challenges to come as well as a goal (and a player may feel their heart race as a score climbs . . .)

Negative And Conflicting Progress. These progress scores may, at times be negative or even conflict. One may be trying to outrun a rival, and as “progress” increases the rival is closer. Or one may be trying to keep one score up and another down. A few simple numbers can lead to complex stories and decisions.

Inventory; Abstracted, Related, Storied

Having a large inventory of “stuff” is a time-honored RPG tradition, and Fallen London is no different. However it uses the “adventurer inventory” to cover a wider range of ground, representing possessions far differently.

Everything As Inventory. Anything in one’s possession is portrayed in inventory, but this goes beyond guns or treasures. Possessions can also include knowledge, stories, or insights (each with its own description). One may thus have 1000 Clues or 50 different seafaring stories from their ventures – treated and inventoried no different than 70 pieces of Jade or a mysterious pistol. By treating everything as inventory the game allows a unique way to measure progress and address challenges – one may need to blackmail and enemy, and that story requires 3 Blackmail Materials (which a handy intriguer may have handy).

Inventory Presents Story Options. An item in your inventory isn’t just something to sell or “spend” for a challenge, be it pearls or an Appaling Secret. Inventory items often provide other story options when you select them, from acquiring other items to opening more stories, to helping you solve mysteries. A single kind of item might open up multiple options, giving you different ways to use them – each with their own descriptive text or substorm. One of my favorite examples is having Appalling Secrets – one option in using them is to try and “forget” a few of them with the hope of reducing Nightmares.

Inventory Converts. Another brilliant innovation in the game is that related items, from treasures to knowledge, can often be traded up in the associated “story options” mentioned. Hints become Clues, Jade can be traded for artifacts, candles traded to a church in return for mysterious salts. “Trading up” and at times “trading down” is required to unlock stories or do tasks, and figuring this out is an interesting challenge that contains its own miniature tales. One of my favorites experiences realizing that treasures I’d gathered in a seafaring venture could be swapped up to get information that in turn I could trade for a map to let me continue my adventures.

Economics: Omnipresent, Clear, Varied, Storied

As noted, some of Fallen London is about swapping various items or literal pieces of knowledge to achieve different goals. The entirety of Fallen London is actually about economics.

Progress Is Transactional. All of the well-written stories in Fallen London are essentially accessed by a transaction. This could be swapping a “move” to achieve something, or as complex as figuring out how to “grind” for information to get a legal document in order to get your hands on some important books. As these transactions are clearly stated and often work in a similar manner, the game is very easy to pick up – but the challenge is figuring how to pull off the transactions. After all you may want to save those Whispered Hints to solve a bigger mystery later, or your need to get your hands on seditious material requires you to choose between stealing from a group of Devils or getting into a fistfight with a book-carrying critic.

Tradeoffs Requiring Thought. The economics of the game also require one to consider tradeoffs. One may reduce the Menace of Nightmares with a good cup of wine, but a drunken night may raise the Menace of Scandal, which is best addressed by spending a few turns going to Church.

And So Our Analysis Of Fallen London Ends

So those are my initial thoughts on what makes Fallen London work. To sum it up I’d say it’s a writing-centric game that uses a series of simple scores and inventory systems in combination to allow for complex tales, and has simple but interesting ways to portray common game mechanics and choices. That is, of course, a simple summary.

Now as for what else we can learn, let me see where my investigations – and you reaction to this essay – take us . . .

– Steve

With announcement after announcement of adaptations being optioned, there`s a fatigue building. Even sequels are starting to suffer. As seen in the History of Adaptations, this decade is shaping up to look like the Fifties, where adaptations reigned supreme. In the Fifties, there were three popular original movies and two were Cinerama demos. In this decade, of the four original movies identified on the Filmsite.org list, three are sequels and just one, Inside Out, is original. The analysis of this decade will have to be redone once it’s over, to take into account films like Deadpool and the Marvel Cinematic Universe offerings. Suffice to say, adaptations are dominating this decade.

Not helping with the fatigue is the source of the adaptations. Unlike decades past, adaptations this decade are coming from what could be considered “low-brow” entertainment – comics, Young Adult novels, and movies of the Eighties and Nineties. As seen in the History wrap up, the sources of adaptations in the Fifties came from literary works, with the only Children’s Lit work adapted becoming a Disney movie, Lady and the Tramp. Today, what is considered works solely for children and adolescents – comics, Young Adult Lit, and Harry Potter – are making up the bulk of the popular movies; but all the sources are popular across age barriers.

Some of the fatigue may stem from perceived snobbery; studios aren’t making “grown-up” films, not like the past. That’s not the only source of fatigue, though. Like the Fifties, this decade is seeing remakes of movies from twenty to forty years ago. Ghostbusters, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and even Jem and the Holograms all reach back to a nostalgia for the Seventies*, Eighties, and Nineties. The Eighties were the first decade in movie history where popular original works outnumbered popular adaptations. Indeed, the Eighties saw experimentation in all forms of entertainment – movies, music, television, novels – because no one could predict what would be a hit. Follow-the-Leader maneuverings by studios weren’t guaranteed to be successful, while a low budget movie based on a nightmare, The Terminator, grabbed audiences’ attention. Unlike the Fifties, where the remakes added elements like colour and sound that weren’t possible in the Twenties, the difference between film technology today and in the Eighties is primarily effect based, specifically, CGI. To give a remake its own identity, changes are made elsewhere, such as the flipping of genders in the Ghostbusters remake.

Changes, though, strike at the heart of both the feel of a movie and at nostalgia. With social media allowing voices to echo across the Internet faster today than any previous decade, a film doesn’t have to even be released before critics denounce it. Yet, shot-for-shot remakes lead audiences to wonder why they just didn’t watch the original, something that is easy to do thanks to home video, DVD, and online streaming. Gus van Sant’s remake of Psycho may have had some subtle techniques, but the general audience saw a shot-for-shot remake.

The big problem is the risk aversion seen in Hollywood today, at least on the silver screen. Today’s budgets mean that movies need to pull in as many people as possible, and the easiest way to do that is to adapt what’s popular in other media. Worse, movies like the Harry Potter series, which made an effort to be accurate to the original books, have upped the expectations of audiences. Adaptations that pay lip service to a popular work aren’t going to survive long in theatres, much like Jem. But the adaptations that do pay attention to the source get butts into theatre seats. The record for highest grossing movie keeps getting reset year after year by adaptations this decade; this can’t happen without people going to see the movies. People may be clamouring for original works, but they keep going to adaptations.

If the big screen is becoming dominated with adaptations, where can an original work be found? Television. While there are several adaptations on the air today, including Supergirl, Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., A Game of Thrones, and The Shannara Chronicles, the nature of today’s thousand-channel universe means that adaptations can’t fill every time slot. Reality TV, once a dominating genre, doesn’t allow for reruns; once someone wins the season, there’s no point to watching the previous episodes, which means no sales of boxed sets for holiday seasons. Meanwhile, popular series, from those airing on broadcast channels to cable-only offerings, have a secondary market. The competition between stations, even taking into account time-shifting, means that TV shows have to stand out from the crowd. For now, television is where originality will shine.

With movies, though, until there’s a series of massive flops, adaptations are going to be the order of the day. Studios, though, aren`t going to allow a big budget blockbuster to bomb if they can help it, and have checks and balances and Save the Cat to prevent huge losses. A flop these days only comes about when a studio misjudges the audience response to a project, as what happened with both R.I.P.D. and The Lone Ranger. In the former, it was a comic book movie based on a comic that wasn’t known to the general audience. With the latter, the nature of Westerns had changed greatly as audiences’ understanding of history has changed since the last Lone Ranger movie to the point that Johnny Depp wasn’t the instant draw the studio expected.

The only way to get studios to consider original works is for one to become an unexpected hit. Nothing gets Hollywood’s attention more than the surprise hit. Sure, there will be a number of follow-the-leader movies as studios try to figure out why the film was a hit, but that should spur a few original works, avoiding all-adaptation all the time.

* It could be argued that The Rocky Horror Picture Show became the cult hit it is during the Eighties thanks to repertory theatres.

(This column is posted at www.StevenSavage.com, www.SeventhSanctum.com, and Steve’s Tumblr)

As noted due to my interest with No Man’s Sky I’m blogging about it as it fits my interests in computers, media, and of course procedural generation!

I’m looking forward to No Man’s Sky. I expect it to be a hit. I expect it to be huge. I’ve also wondered that after that “huge hitness” what’s next for i?

This is worth asking because if NMS is a hit, what happens afterwards may be a model for other, similar properties. NMS’ broad scope and procedural content make it stand out – but as there’s many procedural games with broad scope out there and/or coming.

Or in short, I assume what happens to NMS may provide a template for future games and concurrent ones. I want to try and guess now.

Here’s a few things I see:

* GO LONG TERM: It sounds like NMS is going to be around for awhile, and with a galaxy to explore there’s certainly many places to go. We’ve seen long-term games with broad content have endurance (Minecraft, Terraria) and others with similar ambitions (Starbound). NMS is something I can see people playing obsessively, though . . .

* NEEDS MORE: Even hough I’m jazzed for it, I’m not sure the current content set would keep me playing regularly beyond 3-6 months. I think NMS will need to add more content and features over time to maintain interest, else it’ll be for dedicated explorers (which may be the goal). Dedicated explorers would probably play this for 1-3 years.

* MAY ENTER PUBLIC CONSCIOUSNESS: NMS has been on Colbert, been in the news, it’s got the kind of buzz that could make it become “A thing” like Minecraft – something everyone hears about and many try. If successful, it will inspire others to try the same thing (much as Minecraft did), and may give it a longer life. That will also inspire imitators (I imagine at some point procedural games will become comparatively common). That gives it more life.

* WILL LIKELY GO TO ALL PLATFORMS: If NMS is the big hit that I suspect it is, I think there will be an obvious effort to get it to other platforms (I’m at least sure Microsoft will want it on X-Box, but I think the X_box will become a sealed PC next iteration so it might not be an issue). There’s no reason not to extend it, and I imagine there’s demand. (The fact Starbound is on X-Box intrigues me)

* HOW FAR CAN IT GO? The limit of NMS is that its own limits work against it. Hard/impossible to find people. No/little building or influence. As big a booster as I am I’m not sure how far NMS will go before it seems that there’s not as much interest. People do like interaction and exploring and pimping out equipment isn’t like building castles. I also wonder how much they can add on to a game with so much procedurally balanced content.

My prediction on NMS is that it’s got up to 5 years of life in it, but I can’t see it bearing large expansions.

However, an interesting question is how it could not be expanded on, but retrofitted. With all that code and all that work, it might be better if Hello Games focused on No Man’s Sky II and made it truly long-term.

– Steve

Sometime back, Lost in Translation looked at the intricacies of adapting tabletop role-playing games to a different medium. There haven’t been many such adaptations. Lost in Translation has looked at three, the Dungeons & Dragons movie and the animated adaptations of Heavy Gear*, and Dragonlance. There aren’t many more; Fox aired a short-lived Vampire: The Masquerade series called Kindred: The Embraced, and Dungeons & Dragons and BattleTech both had their own cartoons.

The usual approach with adaptations and tabletop games is that the RPG is adapted to a video game. From the earliest Rogue-like games to massive multiplayers like World of Warcraft owe a lot to Dungeons & Dragons. But adaptations in other media are next to non-existent. The failure of the Dungeons & Dragons movie may have a role, but other factors are at work.

The biggest factor is name recognition. D&D is the 800 pound gorilla in tabletop RPGs, with name recognition outside the hobby. Few games even come close to the sales figures or the longevity of D&D. In the 80s, TSR even bought television ad time for the game. D&D, though, is atypical. Marvel tried releasing a game, Marvel Universe Roleplaying Game, but cancelled the publication when the RPG did not see the returns of D&D or Marvel’s own comics. RPGs are a niche market; the built-in audience is not enough to risk a budget on.

Next, the nature of a typical RPG means there aren’t many iconic characters and next to little plot to adapt. Most games allow players to create their own characters, with the Games Master creating the plot and adjusting it in reaction to the players’ actions. A few games, including D&D, don’t come with a setting, though they are in the minority; even those games have published campaign supplements for groups that don’t have the time to create their own world. Even the published settings take on different lives once the players and GM start playing. The Traveller fandom even has acronyms for this phenomenon – OTU, or Original Traveller Universe; IMTU, In My Traveller Universe; and IYTU, In Your Traveller Universe. Movies, books, and stage plays all need characters and a plot. That isn’t to say that there isn’t a typical adventure for RPGs. The classic D&D adventure involves exploring an underground structure fill with monsters while a Traveller adventure has the players travelling the space lanes earning money through speculation and working for patrons. It just takes more effort to come up with a plot and characters that fit a setting than adapting a work that falls under a more traditional form of storytelling.

Game play may be the most difficult part of adapting a game, though it may not be as important as the above. The main goal for a gaming group is to have fun, whether through mindless mayhem, intense angst, or delving into the unknown. It’s a gathering of friends who can take the time to catch up with each other and josh around. There’s banter both in-character and out, with inside jokes coming up. Action in-game can take less time than it does for the players to resolve the action. Combat taking less than a minute can eat up most of a gaming session. Conversely, some actions that would take hours can be resolved with a die roll or two. The pacing is different to traditional storytelling. The dice introduce an extra element; chance. There isn’t a sure thing in RPGs; sometimes, the dice just roll poorly. In a narrative, random failure is jarring. Failure has a purpose in a plot, and doesn’t come up otherwise. An adaptation, though, can throw the equivalent of a failed die roll as a setback for the characters. Failure isn’t always fatal.

Game mechanics, however, do need to be adapted well. Not necessarily the die rolls, but the appearance of details such as spells, weapons, and opposition. The Dragonlance animated movie has a scene where the adaptation got a spell detail wrong; Fizban in the novel cast fireball but, on screen, the spell shown looked more like flaming sphere. While the two spells sound similar, fireball is the more potent of the two, being more explosive and damaging. Details are the devil that make or break an adaptation; getting something like a spell’s appearance wrong can lose a knowledgeable audience, leading to poor word of mouth.

Given the above, it is still possible to adapt a game well. As mentioned above, tabletop games have been adapted and adapted successfully as video games. D&D was one of the first with the gold box series of computer games and both Vampire and Shadowrun have had success in the electronic realm with Bloodlines and Shadowrun Hong Kong. The ability for a player to create a character is a plus in the video game realm, allowing the player to personalize the experience. There have been tie-in novels for several game lines. But of the existing adaptations, only one, the BattleTech cartoon, came close to having the right feel. Even Kindred: The Embraced had issues, such as vampires out in broad daylight, and lasted eight episodes.

Adapters need to understand the source material, no matter what the original work is. With tabletop RPGs, the nature of the games have a different focus. The storytelling in interactive with rules acting as framework and setting physics. Failing to take the mechanics into account leads to characters that don’t quite fit the setting, a setting that only has superficial resemblance to the original, and action that just isn’t possible in the game. The result can be much like the D&D movie, disappointing to fans of the game and incoherent to the casual audience. Adapting a tabletop RPG well will take an effort that may be more than potential returns, leading to the dearth of adaptations made.

* Technically, Heavy Gear was written to be both an RPG and a wargame when it was first released.

** Not all, but, in general, audiences appreciate at least a token plot even in a character piece. Something needs to happen.

During a discussion with Steve, the question whether there is a cycle happening, one first started in the Fifties. During the History of Adaptations, the Fifties were discovered to have a low number of original works, something that the Aughts shared. The Fifties also had a number of movie remakes, something the New Teens is seeing.

With the movies remade in the Fifties, the new versions took advantage of the change in filming technology. The Ten Commandments and Ben Hur: A Tale of Christ were both black and white silent films when they were released in the Twenties. Their remakes in the Fifties took advantage of the major advances in movie making – sound and colour. With both films being period pieces, nothing on screen needed to be changed beyond what was essential for the new technologies and grander scales available. The spectacle of both epics were enough to draw in the younger audience while those who saw the originals could see them again with the new dimensions of full colour and sound. Thirty years made a huge difference in the film industry.

Fast forward to now. The entertainment news is filled with remakes. Just from the older news posts for Lost in Translation, I get the following list:

Jem and the Holograms

The Equalizer

Ghostbusters

Predator

Indiana Jones

Blade Runner

Big Trouble in Little China

That doesn’t include films like 21 Jump Street, remaking a TV series, and all the Ninties movies being remade like Stargate. Again, the difference is thirty years. The advances in film technology aren’t as obvious, though. The use of computers for special effects has grown over time, but not all the works being remade will benefit from the advance outside the budget. Cecil B. De Mille remade The Ten Commandments because of the sound and colour. The movies listed above and the others are being done because of nostalgia.

It’s the thirty years that raised the question. Thirty years is enough time for a young man to work through the system to get to the point where he can make decisions on what to film. Thirty years ago was 1985, the middle of the decade with the most original popular works made. The chart from last week may help here.

As pointed out last week, part of the issue with the complaints about adaptations is that the Eighties and Nineties, where the original works outnumber the adaptations, were anomalous. Today, if someone wanted to watch a movie from the Eighties, it’s not difficult. Between television reruns, home video and online streaming, chances are good that a movie from the Eighties is available. In the Fifties, those options weren’t available. Movies from Hollywood’s early years might make an appearance on television or appear at repertory cinemas, but the ease of finding them did not exist like it does today.

Is there a cycle restarting? It’s hard to tell. There isn’t enough data yet to make that call. The chart above shows that the New Teens are behaving in a similar manner to the Sixties, but this decade is only half over. A backlash against adaptations is building, but, again, the Eighties and Nineties were exceptions, not the norm, when it comes to original works. It is something to keep an eye on, though. If a cycle is repeating, noting the speed at which the elements appear helps work out how long a given segment will last.

The History of Adaptations

Twenties

Thirties

Forties

Fifties

Sixties

Seventies

Eighties

Nineties

Aughts

New Teens

Welcome to the history of adaptations. I’ve been looking at the top movies of each decade, analyzing them to see which ones were original and which ones were adaptations, and of the adaptations, what the source material was. I’m using the compiled list at Filmsite.org as a base. With the New Teens completed up to now, it’s time to figure out what all this means.

First, though, my methodology. I needed a start point, thus my use of the list at Filmsite.org. The list provided me with a base to work from. I chose the popular films, as according to box office, because the films should be memorable enough and have lasting impact on films even today. Even Ingagi, released in 1930 and pulled when it was discovered that the found footage was found in other movies, still has ripples in the form of Gorilla Grodd, who has appeared in the current TV series, The Flash. While box office takes reflect how much money a movie made at the theatres, it does ignore the effects of television airings and the sale and rental of home videos, both video tape and DVD/Blu-Ray. Some classic films, including Casablanca and Psycho, gain an audience long after leaving theatres. Popular films also may not be representative of the films released. There aren’t many Westerns on the list, yet the genre was a staple for several decades.

Going through every film released, though, would be a huge undertaking. The goal of the project was to discover whether movie adaptations were a recent approach or if it was something happening throughout the history of film. The Filmsite.org list starts with 1915’s The Birth of a Nation. One hundred years of film history to examine. I needed a way to get a sample of what was released. Again, the popular films may not be representative. Statistically, I haven’t run the numbers. In the more recent decades, studios have shown a tendency to follow the leader; if one studio has a breakthrough hit featuring an alien invasion/romantic comedy, every studio will make a similar film to get a piece of the action. Whether that holds true for the earlier years of Hollywood remains to be researched.

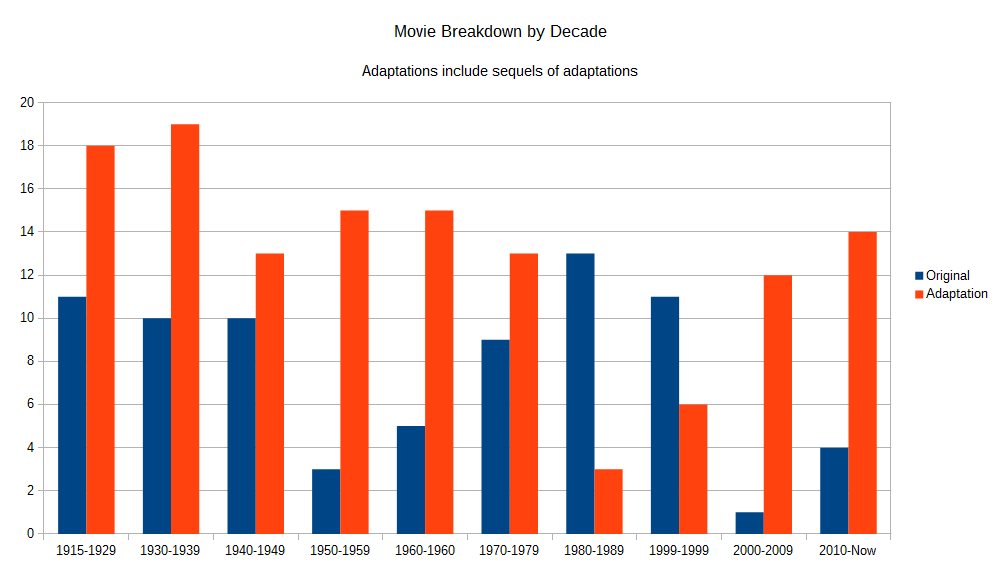

Throughout the project, I broke down the films into original and adaptations, making note of where a film didn’t quite fit into either. I placed sequels under original unless the sequel itself was based on another work. Movies like Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King and The Hunger Games: Catching Fire are both sequels and adaptations, both being based on books in a series. The categories aren’t perfect, though breaking the movies into finer categories would dilute the numbers to the point of uselessness. The most films in one decade was 29, in 1915-1929 and 1930-1939. The fewest, 13, came in 2000-2009, which was also the decade with the fewest original works on the Filmsite.org list. The graph below shows the number of original movies versus the number of adaptations by decade. On the left, in blue, is the number of original works. The right, in orange, is the number of adaptations.

As the above shows, only two decades had the number of original movies outnumbering the adaptations. With all the complaints about the number of adaptations, the Eighties and Nineties, still fresh in people’s minds, were the exception. My expectation when I started was that the early years would have a large number of adaptations as scripts for stage were repurposed for film, but the Fifties showed otherwise. The Fifties were the first decade to have a huge number of remakes, too.

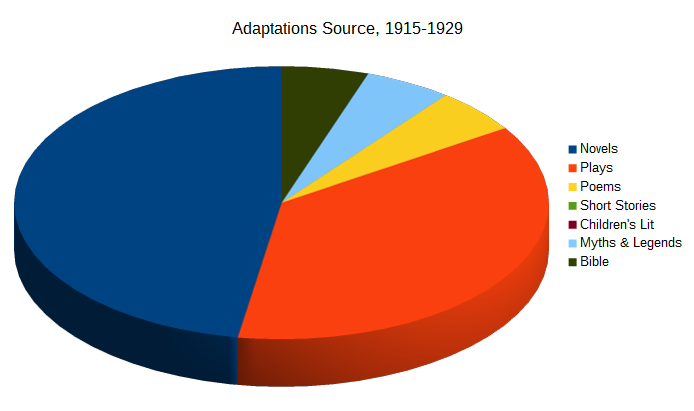

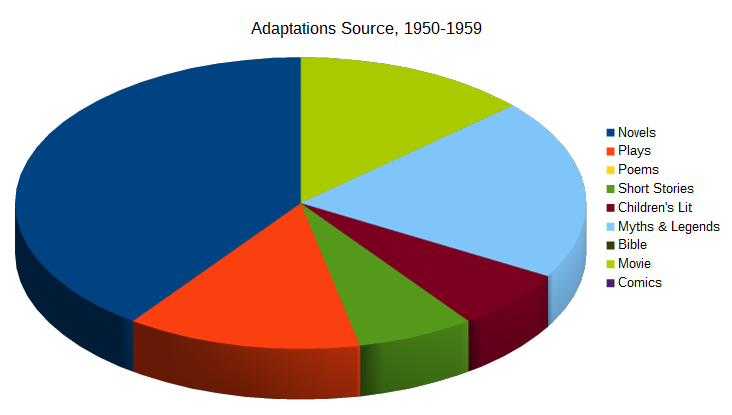

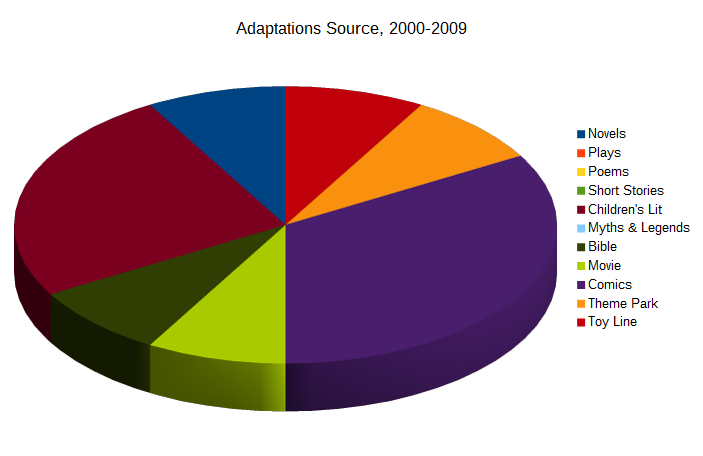

If the Eighties and Nineties were the exception, then why the complaints? The next few graphs might shed some light. I chose three separate decades, the Early Years, the Fifties, and the Aughts, to show what sources were used for adaptations.

Novels and plays are the bulk of the adaptations. Neither take over half, but the literary tradition is there. The other three sources, poems, myths and legends, and the Bible, aren’t that much different. The era is literary.

In the Fifties, novels and plays are major sources in adaptations, but other works are appearing. The number of remakes equal the number of movies using plays as a source. Myths and legends have a larger piece of the pie than in the Early Years. Children’s literature is a new source, thanks to Disney, but poems are still being used.

With the Aughts, the literary sources drop. Novels and plays combined equal the number of movies based on children’s literature. Comic books are a bigger source. The Aughts also had movies based on sources not seen in the previous decades – toy lines and theme park rides.

The Aughts may be showing why there is a complaint about the number of adaptations. The source work is far better known today. A movie based on one of Shakespeare’s plays passes the acceptance test. A movie based on a line of action figures is being made because either the toy line is selling well or the toy company wants to sell more of the toys, and thus can irk people. The same holds with using children’s literature and Young Adult works; there’s a feeling of catering to a younger audience that alienates older viewers.

Adaptations aren’t a new phenomenon. They’ve been around since the beginning of the film industry and will be around until the industry collapses. Film making is expensive. Studios need to pull in an audience, and, if done well, adaptations of popular works will draw in the crowd.

The History of Adaptations

Twenties

Thirties

Forties

Fifties

Sixties

Seventies

Eighties

Nineties

Aughts

Welcome to the history of adaptations. I’ve been looking at the top movies of each decade, analysing them to see which ones were original and which ones were adaptations, and of the adaptations, what the source material was. I’m using the compiled list at Filmsite.org as a base. Last time, the Aughts had fewer original movies than the Fifties, which had three, including the two Cinerama demo films.

The decade isn’t over yet, but the general trend has been for big budget adaptations based on comic books and Young Adult novels, or so it feels. Does this feeling hold out when looking at the popular movies so far this decade? Both Marvel and DC have a number of movies scheduled over the next few years, with Valiant getting in on the action. Movies adapted from Young Adult novels soared with the later Harry Potter films and the Twilight adaptations. Sustainability is in doubt, but the studios are making too much money to ignore the cash cow.

The top movies of the decade, by year, up to 2015:

2010

Toy Story 3 – sequel. Pixar’s approach to storytelling means that they won’t create a sequel unless there is a proper story to be told.

Alice in Wonderland – adapted from the 1872 Lewis Carroll story, Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There.

Iron Man 2 – sequel of an adaptation and part of the lead up to Marvel’s The Avengers.

2011

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 2 – both an adaptation and a sequel. The movie covers the latter half of the last book of JK Rowling’s Harry Potter series.

Transformers: Dark of the Moon – sequel of an adaptation of the Hasbro toy line.

2012

Marvel’s The Avengers – adaptation of the Marvel superhero team.

The Dark Knight Rises – sequel of the adaptation, The Dark Knight.

The Hunger Games – adaptation of the novel, The Hunger Games, by Suzanne Collins.

2013

The Hunger Games: Catching Fire – sequel and adaptations of the second book in the Hunger Games series by Suzanne Collins, Catching Fire.

Iron Man 3 – sequel of an adaptation.

Frozen – adaptation of the fairy tale, “The Snow Queen”, by Hans Christian Andersen.

Despicable Me 2 – sequel. The first movie, Despicable Me was an original work.

2014

American Sniper – adaptation of American Sniper: The Autobiography of the Most Lethal Sniper in U.S. Military History by Chris Pyle

Guardians of the Galaxy – adaptation of the characters and team as seen in Marvel comics.

2015

Jurassic World – adaptation. While intended as a sequel to the first three Jurassic Park movies, there are only two returning characters, including the island.

Avengers: Age of Ultron – sequel to the adaptations, Marvel’s The Avengers.

Inside Out – original but inspired by the daughter of the director

Furious 7 – sequel and part of the Fast and Furious franchise.

Of the eighteen movies listed above, four are original, including the sequels Toy Story 3, Despicable Me 2, and Furious 7. There are nine adaptations, including both Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 2 and The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, which are also sequels. The remaining five films are sequels of earlier adaptations. Naturally, the divisions weren’t easy to define. Jurassic World could be seen as a sequel of the previous Jurassic Park movies. I placed it as an adaptation because of how little it shared with the previous films. While Universal Studios counts the film as part of the Jurassic Park franchise, Jurassic World only has one character returning, and he was a minor one in the original movie. Thus, I’m placing Jurassic World into the adaptation category.

The source of the adaptations isn’t as diverse as the Aughts. Six movies were adaptations of comic books. Three were based on Young Adult novels. One came from a Michael Crichton work. Disney was the only studio to reach into the literature of the past for adaptations, using works by Lewis Carroll and Hans Christian Andersen. While comics haven’t had this strong a showing in previous decades, they aren’t a new medium. The Avengers #1 was published in 1963, bringing together characters from other titles, including Iron Man, who first appeared in Tales of Suspense #39 in 19591963*. Jurassic Park, published in 1990, is more recent.

Along with the above breakdown, there were ten sequels in the popular list. While Lost in Translation treats sequels as original works, continuing a story started in a previous film, the general movie audience may not agree with the assessment. The number of sequels, adaptations, and the combination of the two leads to the complaints that there are fewer original works. Yet, the Aughts had fewer popular original movies than this decade.

Next week, wrapping up the series.

* I misread the information at the link. Iron Man’s debut was in 1963; Tales of Suspense started in 1959.

The History of Adaptations

Twenties

Thirties

Forties

Fifties

Sixties

Seventies

Eighties

Nineties

Welcome to the history of adaptations. I’ve been looking at the top movies of each decade, analysing them to see which ones were original and which ones were adaptations, and of the adaptations, what the source material was. I’m using the compiled list at Filmsite.org as a base. Last time, the Nineties saw a slight slippage of the originality of the Eighties, but original works still outnumbered adaptations.

If the early days of AOL and the creation of the World Wide Web* allowed people to discuss films indepth, the normalization of the Internet meant that word of mouth could make or break a movie. A movie featuring two hot actors – Jennifer Lopez and Ben Affleck, linked via tabloids as “Bennifer” – should have had a good opening weekend. Instead, Gigli bombed at the box office as word of mouth sent warnings to avoid the film. Gigli set a record in 2003 for the biggest drop between opening and second weekend box office totals.**

I used “Weird Al” Yankovic as a barometer of popularity in the Eighties and Nineties. In the Aughts, he only had one song, “Ode to a Superhero“, released on the first album after Spider-Man hit theatres. His focus turned to the Internet, where popular memes now start. That change of focus is emblematic of how far into daily lives the Internet has become. Movies aren’t the trendsetters as they were in early days of Technicolor.

The top movies of the decade, by year:

2000

How the Grinch Stole Christmas – live-action adaptation of the Christmas story by Dr. Seuss.

2001

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone – adaptation of the popular children’s novel by JK Rowling. Harry Potter was a huge phenomenon, with people lining up outside bookstores when the new installments were released, something seen in the past for concert tickets for the biggest of the big name rock stars and with geek-friendly movies.

2002

Spider-Man – adaptation of the Marvel character seen in Spectacular Spider-Man and The Amazing Spider-Man.

2003

Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King – adaptation of the third book of JRR Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, The Return of the King. Also counts as a sequel.

2004

Shrek 2 – sequel of an adaptation. The first Shrek movies was based on the 1990 children’s book, Shrek!, by William Steig.

Spider-Man 2 – sequel to the 2002 adaptation, Spider-Man, above.

The Passion of the Christ – Mel Gibson’s controversial Biblical adaptation of the last days of Christ.

2005

Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith – the last of the Star Wars prequel movies.

2006

Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest – adapted from the Disneyland ride, “Pirates of the Caribbean”.

2007

Spider-Man 3 – like Spider-Man 2, a sequel of an adaptation.

2008

The Dark Knight – adaptation of the DC Comics character, Batman, as seen in a number of titles, including Legends of the Dark Knight and Detective Comics

2009

Avatar – original. James Cameron created an immersive world using 3D filming techniques, reviving the film process.

Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen – sequel of an adaptation of the Hasbro toy line, Transformers.

That makes a grand total of one original movie, Avatar. Of the remain films, there were six adaptations, five sequels to adaptations, and one movie, Return of the King, that counts as both sequel and adaptation. The obvious question, “What is the difference between a “sequel of an adaptation” and “a sequel and an adaptation”? The answer – source material. Return of the King was still based on an existing work, in this case, Tolkien’s novel. The movie relied heavily on the original work, which itself was a continuation of a story started in a previous novel. With the Spider-Man sequels and Shrek 2, the movies built on the previous movie but wasn’t necessarily based on the original work. The distinction is academic, but it does exist and will come up again.

The sources of the adaptations is another difference from previous decades. Literature and plays were the prime sources up to the Eighties. In the Aughts, three movies were based on children’s literature, with only one being animated. In the past, it was typically an animated Disney film that covered children’s books. Four movies were based on comic book characters, though three of those films featured Spider-Man. The Bible returned as a source, the first time since 1966’s The Bible: In the Beginning. Rounding out the literary sources is The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien’s fantasy epic.

What makes the Aughts unique is the use of unusual original sources, a toy line and a park ride. In the Eighties, Hasbro took advantage of a relaxing in regulations governing children’s programming, allowing them to work with Marvel and Sunbow to produce cartoons for several lines of toys, including Transformers, G.I. Joe, and Jem and the Holograms. Of those three mentioned, Transformers kept returning to television in one form or another, with little continuity between series***. With the animated series being a near constant, a live-action movie version wasn’t a surprise. The park ride, on the other hand, is Disney leveraging one of their existing properties in another field. The Pirates of the Caribbean wasn’t the only ride turned into a feature film. The Country Bears, The Haunted Mansion, and the recent Tomorrowland all began as Disney rides.

With just one more decade to go, it’s easy to see where complaints about Hollywood’s lack of originality comes from. After two decades where original works were in the majority, even taking into account sequels, the sudden turn around back to the level last seen in the Fifties makes the Aughts seem abnormal. As seen in this series, The Aughts and, as shall be seen, the New Teens arent’t unusual. The Eighties and Nineties were the exceptions, but since they are within recent collective memory while the earlier years are outside the pop consciousness, it’s difficult to realize how unique those decades are in the history of film. The Aughts also pull from sources not previously used as extensively. Prior to the Eighties, only animated films meant for children used children’s novels as a source. The Harry Potter phenomenon changed how people see children’s literature and opened the doors for movies based on Young Adult novels.

* Best cat photo distribution method ever created.

** The record has since been broken, first in 2005 by Undiscovered and then in 2007 by Slow Burn.

*** I’m simplifying this a lot. Transformers continuity is flexible and depends on the writer. Oddly, Beast Wars/Beasties is in continuity with the original Transformers cartoon despite the differences in time and in animation styles.

NBC has announced a remake of the Eighties series, Hart to Hart, with a twist. The original, airing from 1979 to 1984, starred Robert Wagner and Stefanie Powers as Jonathan and Jennifer Hart, a rich married couple whose hobby was fighting crime. Lionel Stander co-starred as the Harts’ butler and chauffeur. The twist? The new Hart to Hart will be a gay couple, Jonathan Hart and Dan Hartman*, a by-the-book attorney and a free-wheeling journalist, who fight crime.

With just the announcement, there’s some notable differences already. First, the new series has crime fighting part of the couple’s day job. In the original, as I mentioned, it was more a hobby or a side effect of their careers and wealth. The original Harts were independently wealthy, letting them go to wherever needed because they owned their own jet. Hart and Hartman may not have the mobility, but they will have more exposure to local crimes because of their jobs. Second, the wealth factor. Jonathan and Jennifer were rich. Jonathan and Dan should be comfortable enough to purchase or at least expense items, but unless either come from a wealthy family, there’s no butler. For the third difference, the obvious elephant in the room, Hart and Hartman are gay. Really, that shouldn’t be a problem, but with Kim Davis in the news the past few weeks, count on people complaining that there are gays on their TV.

The question, though, is why remake Hart to Hart instead of creating a new series?

Pros

Name recognition. Hart to Hart still rings a bell for the older audience and has a good ring to it. The name should pull in viewers who are curious.

Age. The last first-run episode aired over thirty years ago. The series is old enough and and has been off the air long enough that intimate familiarity is lacking. Hart to Hart also doesn’t have the same level of syndication as any of the Star Trek series. This lack of familiarity will let writers focus on the new characters without necessarily causing moments of, “But that’s not what Jonathan would do!”

What a twist! With same-sex marriage a huge topic over the past few years, coupled with the US Supreme Court overturning state level bans against those marriages, the series gains a new level of freshness. The younger audience, the people who poll very favourable to same-sex marriage, will appreciate the approach.

Cons

In name only. There are a number of key changes to the premise, as mentioned above. Changing the couple from opposite- to same-sex isn’t a problem, removing the wealth and thus one of TV’s better supporting role is. Again, if one of the pair is wealthy, the butler can remain, but nothing in the article mentioned anything about wealth. There is also nothing said about whether Hart and Hartman are married, though I have thoughts to share below about that.

It’s not its own work. This is the flip side of name recognition, above. The series can become a mainstream hit, showing a couple working together, living together, fighting crime, with the only difference being that they’re both men. But it’ll be known as a remake. Shouldn’t a ground breaking show be its own thing?

A few things I’d do with the show, which may or may not be planned already include working in the marriage and making sure the characters feel real instead of stereotypes. With the marriage, have it as a subplot through the first season. Hart and Hartman keep trying to get the wedding planned, but they keep getting sidetracked by investigations. Jonathan and Jennifer were an established married couple, having a few years of wedded bliss behind them; Jonathan and Dan don’t have that luxury because of legalities**. Given my druthers, I’d change Jonathan Hart to John Soul and change the title to Hartman & Soul, but I don’t work for a network.

If the show is successful, this could open up some older series to be remade with gay couples. Picture Simon & Simon*** remade, with the brothers turned into a gay couple who are private investigators; or McMillan and Wife as a lesbian couple, one being the commissioner of the San Francisco Police Department.

Jokes aside, I do hope the series does well, assuming it makes it to air. Quality work needs to be encouraged.

* Er, so shound’t the series really be called Hart to Hartman?

** Depending on the state. Set the series in California, and they could have been married since 2008.

*** If the Internet was around like today when Simon & Simon aired, the amount of Simcest fanfics would overwhelm the Supernatural Wincest fics.