Mighty Morphin Power Rangers‘s history starts in Japan. Toei, developed Sentai, a series about masked heroes fighting monsters, in the Sixties. After a deal with Marvel to bring over some of the comic company’s heroes resulted in mecha getting added to sentai series, Toei continued to add giant robots, creating Super Sentai. The sixteenth series, Kyōryū Sentai Zyuranger, caught the attention of Haim Saban, owner of Saban Entertainment. Saban worked out a deal to get the footage from Zyuranger to which he’d use the action scene and create new stories to go with them. Mighty Morphin Power Rangers debuted in 1993.

The original Power Rangers, Jason Lee Scott, Kimberly Hart, Zack Taylor, Trini Kwan and Billy Cranston, were recruited after the sage Zordon ordered his robot aide, Alpha 5, to find “five teenagers with attitude.” Zordon needed a team to stop Rita Repulsa, an alien sorceress who escaped imprisonment after 10 000 years. To help fight Rita and her monsters, the Rangers received Zords, mecha that can combine into the MegaZord. The Rangers defeat Rita’s monsters regularly, but the sorceress has a new plan – defeat the Rangers with one of their own. She kidnaps the Green Ranger, Tommy Oliver, and turns him against the others. Tommy does break free of the brainwashing and aids the others against her. The series sold a number of toys, from action figures to Zords. The effects at times were weak, the result of being a weekly series in Japan. However, the series had a following. The franchise is now in its twenty-fourth season with Power Rangers Ninja Steel.

As is the way of Hollywood, a popular TV series will be adapted. Despite being in its twenty-fourth season, the studio went back to the beginning, Mighty Morphin Power Rangers. There is a tendency for film makers to turn a children’s series darker and grittier to the point where the feel is off. With a series featuring martial arts, the potential for a grimdark remake existed. Instead, the movie took a different approach, acting as an origin for the Rangers.

The movie starts at the beginning of the Cenozoic Era with a battle going badly for the Power Rangers. Red Ranger Zordon, played by Bryan Cranston, orders Alpha 5, voiced by Bill Hadar, to send a meteor on his position. This desperate act of self-sacrifice is to protect the Earth’s Zeo Crystal and the Rangers’ Power Coins from Rita Repulsa, played by Elizabeth Banks. The meteor wipes out the dinosaurs, and buries not only the Zeo Crystal and the Power Coins, but sends Rita deep into the ocean.

Millions of years later, Jason Scott, played by Dacre Montgomery, makes a bad decision in trying to steal a mascot and winds up injuring his leg, destroying a potential career in football, placed under house arrest, and sent to detention. While serving detention, he meets Billy Cranston, played by RJ Cyler, and Kimberly Hart, played by Naomi Scott. Billy is in detention for blowing up his lunch box. Kimberly is there because she forwarded an image of her cheerleader friend throughout school. Jason becomes Billy’s friend after stopping a bully from tormenting him, though the feeling isn’t immediately reciprocated. Billy is a genius with electronics and is able to fool the tracker Jason wears as part of his house arrest.

In return for the help, Jason drives Billy up to a gold mine. Billy’s father had been trying to locate something hidden at the mine, and Billy continued the search after his death. He sets up the explosives and detonates them, getting the attention of Kimberly and two other classmates, Trini Kwan, played by Becky G, and Zach Taylor, played by Ludi Lin, are also at the mine and are drawn to the explosion. While Jason, Kimberly, Trini, and Zach argue about why they are all at the mine, Billy realizes that the rock wall is collapsing. The collapse reveals five unusual rocks, red, blue, pink, yellow, and black. Each of the teens grabs one and, with sirens approaching, runs away. Eventually, they all make it into Billy’s van. Jason tries to out run a train to escape both mine security and the police.

Out on the ocean, a fishing boat drags in its last haul of the day. Within the net of fish is the body of a woman. The boat’s skipper calls in for the police to meet the boat at the docks. The body isn’t quite so dead, though. Rita survived, frozen in the ocean until pulled on board. When one of Angel Grove’s finest arrives to investigate, he is surprised that the body not only isn’t dead but is trying to kill him.

Jason wakes up the next morning surprised to be alive and unsure of just how he got home. He gets out of bed, then notices that he isn’t wearing his knee brace. The red stone he discovered at the mine is still with him, even if he leaves it in another room. Jason also discovers that he has superhuman strength. He returns to the mine, where he sees the wreckage of Billy’s van. The other teenagers have also returned. More or less as a group, they explore the mine and discover a long buried spaceship deep under the rock. The ship’s caretaker, Alpha 5, rounds up the group and brings them to the central chamber to meet Zordon, who is now part of the ship’s computer matrix. Zordon welcomes the new Power Rangers and warns them that Rita will be at full strength again in eleven days. The new Rangers need to train and to learn to morph.

While their training, while painful, is difficult, the new Rangers do learn. Alpha 5 presents holographic versions of Rita’s Putties, the minions she uses as the first wave. Morphing, though, is another matter. None of the Rangers are able to morph at first. Even after Alpha 5 shows the Rangers their Zords, mecha that took the shape of the dominant life form of the Cenozoic Era, the teens aren’t able to morph. The closest any of them get is Billy, who morphs into his blue armour while breaking up a fight between Jason and Zack.

Rita keeps busy while the Rangers train. She collects gold to recreate her monster Goldar, who will be able to dig to retrieve Earth’s Zeo Crystal, dooming the world and giving her the ability to destroy other planets. Rita isn’t picky about where she gets her gold, either. Some of her victims have their gold fillings removed. She senses the other Power Coins and realizes that new Rangers have been discovered, in part because she had been the Green Ranger under Zordon’s leadership until she turned her back on her oath. Rita breaks into Trini’s home to have her send a message to the others to be at the docks.

Trini tells her fellow Rangers about Rita. Despite not being able to morph yet, Jason decides that this is the best time for them to take down Rita. Rita, though, is more than ready for them and easily defeats the group. She knows one of them has the location of the Zeo Crystal and threatens to kill the Rangers one by one until she gets it. Billy, who managed to work out where the Crystal is, doesn’t want to lose any of his new friends and gives her the key words without completely giving away the location.

It takes a tragedy to turn the Rangers from a group of teenagers into a proper team. The death of a teammate makes them realize that each of them would gladly sacrifice their life for the others. The Morphing Grid unlocks and instead of Zordon returning, the dead teammate does. The team morphs for the first time and heads out to fight Rita once again. Rita, though, sends her Putties against them at the ship. The fight is difficult, but when Zach brings out his Zord to even the odds, the others follow suit. The Putties defeated, the Rangers ride out to save Angel Grove from Rita and her monster.

Unlike the TV series, the movie has the advantage of being written as one whole instead of having to incorporate existing footage from Zyuranger with a new script. The formular of the series – Rita hatches a scheme, sends out her Putties and her monster of the week, Putties get defeated, monster forces the Rangers to call their Zords, Rita makes her monster grow, and the Rangers summon the MegaZord – is in the movie, but the movie isn’t just the formula. Instead, the formula provides a scaffold to build on, and gets reshaped in the process. The heart of the movie is the team and how the Rangers come together.

Each Ranger has a problem to overcome. Jason’s is that he is impulsive and prone to self-sabotage. Kimberly was a mean girl who had to face up to what she did. Zach is worried about his mother and being alone if anything happens to her. Trini is discovering that she is a lesbian and feels that she’s an outsider even in her own family. Billy is on the autistic spectrum and is well aware of the problems he faces as a result. By being able to move past their problems and open up to each other, they turn from a group of teenagers to a team of Power Rangers. Each of the Rangers’ problems comes from a real place. None of them are sensationalized. Billy’s autism is one of the more realistic portrayals around, as is Trini’s feeling of being an outsider because of her sexuality and Kimberly’s reaction to what she had done to her friend.

The casting worked. As mentioned above, RJ Cyler’s portrayal of Billy was believable. Elizabeth Banks as Rita channelled J-horror movies, with her early movement similar Ringu`s Sadako. Rita went from evil sorceress to frightening villain. Bryan Cranston’s Zordon had wisdom fighting against desire, a mentor who demanded much but knew exactly what the stakes were. The movie also used colour as a symbol. When the Rangers first meet and while they`re still trying to morph, the colours are muted, dark, and murky. When they become a team, the colour turns bright and full. In part, this helps show off the Zords and the Rangers colour-coded armour, but it also works to show the transition from teenager to hero.

Power Rangers takes Mighty Morphin Power Rangers and expands on it, giving the Rangers depth of character and showing them becoming heroes. Rita’s villainy also expands, showing just how evil the sorceress is. Yet, the movie never forgets its heritage and embraces it. Power Rangers is a well-done adaptation of a beloved franchise’s beginnings.

Lost in Translation is taking this week off but will return next week. You can also follow Lost in Translation over at Facebook.

Spunky girl detectives can be traced back to one source – Nancy Drew. The character first appeared in 1930 with the publication of The Secret of the Old Clock, sending the titian-haired sleuth into fame. The original Nancy Drew Mystery Stories series ran for 175 books from 1930 until 2003, with more books under new series since then, along with a series of video games from Her Interactive.

Nancy plies her trade as an amateur sleuth in the fictional town of River Heights, where she lives with her lawyer father, Carson Drew, and their housekeeper, Hannah Gruen. Nancy’s mother died long before her adventures started, leaving Hannah in the role of a surrogate mother. Carson’s work leaves him away from home for extended periods, giving Nancy a sense of independence that allows her to investigate. However, Nancy isn’t alone. She has her cousins, the feminine Bess Marvin and the tomboy George Fayne, and her beau, Ned Nickerson, along to help her. Nancy is self-sufficient, capable of not only getting into trouble but getting herself out on her own.

Behind the scenes, the Nancy Drew Mystery Stories was created as the distaff side for the Hardy Boys for the Stratemeyer Syndicate. Ghostwriters using the pen name Carolyn Keene wrote the stories based on plot outlines created by Edward Stratemeyer and his daughters. The early years saw new books published four times a year; these releases were always anticipated and sold well.

With a long history, Nancy inevitably would wind up on the silver screen. Warner Bros. released a series of four movies in 1938 and 1939. Nancy has also appeared on television, with a series in 1977 starring Pamela Sue Martin. Hollywood is attracted to popular characters, and Nancy Drew has maintained her popularity over the years since her first appearance.

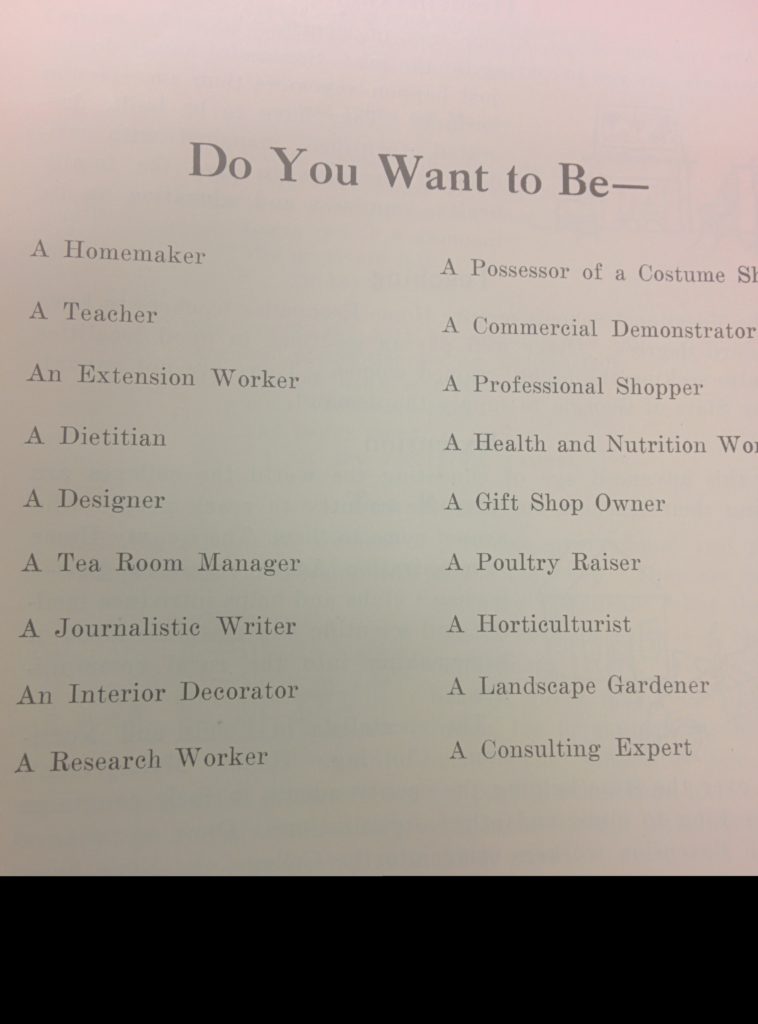

With such a long history, adapting the character poses some problems. The biggest is the changes in culture since 1930. The racism of the Thirties just does not fly today. The expectations of young women have changed. No longer are teenaged girls expected to go to college to get degrees in Home Economics; instead, women are breaking through barriers in all walks of life. An adaptation would have to work out how to balance what is acceptable in entertainment today while still keeping the core of the character.

Welcome to a woman’s destiny in 1924, via the Georgia State College of Agriculture bulletin, “What Women Can Do”.

With this in mind, it’s time to look at the 2007 adaptation by Warner Bros, simply titled Nancy Drew. The movie starred Emma Roberts as the titian haired sleuth, with Tate Donovan as Carson Drew and Max Theriot as Ned Nickerson. The story starts in River Heights at the tail end of one of Nancy’s cases, inside a church as she talks a pair of crooks into surrendering to the police after they caught her. The commotion, though not only draws out the town to root for Nancy but also brings Carson out from work, which happened to be in court at the time. As a result, Carson gets Nancy to promise to no sleuthing while they are in Los Angeles.

However, Carson forgot that Nancy arranged for the housing arrangements in LA. She found a haunted mansion once owned by the famed actress Delilah Dreycott, who disappeared in mysterious circumstances twenty-five years prior. The mystery draws Nancy in, despite her promise to her father to not sleuth. What should be a simple investigation, though, leads to threatening phone calls and the discovery of Delilah’s illegitimate daughter, Jane Brighton, played by Rachel Leigh Cook. After meeting Jane, Nancy changes the direction of her investigation into finding the late actress’s will to help Jane and her daughter. As expected, Nancy does get kidnapped after finding the will, but she escapes on her own, and is able to reveal the mastermind behind the plot.

Emma Roberts as Nancy was able to carry the movie on her own, portraying the girl detective as competent and capable. While her classmates in LA made fun of Nancy’s fashion choices, the look was based on illustrations in the books, updated for today. Outside Los Angeles, Nancy wouldn’t look too out of place, eccentric but not decades out of date. The movie’s story was original but used elements from the books, including Nancy’s penchant for getting captured by the villain’s henchmen and for escaping. The movie also showed Nancy as a capable young woman, independent but still her father’s daughter. Just as important, Nancy’s hair was titian, not blonde nor brunette.

The movie also tossed in a few Easter eggs for fans. Several of Delilah’s old films took their names from the Nancy Drew Mystery Stories, including Mystery of the Lilac Inn. Nancy had a blue ragtop roadster, a Nash Metropolitan, the same colour as it had in the books. Bess and George made quick appearances at the beginning of the movie while it was still in River Heights, and it was possible to tell the cousins apart just by their clothes. Ned appears both at the beginning and comes back in the middle of the movie with the roadster.

While the movie wasn’t based on any one book in any of the various Nancy Drew series, it was based on an amalgamation of Nancys through the years, updating her while still keeping her true to her nature. Nancy Drew was aimed at the same audience that the books are, but made sure that the clues were there to be seen by viewers as well as Nancy herself. The result is a work that takes pains to bring a character up to date without losing what made her so popular in the first place.

After a few weeks of heavy works, it’s time to take a small breather. To celebrate the recently passed Ides of March, it’s a good time to look at the classic Wayne & Shuster sketch, “Rinse the Blood Off My Toga“.

The death of Julius Caesar at the hands of Roman senators led by Brutus became fodder for William Shakespeare, who turned the assassination into a tragedy. The play, Julius Caesar, was first performed in 1599 and has been a regular in the repertoire of many a Shakespearean company. Julius Caesar is also a common play taught in high school English classes, thus continuing the legacy of those fateful Ides of March.

Meanwhile, Johnny Wayne and Frank Shuster* created their duo, Wayne & Shuster, after working together since high school. They went professional in 1941 on radio with CFRB in Toronto. “Rinse the Blood Off My Toga” was released on LP in 1954, and was then used for their big break with American audiences on The Ed Sullivan Show. After the show, New York City bars were offering “martinus specials” after a line from the act**. Sullivan had the duo back a record sixty-six more times over eleven years.

“Rinse the Blood Off My Toga” is a hard-boiled detective story using Julius Caesar as the starting point. The obvious place to start is after the big murder, the assassination of Caesar. Wayne’s character, Flavius Maximus, is a private Roman eye, hired by Shuster’s Brutus to find who killed Caesar. As Brutus, Shuster is giving a wink and a nod to the role the character had in the play. The sketch plays out as advertised, a hard-boiled detective story, with the various suspects coming up and being interrogated, including Calpurnia, Julius’ wife. The play’s characters are treated as if they had Mob connections as Flavius looks for Mr. Big.

As a comedy sketch, “Rinse the Blood Off My Toga” toys with the source material, going for laughs instead of accuracy. Yet, the sketch does show another way to adapt a work, by taking a different angle, either through the eyes of a minor character on the edge of the events or by bringing in a new character as an observer. Flavius Maximus wasn’t in the original Julius Caesar, but the mixing of genres allows him to insert himself into the aftermath of the assassination and bring Brutus to justice.

* Frank Shuster’s cousin Joe also became famous, through Superman. His son-in-law, Lorne Michaels, also is famous, having created Saturday Night Live.

** Flavius: “I’d like a martinus.”

Cicero: “Don’t you mean a martini?”

Flavius: “If I want two, I’ll ask for them.”

Last week’s look at Mercury Theater’s War of the Worlds saw HG Wells’ science fiction story about the invasion of Britain by Martian war tripods moved wholesale to New Jersey. The radio drama is a classic presentation; yet, localization is becoming problematic today, with concerns about live action version of both Ghost in the Shell and Akira around. Today’s post will look at the issues around localizations.

A localization is an adaptation remade for a new audience, taking into account what the culture that the audience lives in. An localization made for an American audience is better known as an Americanization. Several popular television series came about because of Americanization, including All in the Family, after the UK series Till Death Do Us Part; Three’s Company, after the UK series Man About the House, and The Office, after the UK series of the same name. Not every attempt to Americanize a foreign work succeeds, though. The nigh-infamous clip of Saban’s Sailor Moon missed the core of what the original was about in an attempt to bring the anime across the ocean.

The difference between Mercury Theater’s adaptation of The War of the Worlds and Saban’s failed Sailor Moon adaptation lies in the intent. Mercury Theater’s goal was to scare New York City; bringing over the Martian invasion from the British countryside to New Jersey, across the river from the Big Apple. The biggest changes to the story were location and time, with a focus that changed from a first-person narrative to eyewitness news reports on the radio. To the end Mercury Theater wanted, the action had to be close to the listeners. An invasion of Britain would not have had the immediate impact that destroying Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, had.

With Saban’s Sailor Moon, the intent was to bring in a popular anime series without necessarily bringing the aninme. The new series was part live action, part animated, with a superficial resemblance to the original. However, the core of the original Sailor Moon was, ultimately, the concept of a shoujo heroine in Japanese fiction. Usagi is the least likely person to ever save the world multiple times. She’s not the smartest, not the strongest, and not the bravest, but she has heart. Her heart is how she defeats villain after villain. Sailor Moon wins not because she’s the most powerful, but because she believes in her friends and is willing to extend a hand in friendship. Usagi is the hero, not Sailor Moon, and that’s a concept that can get easily lost in translation.

Note that both adaptations have a target audience. Even Saban’s attempt at localizing /Sailor Moon/ was based on the company’s knowledge of American children’s television. Likewise, the three TV series mentioned at the beginning were well aware of the audience that would be watching. Norman Lear, creator of All in the Family, had seen episodes of Till Death Do Us Part and was struck by how much the relationship portrayed there resembled the one he had with his father. All in the Family was built upon that resemblance, allowing a near-universal experience be the core. The American version of The Office reflected the American work experience, which, because of differences in labour laws between the US and the UK, results in a different dynamic.

Television has the luxury of being able to target a specific audience. The bulk of the television work out of Hollywood is meant for American consumption, with foreign markets a bonus. Movies, though, don’t have that option. With budgets rising and frequently break the $200 million mark, studios can’t rely on the domestic take to break even. Films on the big screen need to have a broader appeal today. A work that is known internationally is a draw studios want, but too many try to Americanize to appease the domestic market. Some of these works, though, don’t translate well. Ganriki.org has gone into details about the problems surrounding the live action Akira movie, from the screenplay to the purpose of the movie. Essentially, the US was never the target of the only two atomic weapons used in war, and never had to rebuild after a defeat, something that is inseparable from Akira.

Moving away from anime, Harry Potter was spared from localization thanks to JK Rowling being able to set terms, and that was from the sheer popularity of the books. Like Akira, Harry Potter is very much set in the country of its origin. Britain has a long history, with castles that are older than current North American nations. Boarding schools are common enough that the average person in the UK will have a good idea of what being at one is like. The wizarding world in the books is as old as the country. Moving Hogwarts to the US loses the sense of foreboding history that the school has in the books. The characters reflect British society throughout time, from the upper class Malfoys to the common Weasleys. Harry Potter also demonstrates the power of the draw. Audiences wanted the Harry they read about, not one that was transplanted to another country. With works that have the widespread appeal like Harry Potter, alienating the audience is not a good idea.

Similar to the problems facing Akira and a hypothetical American Harry Potter, the 1998 Godzilla lost some important elements on moving the action to New York City. While Tokyo and NYC are major cities along a coast, filled with tall buildings, a lot of people, and neon, the similarities end there. The first American Godzilla movie forgot that the eponymous monster was a result of the nuclear age, going back to the two atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, followed by the nuclear weapon tests in the Pacific. It is possible to have a story featuring giant monsters stomping through an American city, but Godzilla has cultural ties that don’t make the journey to the West easily. The 2014 Godzilla acknowledges the nature of the monster’s origin, starting him near Japan before sending him westward.

What can help with localization is changing the nature of the story. War of the Worlds updated the story; the American military, with its mechanization, its improved communications, its aerial capabilities, all not available in 1897, still lost to the Martian invaders. The Seven Samurai, a story based in Japanese samurai, was successfully translated to the American West with The Magnficent Seven and then moved into science fiction with Battle Beyond the Stars. The goal in these adaptations wasn’t so much to localize, but to retell the story within the new trappings. Ronin became guns-for-hire, who then became starfaring mercenaries; all three are similar, but are very much dependent on their culture and their settings. Similarly, Phantom of the Paradise took the core ideas from both Faust and The Phantom of the Opera and combined the stories and bringing them into the Seventies, with a villainous record producer in the role of Faust and a hapless songwriter as the Phantom.

Sometimes, though, the effort to localize doesn’t pay off. The film version of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo kept the story in Sweden. The plot could have easily been moved to an American setting, yet the makers kept the work in Sweden, with most of the cast being Swedish. Part of the decision comes from the original work; the novel is set in Sweden, using various towns in the country. Moving the work would mean finding a similar location, It was easier to keep the Swedish locations.

Localization isn’t necessarily a negative. Presenting a story that the intended audience can understand culturally can get the point of the story across. The problems begin when the original’s culture isn’t accounted for when translating the work. Care needs to be taken, and there are some works that don’t translate well, even if the two countries involved share a common language.

This week’s subject, The Mercury Theater presentation of HG Wells’ War of the Worlds demonstrates two elements that have recurred here at Lost in Translation. The first is the medium of the adaptation and how time available affects how the original is adapted. The second is the passage of time and how it affects an adaptation made decades after the original.

As has been mentioned in a number of previous Lost in Translation entries, the time allotted for a work has a direct impact on how the adaptation is handled. Long form works, such as novels and television series, allow for a deeper examination of characters and events. Shorter works, including movies, need to get to the point straight away. Details get lost or bundled together, whether character or setting. Even films trying to be as faithful as possible to an original work will have to lose details just to keep to a reasonable running time.

The passage of time and the advances in technology can affect how a work is seen. Unless the adaptation is treating the original as a period piece, the changes in available technology can cause problems. This typically happens when an original work is set in “now”, whenever that “now” was. For example, “modern” works from the Eighties often show characters using car phones, large blocky handsets plugged into the vehicle’s cigarette lighter port. If the work were to be brought to the today of the 2010s, that blocky car phone would be replaced with a smartphone with far better coverage and no need to go through a mobile operator, which may reduce the tension in a scene.

Wells’ War of the Worlds was first published in 1897 as a serial, and told from a first-person perspective as a journal by the narrator. The story details the Martian invasion of Earth, starting from the first impact of a Martian cylinder in the English countryside. The locals are abuzz, wondering what the object is. After the Martian recovers from its journey and landing, it begins to use a terrible weapon, a heat ray, against the crowds. The Army is sent in, with cavalry and horse-drawn artillery, to deal with the threat; but with more cylinders falling, each one containing a Martian war tripod, the soldiers stood no chance.

The narrator tells of his journeys and the people he meets during the initial attack and the response. News travels by word of mouth, mainly from the narrator as he walks through the countryside to reuinite with his wife and escape the destruction. The Army, though, uses heliographs to maintain communications between units. London is unaware of the danger despite news reports trickling out until the tripods reach the city three days after landing. The Martians have a second weapon, a black smoke that kills anything that breathes it. British civilization begins to break down as the Martians march unimpeded. The mighty British Empire is brought to its knees. The only thing that saved the Empire and the world was microbes, bacteria that humanity had a resistance to that the Martians did not.

The 1890s saw the British Empire at its height, with the sun never setting on it. The Industrial Revolution fifty years prior brought along mechanization, allowing for steam engines, railways, and ironclad ships. Tensions between empires existed, with the expectation that one or another would try to invade Britain. With War of the Worlds, Wells introduced an invader that was more than a match for the British military forces.

In 1938, much had changed. The horse-and-carriage gave way to the automobile and radio allowed for faster transmission of news to listeners. The Great War brought down several empires and introduced new forms of warfare. The threat of war with Nazi German loomed. Orson Welles and his Mercury Theater brought the 1897 story up to date in a sixty minute radio drama on October 30, 1938, the day before Hallowe’en.

The radio version of War of the Worlds made several changes. The setting was localized to the area near New York City. Scaring a large radio market is easier when using areas local to it than using English towns like Woking, home to HG Wells. The second was to accelerate the first book of the novel. Welles used the immediacy of radio to drive the first two-thirds of the drama, having events happen in almost real time. The show is interrupted by breaking news from Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, an alien cylinder crashing into a farmer’s field. The cylinder reveals itself as a hostile machine, firing a heat ray. The station then turned over its facilities to state militia to allow for better communications, allowing the audience to follow the action. The black smoke has a more immediate impact listening to an artillery battery succumbing to it. Another scene has an Air Force squadron trying an aerial attack against the tripods and being shot down by heat rays, something that Wells couldn’t have added as the Wright Brothers hadn’t yet made their first powered flight. And like London in the novel, New York City tries to evacuate.

The last third has Welles’ character, Professor Richard Pearson, formerly of the Princeton Observatory, wandering through the New Jersey countryside, meeting a number of people the same way Wells’ unnamed narrator had in the novel. Pearson is trapped at Grover’s Mill, the initial landing site of the invasion. His life has changed; time passes without being marked, and his primary goal has become survival. The survivalist Pearson meets is taken directly from the novel, with almost no changes except for time constraints.

HG Wells’ lone first-person narrator may work in a novel, allowing the reader to experience events through the character. Radio, though, loses that connection if someone narrates from that perspective. Instead, breaking news with no apparent filtering allows the listeners to bring their own emotions in. The invasion happens faster on radio than in the novel, but response times have also increased. Cavalry in 1938 means tanks and aircraft, not horses. Radio is far more immediate than even telegram. The listener’s response is more raw; the separation that exists between book and reader is reduced or even removed on radio, especially when the format used is a news broadcast. The most heartbreaking moment is a radio operator, call sign 2XQL, calling out, “Is there anyone on the air? Is there anyone on the air? Is there anyone?”

Mercury Theater’s adaptation demonstrates the elements that can be in the way when translating a work into a new medium. What works in one medium may not work in another. Wells’ lush paragraphs of description don’t translate into radio. Instead, the radio work has to build the setting through words and sounds. The heat ray’s effects, from the sound of it firing to the screams of its victims, were demonstrated. The discovery of the cylinder is treated as breaking news, broadcast, instead of being a curiosity for the townsfolk of Woking. However, despite the restrictions and the localization, the radio drama is a good adaptation, getting to the heart of the novel.

Before diving into the analysis, a note about nice round number in the title. Two hundred reviews. I never expected to get this far. The number doesn’t include all the non-review essays, including the History of Adaptations. Thank you all for reading and thanks to Steven Savage, who not only encouraged me to write about adaptations but also supplied web space, and to Paul Brian McCoy, of Psycho Drive-In for picking up the series and providing the visuals you see each week.

Television the past few seasons is taking the lead from the silver screen, with more adaptations appearing. Both DC and Marvel are well represented withy multiple series based on their titles. But comic books aren’t the only source being used. MacGuyver brings back the classic Richard Dean Anderson series, updated for today. Likewise, the Lethal Weapon TV series updates the original movies from the the late 80s to now.

The original Lethal Weapon, released in 1987, starred Mel Gibson as Martin Riggs and Danny Glover as Roger Murtaugh, and was a buddy cop action/comedy/thriller. Murtaugh is a family man, just turning fifty, counting the days until retirement. Riggs is a new transfer from Dover, suicidal since the death of his wife in a car collision. Being Christmas, Riggs’ depression has become far more severe, with his only reason to live being the job. The staff psychiatrist wants Riggs off the force as a danger, but the Captain believes he’s bucking for a disability pension. Riggs and Murtaugh get paired up as partners, then get assigned to a case that started as an apparent suicide. The victim appeared to get high and fell off a building, but the autopsy shows that the drugs were laced with drain cleaner.

As the investigation continues, Murtaugh realizes the truth about Riggs; he is suicidal, taking risks that could get him killed. Murtaugh invites Riggs to meet his family, who adopt him. As much as Riggs is suicidal, he is a family man, just one who lost his family. Seeing the Murtaughs at home and having them welcome him helps him, a little, enough for him to realize that there’s something else to live for.

The victim’s killer is part of a former CIA black operation from Viet Nam. A long shot lead that figiratively and literally explodes in their faces leads Riggs and Murtaugh to the ring. With the two detectives getting closer, the ring, led by former general McAllister, played by Mitchell Ryan, sends his people, including Joshua, played by Gary Busey, out to deal with them, kidnapping Murtaugh’s daughter Rianne, played by Traci Wolfe. McAllister underestimates just how crazy Riggs is, though, leading to the ring’s downfall.

The core of the film came from the strength of Shane Black’s writing, Richard Donner’s direction, and the chemistry between Gibson and Glover as Riggs and Murtaugh. As a pair of buddy cops, it takes them time to get to be buddies, as both have issues that they need to work through. Once they get to that point, they trust each other, though Murtaugh isn’t always sure of Riggs’ plans.

The success of Lethal Weapon meant sequels were going to happen. In 1989, Lethal Weapon 2 brought back Riggs and Murtaugh, adding in Joe Pesci as Leo Getz, a creative accountant and middleman under witness protection while waiting to testify. Guarding Leo means pulling Riggs and Murtaugh off their main case, an investigation into a drug ring headed by a South African* diplomat that leads to Riggs discovering that the accident that killed his wife wasn’t an accident. Lethal Weapon 3, released in 1992, brings back the trio and adds Rene Russo as Lorna Cole, an Internal Affairs investigator working a different side of a case involving the funneling of submachine guns and machine pistols with armour piercing bullets from police storage to the streets through a dirty ex-cop. Lethal Weapon 4, released in 1998, brings back everyone, with Riggs and Murtaugh promoted to Captain, skipping Lieutenant, because the LAPD’s insurance company won’t insure the force if the pair are still working the streets while a Chinese human trafficking ring, overseen by Jet Li as Wah Sing Ku. Throughout the series, the relationship between Riggs and Murtaugh grows, going from assigned partners to true friends.

The movie series was popular, with Lethal Weapon 4 showing the only dip in performance at the box office. Naturally, something popular will get remade. In the case of Lethal Weapon, it was remade as a FOX TV series starting in the 2017-2017 season. Television brings a number of new restrictions. Unlike movies, where ratings exist to help audiences decide what level of sex and violence they are comfortable with, television can’t go to such extremes. Each of the Lethal Weapon films were R-rated, mostly due to a level of violence that prime time television isn’t allowed to air. Adding to the ratings issue, television has a different timing compared to film. While a television episode may run forty-three minutes after removing ads, a season may run up to twenty-two episodes, giving the series time to expand ideas over multiple airings that a movie has to get in during its one two-hour show.

With the Lethal Weapon TV series, there are tricks to get around the restrictions on violence. Imagination works just as well as outright showing the act of violence, possibly more so because the audience is filling in the blanks with its own past viewing experience. Car chases and explosions aren’t considered as violent as a shoot-out with every bullet hit detailed in a shower of blood. Even cutting out the blood reduces the impact of the violence. The other issue, timing, works in favour of the TV series, allowing the audience to see Murtaugh’s relationship with his family more often without it being the focus every episode. Riggs, his deathwish, and his turn around can also be given more depth, spreading the issues over several episodes.

The critical issue with a Lethal Weapon TV series, though, is the chemistry between the leads. In the movies, Gibson and Glover played off each other so well, a remake would be impossible. Yet, in the TV series, the impossible happens each week. The casting of Clayne Crawford as Riggs and Damon Wayans as Murtaugh brings in the chemistry as the two work well together. They may not play off each other the same way Gibson and Glover did, but they do bring a new approach.

Another issue is the passage of time. The pilot episode of the TV series aired almost thirty years after the first movie’s release. In that time, there have been changes in how police departments operate, especially when it comes to officers like Riggs who are suffering from mental health problems. The Captain’s attitude in the first movie, that Riggs is bucking for a disability pension, would have him written up by the staff psychiatrist. Instead, Riggs has regular sessions with the psychiatrist, Dr. Maureen Cahill as played by Jordana Brewster, with her word being what allows him to work. The plots of the first two movies would need heavy rewrites to be adapted as episodes, should the series chose to use them; the end of US involvement in Viet Nam was over forty years ago and Apartheid in South Africa ended in 1991.

The series changes a few details. Murtaugh’s wife is now a defense attorney. Riggs is now from Texas. Murtaugh isn’t so much hoping for his last years on the force before retirement to be quiet; he now has a pacemaker and is under orders from his doctor and his wife to take things easy. These changes don’t affect the core of the show; Murtaugh is still a family man who loves his wife and kids while Riggs is a family man who is despondent after losing his wife in a car crash.

The opening scene of the pilot episode demonstrates this clearly. During a hostage taking after a failed bank robbery, Murtaugh is on scene working to get the situation handled quietly, with the proper people in to talk the robbers into letting everyone go with no one coming to harm. Riggs takes matters into his own hands, delivering a pizza to the robbers and exchanging himself as a hostage.and freaking out his captors by provoking them into shooting him. That wasn’t the way the two met in the movie, but it sums up both characters well. The Lethal Weapon TV series is still, at heart, a buddy cop action/comedy, with one cop wanting to keep things quiet and the other with a deathwish, fighting crime in LA while causing millions in collateral damage.

* In 1989, South Africa was still under Apartheid, a system of government suppressing the black majority by the white minority. In Lethal Weapon 2, Riggs treated the diplomat as being no better than a Nazi. The distraction Leo and Murtaugh cause at the South African embassy is well worth seeing.

Last week, Lost in Translation looked at a fan-made audio drama, including the nature of audio plays. The post goes into greater detail about the needs of an audio adaptation. This week, Lost in Translation looks at another fan audio work, Star Trek: Outpost, from Giant Gnome Productions.

Like Starship Excelsior last week, Outpost is a Star Trek fan audio series set after the end of the Dominion War. However, Outpost is set on Deep Space Three, a neglected space station near the borders of both the First Federation, first seen in “The Corbomite Maneuver”, and the Ferengi Alliance. The relative calm of the sector compared to those abutting Klingon space, Romulan space, and the ones consumed by the Dominion War meant that Starfleet did what it could to keep the station running without spending too many finite resources. Commanding the station is Captain Montaigne Buchanan, an efficiency expert who has managed to keep the station going with fewer and fewer resources. Captain Buchanan is looking forward to his efforts at the station being rewarded with a promotion to Admiral. However, the transfer of Lt. Commander Greg “Tork” Torkelson from the USS Remington to become as the station’s Executive Officer, throws a few hitches into Buchanan’s approach. Torkelson, as the Exec, also gains command of the USS Chimera, an Oberth-class starship similar to the USS Grissom from Star Trek III: The Search for Spock.

Deep Space Three has a reputation for being a place where Starfleet personnel whose careers have nosedived go to, a collection of misfits and outcasts. The Chimera‘s Chief Engineer, Chief Petty Officer Bert Knox, is one such character. His goal is to keep the Chimera functioning, going so far as to salvage other decommissioned Oberths and to install alien technologies when the proper part isn’t available. Torkelson’s arrival, though, brings in new ideas on how to make Deep Space Three relevant again. Tork’s plans include re-opening parts of the station shut down to conserve power and resources, including the station’s mall. While Torkelson’s choice to run the station – Ferengi brothers Vurk and Tirgil – may not work out as well as he hopes, Deep Space Three is beginning to turn around from its reputation. Whether it can while Orion pirates, a rogue Klingon warrior, the return of the First Federation, and the general weirdness of the Pinchot Expanse are around is another question.

As mentioned last week, audio works need to create the setting solely through sound. Redundant, but success and failure hinge on making sure the audience knows what’s around through sound cues. Outpost succeeds here; the Chimera and Deep Space Three have different sounds, and starship and station both individualize their sets even further. The bridge of the Chimera has the proper sounds as expected and is different from the engineering section and sick bay. Likewise, Deep Space Three’s command centre is different from the station’s sick bay and from the mall. And when power is lost in one episodes, the background sounds disappear.

Like Excelsior, the cast of Outpost is more than compentent, and the two productions share a couple of voice actors, Larry Phelan and Eleiece Krawiec. Of note, the father-and-son team of Ben Cromey and Doug Cromey are fun to listen to as the Vurk and Tirgil, especially their rallying cry, “We’re gonna die!” Combined with the writing, the episodes of Outpost are compelling, with characters who have depth and can be empathized with, even when they’re not immediately sympathetic.

One thing the creators of Outpost do is create “minisodes”, or mini-episodes, when at conventions. They bring in netbooks with USB microphones and get volunteers from the audience to read parts in a script to show how a show is put together. Overnight, they edit the parts together, add in the sound effects and music, then present the minisode in a panel the next day. A good example of how the creators get this done is the minisode, “Ferengi Apprentice“, recorded at the Denver Comic Con. They had some problems with the recoding due to an unshielded cable interfering with a microphone, so the episode was redone, but both versions, the original recorded at the panel and the redone one, are included to show the differences.

Star Trek: Outpost is another fan-made production that takes pains to fit in with the original work. The effects are correct for the era, and the Chimera‘s mish-mash of parts include sounds from Star Treks of old. The result is a well-done adaptation that demonstrates how to adapt well.

Last week’s Lost in Translation featured a discussion about fan adaptations, including a rationale on what works would get analyzed. This week, a look at a Star Trek fan audio productions.

Radio serials were the forerunner of today’s TV series. Families would gather around the radio and tune in favourite series. In the Thirties, ventriloquist Edgar Bergen had his own, live, show that had a large audience. Orson Welles had Mercury Theatre on the Air, the production that scared the US with War of the Worlds. The key is to engage the audience’s imagination. Unlike theatre before, movies concurrent with radio, and television afterwards, radio relies on just one sense, hearing. The cast and crew have to create an immersive setting while just using audio. Sound effects become key. The more real the situation sounds, the more the audience buys in. Creative use of sound can also create the mood desired. Welles’ War of the Worlds has a memorable scene where one plaintive voice calls out over radio, “Is there anyone out there?” over and over while the background sounds fade out one by one as the Martian advance, leaving the audience in horror of what’s happening even if they don’t realize why*.

Even with television ubiquitous these days, radio plays still abound. National Public Radio (NPR) adapted the original Star Wars trilogy into radio serials shortly after each movie was released. BBC Radio 4 still airs radio dramas on Saturdays. With the proliferation of portable devices capable of playing .mp3 files, from dedicated .mp3 players to cell phones to tablets, audio plays join music and audio books as something to listen to when the eyes are busy elsewhere.

Fan works, however, exist at the forbearance of the person or company owning the original material. Fan fiction tends to get overlooked; unless the fanfic is notorious, a blind eye is usually turned. There is also no barrier to entry when it comes to fan fiction; all that is needed is a means to write, available with all computers or even pen and paper. Some rights holders encourage fan fiction, with limitations, because of the creativity the endeavor encourages. With original visual works, like TV series and movies, the closer a fan work is to matching, the closer the work gets to being an infringement. Full video also has expenses; while the cost of professional-quality recording and editing equipment has dropped, creating sets and costumes still have material costs. If the fan production charged a fee for viewing, the work becomes a copyright and trademark infringement and corporate attack lawyers will have cease-and-desist orders issued before the first payment can be processed. There are ways around, including donation in kind, where a fan can help by providing equipment, costumes, or props that are needed.

Audio works don’t have the range of expenses a video would. Where a video would need props, sets**, and costumes, audio just needs the sound effects of those elements. The actors don’t even need to be in the same city or even continent, thanks to the Internet and cloud storage. Each actor just needs a good microphone and a way to record, which even the Windows operating system had since version 3.1. The audio production, though, needs to use sound to build the sets, so details that get taken for granted by audiences, such as subtle creaks in an old castle or the rumble of a starship’s main drive through the hull, have to be added to help the listener create the image in his or her mind. One wrong detail, even if it’s just getting a sequence of beeps on a starship’s viewscreen out of order, can break the suspension of disbelief and lose listeners.

Strength of writing is also important. Getting the audio details correct does go towards satisfying an audience, but if characters aren’t acting as expected or the plot is dull, listeners won’t tune in. Some original works, including Star Trek, Star Wars, Firefly, and Harry Potter, have settings broad enough that new stories can be created in them without ever interacting with the original characters. In the case of Star Trek, a fan work could focus on the crew of a different starship, exploring different sectors at any point in the history of the setting. The precedent already exists with Star Trek: Voyager and Star Trek: Enterprise. With Harry Potter, the novels already show a glimpse of a larger wizarding world; setting an audio series at a different wizard school isn’t farfetched. There’s room to play, and that sort of room allows for creative interpretations. Let’s take a look at a fan-made Star Trek audio series.

Starship Excelsior began its first season in 2007. Set on board the Sovereign-class starship, the USS Excelsior, hull code NCC-2000C, the series is in its fourth season. The main plot of the first three seasons picks up to dangling plot threads from Star Trek: The Next Generation and ties them together as the crew of the Excelsior investigates an anomaly that leads into dark revelations that threaten the survival of not just the Federation, but the entire galaxy. The fourth season starts a new arc as the Excelsior begins an exploration mission, with a mixture of lighter and darker episodes, though some still harken back to the earlier episodes.

The cast of characters consists of the Starfleet officers assigned to the Excelsior. The ship’s captain, Alcar Dovan, received the command after the previous commander, Rachel Cortez, died in action. Dovin joined Starfleet to explore, not to engage in military action, but he has excelled at surviving in battles, something he has grown to hate. His first officer, Alecz Lorhrok, is an unjoined Trill, chosen to be the exec by Dovan. The by-the-book operations manager, Neeva, is an Orion, dealing with the difficulties of being one of the few of her people in Starfleet. The chief of security, Asuka Yubari, was severely wounded in the special forces, moved to intelligence, then was assigned to the Excelsior. The helmsman, Bev Rol, also served in intelligence, where he lost his idealism. The ship’s surgeon, Doctor Melissa Sharp, wanted to be a researcher, away from patients, but found her career stalled as a result of her beliefs before signing up on the Excelsior. The characters all have their own motivations, from Dr. Sharp’s opposition to military engagements to Rol’s atonement for past misdeeds. They clash, they argue, they laugh, they are fully formed, brought to life by actors who could easily get into professional voice work if they so choose.

The writing of the series is tight and takes into account Trek canon. As mentioned about, the major plot of the first three seasons centred around two dangling plot threads from Star Trek: The Next Generation, one involving the Borg. The first three seasons are also one continuous story, as opposed to being episodic. Missing an episode means missing plot and character developments. The fourth season has more single-story episodes, but still has an arc to it. Listeners can easily get attached to the characters and worry about their survival and success. There are times when the writers’ fannish tendencies*** show up; Dovan’s exclamations owe a lot to Battlestar Galactica and Star Wars, with a nod to Terry Pratchett’s Discworld with a colour that Bolian vision can see that humans can’t.

The audio sets are also built well. The sounds that are expected from a Starfleet vessel are all there, from the rumbling of the engines to the beeps of consoles and PADDs to the alarm klaxons. Even if someone was just tuning into the middle of an episode, the effects would be enough to tell them where the story was set. The result is a series that is very much Star Trek, though in the darker realms of the franchise.

Of special note, Starship Excelsior ran a Kickstarter campaign to create an episode for the fiftieth anniversary of /Star Trek/’s first airing. The campaign was more than successful, letting them rent a proper recording studio and fly their audio engineer in from Toronto. More than that, the success allowed the series get Nichelle Nichols (Uhura), Walter Koenig (Chekov), Robin Curtis (Saavik, The Search for Spock), Joanne Linville (the Romulan Commander in “The Enterprise Incident”), and Jack Donner (Subcommander Tal, “The Enterprise Incident”) to reprise their original characters in a new story that still ties into the Starship Excelsior storyline. “Tomorrow’s Excelsior” is a one hour, forty minute story where Uhura and Chekov must save Starfleet, the Federation, the galaxy, and the future while avoiding war with the Romulans, with a solution that fits well with their characters. The series took care in emphasizing in the Kickstarter campaign that all money raised would be put into the production of the episode, with the main costs being getting the actors they wanted. The episode is available for free from Starship Excelsior‘s website.

* Creative use of sound continues even today. Alien, a science fiction horror movie, removed background music, leaving the audience no cues on what was about to happen.

** Even with green screening and CGI available, some physical elements are still needed, if only to give the actors something to play off.

*** To be fair, even professional works will have this sort of thing. The Serenity from Firefly had a cameo in the Battlestar Galactica reboot, appearing overhead on Caprica.

With two exceptions, Lost in Translation has looked at professionally done work. The first exception, The Four Players, was to show just how far off Super Mario Bros. was from the mark. The second, Star Wreck: In the Pirkinning, demonstrated an eye to detail needed to maintain a parody of not one but two science fiction series, Star Trek: The Next Generation and Babylon 5. The reason for analysing the professional work is two-fold. The main reason is that hte professional work is more available to a general audience. Movies get released to the silver screen, then is made available on DVD/Blu-Ray, digital streaming, video on demand, and other methods. TV series get rerun via syndication and released much like movies.

The other reason is that fan work is variable. Quality runs the gamut from rookies learning how to write and use the equipment to professional-level capabilities that may make the professional work look inadequate. Sometimes, the fan work can lead to getting a paid position; a number of fan droid designers, inspired by R2-D2 in Star Wars were hired to develop build robots for The Force Awakens. At the other end, fanfiction has a reputation for being barely comprehensible, whatever the truth of the matter is.

For the most part, the fans are creating because of a love of the original work. Each fan brings in a different interpretation of the original, seeing different elements despite the shared experiences. Sometimes the interpretation is brilliant, a new look at the original. Other times, the interpretation comes out of left field and has almost no connection to the original at all. it is easy to spot when something is mean-spirited; there’s almost no eye to detail, just characters wearing the names and acting so far out of character, it’s easier to find points that are related to the original work because they just stand out.

As mentioned, Lost in Translation has reviewed two fan adaptations. However, the goal with fan production is to show either how well the adaptation works or to show how far a professional adaptation missed the mark. There is little to gain by picking apart a lacking fan adaptation; there are too many issues and it’s just not fair to a potential budding fan to rip apart a work. Few fans are deliberately trying to make a bad interpretation; lack of experience is a leading cause. Thus, Lost in Translation will point out and analyze the fan adaptations that are a good reflection of original works. It is a bias, but good adaptations do not necessarily mean for pay. Professional quality can come from all quarters.