- (This column is posted at www.StevenSavage.com, www.SeventhSanctum.com, and Steve’s Tumblr)

It’s here! The second book in the Way With Worlds series – in both Print and Kindle! Go get it now!

To celebrate, here’s what I’m doing this weekend!

- The first Way With Worlds Book will be on sale from April first for a week on Kindle. It’s your chance to catch up!

- The Power Of Creative Paths, my guide to creative methods, will be free this weekend and Monday!

So now you’ve got two books on worldbuilding to help you out. Spread the word!

But there’s more coming! I’m working on a series of smaller, more focused, more personal worldbuilding books – small, 99-cent ebooks to help you focus on specific subjects in more of a coaching manner. Those will start coming out this summer, so stay tuned!

Meanwhile, keep writing, keep gaming, and keep creating new worlds!

– Steve

Spunky girl detectives can be traced back to one source – Nancy Drew. The character first appeared in 1930 with the publication of The Secret of the Old Clock, sending the titian-haired sleuth into fame. The original Nancy Drew Mystery Stories series ran for 175 books from 1930 until 2003, with more books under new series since then, along with a series of video games from Her Interactive.

Nancy plies her trade as an amateur sleuth in the fictional town of River Heights, where she lives with her lawyer father, Carson Drew, and their housekeeper, Hannah Gruen. Nancy’s mother died long before her adventures started, leaving Hannah in the role of a surrogate mother. Carson’s work leaves him away from home for extended periods, giving Nancy a sense of independence that allows her to investigate. However, Nancy isn’t alone. She has her cousins, the feminine Bess Marvin and the tomboy George Fayne, and her beau, Ned Nickerson, along to help her. Nancy is self-sufficient, capable of not only getting into trouble but getting herself out on her own.

Behind the scenes, the Nancy Drew Mystery Stories was created as the distaff side for the Hardy Boys for the Stratemeyer Syndicate. Ghostwriters using the pen name Carolyn Keene wrote the stories based on plot outlines created by Edward Stratemeyer and his daughters. The early years saw new books published four times a year; these releases were always anticipated and sold well.

With a long history, Nancy inevitably would wind up on the silver screen. Warner Bros. released a series of four movies in 1938 and 1939. Nancy has also appeared on television, with a series in 1977 starring Pamela Sue Martin. Hollywood is attracted to popular characters, and Nancy Drew has maintained her popularity over the years since her first appearance.

With such a long history, adapting the character poses some problems. The biggest is the changes in culture since 1930. The racism of the Thirties just does not fly today. The expectations of young women have changed. No longer are teenaged girls expected to go to college to get degrees in Home Economics; instead, women are breaking through barriers in all walks of life. An adaptation would have to work out how to balance what is acceptable in entertainment today while still keeping the core of the character.

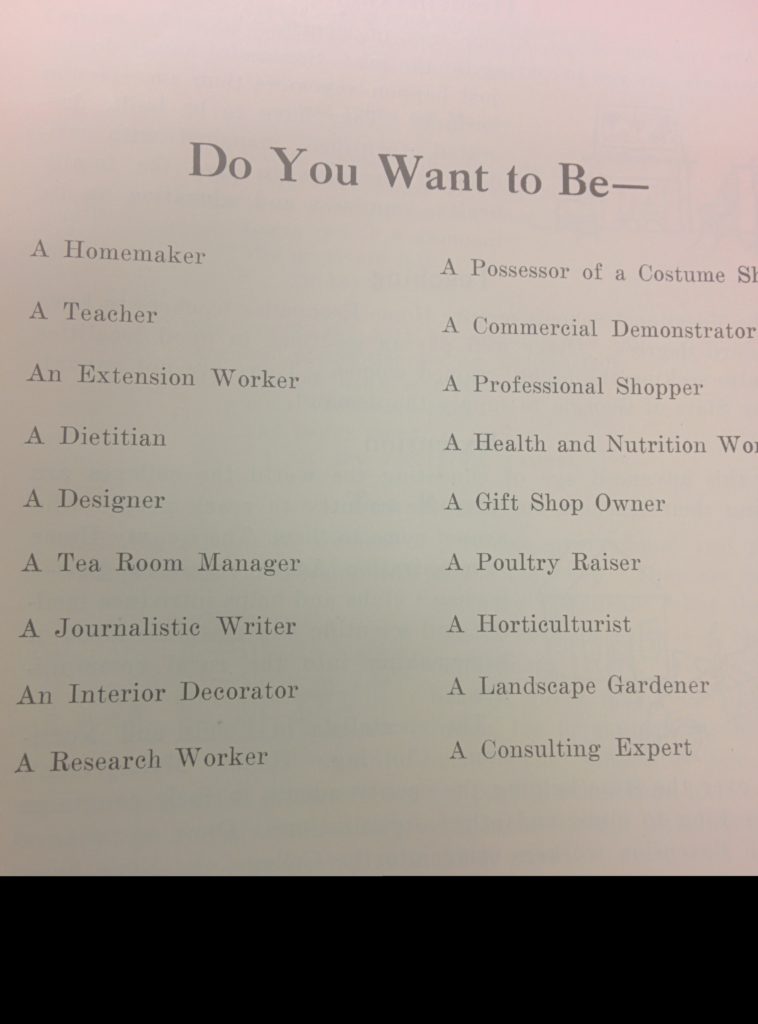

Welcome to a woman’s destiny in 1924, via the Georgia State College of Agriculture bulletin, “What Women Can Do”.

With this in mind, it’s time to look at the 2007 adaptation by Warner Bros, simply titled Nancy Drew. The movie starred Emma Roberts as the titian haired sleuth, with Tate Donovan as Carson Drew and Max Theriot as Ned Nickerson. The story starts in River Heights at the tail end of one of Nancy’s cases, inside a church as she talks a pair of crooks into surrendering to the police after they caught her. The commotion, though not only draws out the town to root for Nancy but also brings Carson out from work, which happened to be in court at the time. As a result, Carson gets Nancy to promise to no sleuthing while they are in Los Angeles.

However, Carson forgot that Nancy arranged for the housing arrangements in LA. She found a haunted mansion once owned by the famed actress Delilah Dreycott, who disappeared in mysterious circumstances twenty-five years prior. The mystery draws Nancy in, despite her promise to her father to not sleuth. What should be a simple investigation, though, leads to threatening phone calls and the discovery of Delilah’s illegitimate daughter, Jane Brighton, played by Rachel Leigh Cook. After meeting Jane, Nancy changes the direction of her investigation into finding the late actress’s will to help Jane and her daughter. As expected, Nancy does get kidnapped after finding the will, but she escapes on her own, and is able to reveal the mastermind behind the plot.

Emma Roberts as Nancy was able to carry the movie on her own, portraying the girl detective as competent and capable. While her classmates in LA made fun of Nancy’s fashion choices, the look was based on illustrations in the books, updated for today. Outside Los Angeles, Nancy wouldn’t look too out of place, eccentric but not decades out of date. The movie’s story was original but used elements from the books, including Nancy’s penchant for getting captured by the villain’s henchmen and for escaping. The movie also showed Nancy as a capable young woman, independent but still her father’s daughter. Just as important, Nancy’s hair was titian, not blonde nor brunette.

The movie also tossed in a few Easter eggs for fans. Several of Delilah’s old films took their names from the Nancy Drew Mystery Stories, including Mystery of the Lilac Inn. Nancy had a blue ragtop roadster, a Nash Metropolitan, the same colour as it had in the books. Bess and George made quick appearances at the beginning of the movie while it was still in River Heights, and it was possible to tell the cousins apart just by their clothes. Ned appears both at the beginning and comes back in the middle of the movie with the roadster.

While the movie wasn’t based on any one book in any of the various Nancy Drew series, it was based on an amalgamation of Nancys through the years, updating her while still keeping her true to her nature. Nancy Drew was aimed at the same audience that the books are, but made sure that the clues were there to be seen by viewers as well as Nancy herself. The result is a work that takes pains to bring a character up to date without losing what made her so popular in the first place.

The Color Generator is in Beta and Seventh Sanctum!

This generator makes colors that aren’t or should be, are mysterious or otherworldly. Inspired by the Neathbow of Fallen London as well as things like Octarine in Discworld, it’s a way to make colors that aren’t your standard spectrum – or lurk in between the colors we know.

A few examples:

- Anihe – A deep blueish-green. Under light of this color mirrors show falsehoods.

- Celvoweur – The penultimate orange. Under light of this color people have religious visions.

- Cong – The purple of the early morning sky.

- Brot – The green of half-forgotten grasslands.

- Ilva – The iridescent red of curiosity.

- Serneo – The green of leaves in legends.

- Cheppan – The purple of bravery and of the early morning sky that you fear seeing.

- Thue – A flamboyant orange. Under light of this color wounds heal.

- Cephutem – The yellow of loyalty and of half-forgotten sunlight.

- Auguahe – The muted yellow of loyalty.

The generator needs to be expanded – the names and basic shades are mostly done, but the descriptions and symbolism and effects need a lot more work. So go on, take a look, leave feedback!

- Steve

After a few weeks of heavy works, it’s time to take a small breather. To celebrate the recently passed Ides of March, it’s a good time to look at the classic Wayne & Shuster sketch, “Rinse the Blood Off My Toga“.

The death of Julius Caesar at the hands of Roman senators led by Brutus became fodder for William Shakespeare, who turned the assassination into a tragedy. The play, Julius Caesar, was first performed in 1599 and has been a regular in the repertoire of many a Shakespearean company. Julius Caesar is also a common play taught in high school English classes, thus continuing the legacy of those fateful Ides of March.

Meanwhile, Johnny Wayne and Frank Shuster* created their duo, Wayne & Shuster, after working together since high school. They went professional in 1941 on radio with CFRB in Toronto. “Rinse the Blood Off My Toga” was released on LP in 1954, and was then used for their big break with American audiences on The Ed Sullivan Show. After the show, New York City bars were offering “martinus specials” after a line from the act**. Sullivan had the duo back a record sixty-six more times over eleven years.

“Rinse the Blood Off My Toga” is a hard-boiled detective story using Julius Caesar as the starting point. The obvious place to start is after the big murder, the assassination of Caesar. Wayne’s character, Flavius Maximus, is a private Roman eye, hired by Shuster’s Brutus to find who killed Caesar. As Brutus, Shuster is giving a wink and a nod to the role the character had in the play. The sketch plays out as advertised, a hard-boiled detective story, with the various suspects coming up and being interrogated, including Calpurnia, Julius’ wife. The play’s characters are treated as if they had Mob connections as Flavius looks for Mr. Big.

As a comedy sketch, “Rinse the Blood Off My Toga” toys with the source material, going for laughs instead of accuracy. Yet, the sketch does show another way to adapt a work, by taking a different angle, either through the eyes of a minor character on the edge of the events or by bringing in a new character as an observer. Flavius Maximus wasn’t in the original Julius Caesar, but the mixing of genres allows him to insert himself into the aftermath of the assassination and bring Brutus to justice.

* Frank Shuster’s cousin Joe also became famous, through Superman. His son-in-law, Lorne Michaels, also is famous, having created Saturday Night Live.

** Flavius: “I’d like a martinus.”

Cicero: “Don’t you mean a martini?”

Flavius: “If I want two, I’ll ask for them.”

Last week’s look at Mercury Theater’s War of the Worlds saw HG Wells’ science fiction story about the invasion of Britain by Martian war tripods moved wholesale to New Jersey. The radio drama is a classic presentation; yet, localization is becoming problematic today, with concerns about live action version of both Ghost in the Shell and Akira around. Today’s post will look at the issues around localizations.

A localization is an adaptation remade for a new audience, taking into account what the culture that the audience lives in. An localization made for an American audience is better known as an Americanization. Several popular television series came about because of Americanization, including All in the Family, after the UK series Till Death Do Us Part; Three’s Company, after the UK series Man About the House, and The Office, after the UK series of the same name. Not every attempt to Americanize a foreign work succeeds, though. The nigh-infamous clip of Saban’s Sailor Moon missed the core of what the original was about in an attempt to bring the anime across the ocean.

The difference between Mercury Theater’s adaptation of The War of the Worlds and Saban’s failed Sailor Moon adaptation lies in the intent. Mercury Theater’s goal was to scare New York City; bringing over the Martian invasion from the British countryside to New Jersey, across the river from the Big Apple. The biggest changes to the story were location and time, with a focus that changed from a first-person narrative to eyewitness news reports on the radio. To the end Mercury Theater wanted, the action had to be close to the listeners. An invasion of Britain would not have had the immediate impact that destroying Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, had.

With Saban’s Sailor Moon, the intent was to bring in a popular anime series without necessarily bringing the aninme. The new series was part live action, part animated, with a superficial resemblance to the original. However, the core of the original Sailor Moon was, ultimately, the concept of a shoujo heroine in Japanese fiction. Usagi is the least likely person to ever save the world multiple times. She’s not the smartest, not the strongest, and not the bravest, but she has heart. Her heart is how she defeats villain after villain. Sailor Moon wins not because she’s the most powerful, but because she believes in her friends and is willing to extend a hand in friendship. Usagi is the hero, not Sailor Moon, and that’s a concept that can get easily lost in translation.

Note that both adaptations have a target audience. Even Saban’s attempt at localizing /Sailor Moon/ was based on the company’s knowledge of American children’s television. Likewise, the three TV series mentioned at the beginning were well aware of the audience that would be watching. Norman Lear, creator of All in the Family, had seen episodes of Till Death Do Us Part and was struck by how much the relationship portrayed there resembled the one he had with his father. All in the Family was built upon that resemblance, allowing a near-universal experience be the core. The American version of The Office reflected the American work experience, which, because of differences in labour laws between the US and the UK, results in a different dynamic.

Television has the luxury of being able to target a specific audience. The bulk of the television work out of Hollywood is meant for American consumption, with foreign markets a bonus. Movies, though, don’t have that option. With budgets rising and frequently break the $200 million mark, studios can’t rely on the domestic take to break even. Films on the big screen need to have a broader appeal today. A work that is known internationally is a draw studios want, but too many try to Americanize to appease the domestic market. Some of these works, though, don’t translate well. Ganriki.org has gone into details about the problems surrounding the live action Akira movie, from the screenplay to the purpose of the movie. Essentially, the US was never the target of the only two atomic weapons used in war, and never had to rebuild after a defeat, something that is inseparable from Akira.

Moving away from anime, Harry Potter was spared from localization thanks to JK Rowling being able to set terms, and that was from the sheer popularity of the books. Like Akira, Harry Potter is very much set in the country of its origin. Britain has a long history, with castles that are older than current North American nations. Boarding schools are common enough that the average person in the UK will have a good idea of what being at one is like. The wizarding world in the books is as old as the country. Moving Hogwarts to the US loses the sense of foreboding history that the school has in the books. The characters reflect British society throughout time, from the upper class Malfoys to the common Weasleys. Harry Potter also demonstrates the power of the draw. Audiences wanted the Harry they read about, not one that was transplanted to another country. With works that have the widespread appeal like Harry Potter, alienating the audience is not a good idea.

Similar to the problems facing Akira and a hypothetical American Harry Potter, the 1998 Godzilla lost some important elements on moving the action to New York City. While Tokyo and NYC are major cities along a coast, filled with tall buildings, a lot of people, and neon, the similarities end there. The first American Godzilla movie forgot that the eponymous monster was a result of the nuclear age, going back to the two atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, followed by the nuclear weapon tests in the Pacific. It is possible to have a story featuring giant monsters stomping through an American city, but Godzilla has cultural ties that don’t make the journey to the West easily. The 2014 Godzilla acknowledges the nature of the monster’s origin, starting him near Japan before sending him westward.

What can help with localization is changing the nature of the story. War of the Worlds updated the story; the American military, with its mechanization, its improved communications, its aerial capabilities, all not available in 1897, still lost to the Martian invaders. The Seven Samurai, a story based in Japanese samurai, was successfully translated to the American West with The Magnficent Seven and then moved into science fiction with Battle Beyond the Stars. The goal in these adaptations wasn’t so much to localize, but to retell the story within the new trappings. Ronin became guns-for-hire, who then became starfaring mercenaries; all three are similar, but are very much dependent on their culture and their settings. Similarly, Phantom of the Paradise took the core ideas from both Faust and The Phantom of the Opera and combined the stories and bringing them into the Seventies, with a villainous record producer in the role of Faust and a hapless songwriter as the Phantom.

Sometimes, though, the effort to localize doesn’t pay off. The film version of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo kept the story in Sweden. The plot could have easily been moved to an American setting, yet the makers kept the work in Sweden, with most of the cast being Swedish. Part of the decision comes from the original work; the novel is set in Sweden, using various towns in the country. Moving the work would mean finding a similar location, It was easier to keep the Swedish locations.

Localization isn’t necessarily a negative. Presenting a story that the intended audience can understand culturally can get the point of the story across. The problems begin when the original’s culture isn’t accounted for when translating the work. Care needs to be taken, and there are some works that don’t translate well, even if the two countries involved share a common language.

(This column is posted at www.StevenSavage.com, www.SeventhSanctum.com, and Steve’s Tumblr)

Here’s some samples from the latest generator. It generates colors, inspired by the Neathbow from Sunless Sea/Fallen London – http://thefifthcity.wikia.com/wiki/The_Neathbow

I loved the idea of creating new colors, so here we go! It’s probably about 25%-33% done at this time – there’s a nice amount of detail, but far more coming.

So tell me what you think!

- Moten – The mellow orange of joy.

- Lebode – The purple of the evening sky in your memories.

- Elde – The blue of shallow water that you fear seeing.

- Cesque – An iridescent green. Under light of this color plants grow.

- Khuppen – The one true green.

- Bitohoem – A deep greenish-yellow. Those that see this color have glimpses of the future.

- Cerate – The yellow of sunlight falling on the incurious. Under light of this color plants grow.

– Steve

This week’s subject, The Mercury Theater presentation of HG Wells’ War of the Worlds demonstrates two elements that have recurred here at Lost in Translation. The first is the medium of the adaptation and how time available affects how the original is adapted. The second is the passage of time and how it affects an adaptation made decades after the original.

As has been mentioned in a number of previous Lost in Translation entries, the time allotted for a work has a direct impact on how the adaptation is handled. Long form works, such as novels and television series, allow for a deeper examination of characters and events. Shorter works, including movies, need to get to the point straight away. Details get lost or bundled together, whether character or setting. Even films trying to be as faithful as possible to an original work will have to lose details just to keep to a reasonable running time.

The passage of time and the advances in technology can affect how a work is seen. Unless the adaptation is treating the original as a period piece, the changes in available technology can cause problems. This typically happens when an original work is set in “now”, whenever that “now” was. For example, “modern” works from the Eighties often show characters using car phones, large blocky handsets plugged into the vehicle’s cigarette lighter port. If the work were to be brought to the today of the 2010s, that blocky car phone would be replaced with a smartphone with far better coverage and no need to go through a mobile operator, which may reduce the tension in a scene.

Wells’ War of the Worlds was first published in 1897 as a serial, and told from a first-person perspective as a journal by the narrator. The story details the Martian invasion of Earth, starting from the first impact of a Martian cylinder in the English countryside. The locals are abuzz, wondering what the object is. After the Martian recovers from its journey and landing, it begins to use a terrible weapon, a heat ray, against the crowds. The Army is sent in, with cavalry and horse-drawn artillery, to deal with the threat; but with more cylinders falling, each one containing a Martian war tripod, the soldiers stood no chance.

The narrator tells of his journeys and the people he meets during the initial attack and the response. News travels by word of mouth, mainly from the narrator as he walks through the countryside to reuinite with his wife and escape the destruction. The Army, though, uses heliographs to maintain communications between units. London is unaware of the danger despite news reports trickling out until the tripods reach the city three days after landing. The Martians have a second weapon, a black smoke that kills anything that breathes it. British civilization begins to break down as the Martians march unimpeded. The mighty British Empire is brought to its knees. The only thing that saved the Empire and the world was microbes, bacteria that humanity had a resistance to that the Martians did not.

The 1890s saw the British Empire at its height, with the sun never setting on it. The Industrial Revolution fifty years prior brought along mechanization, allowing for steam engines, railways, and ironclad ships. Tensions between empires existed, with the expectation that one or another would try to invade Britain. With War of the Worlds, Wells introduced an invader that was more than a match for the British military forces.

In 1938, much had changed. The horse-and-carriage gave way to the automobile and radio allowed for faster transmission of news to listeners. The Great War brought down several empires and introduced new forms of warfare. The threat of war with Nazi German loomed. Orson Welles and his Mercury Theater brought the 1897 story up to date in a sixty minute radio drama on October 30, 1938, the day before Hallowe’en.

The radio version of War of the Worlds made several changes. The setting was localized to the area near New York City. Scaring a large radio market is easier when using areas local to it than using English towns like Woking, home to HG Wells. The second was to accelerate the first book of the novel. Welles used the immediacy of radio to drive the first two-thirds of the drama, having events happen in almost real time. The show is interrupted by breaking news from Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, an alien cylinder crashing into a farmer’s field. The cylinder reveals itself as a hostile machine, firing a heat ray. The station then turned over its facilities to state militia to allow for better communications, allowing the audience to follow the action. The black smoke has a more immediate impact listening to an artillery battery succumbing to it. Another scene has an Air Force squadron trying an aerial attack against the tripods and being shot down by heat rays, something that Wells couldn’t have added as the Wright Brothers hadn’t yet made their first powered flight. And like London in the novel, New York City tries to evacuate.

The last third has Welles’ character, Professor Richard Pearson, formerly of the Princeton Observatory, wandering through the New Jersey countryside, meeting a number of people the same way Wells’ unnamed narrator had in the novel. Pearson is trapped at Grover’s Mill, the initial landing site of the invasion. His life has changed; time passes without being marked, and his primary goal has become survival. The survivalist Pearson meets is taken directly from the novel, with almost no changes except for time constraints.

HG Wells’ lone first-person narrator may work in a novel, allowing the reader to experience events through the character. Radio, though, loses that connection if someone narrates from that perspective. Instead, breaking news with no apparent filtering allows the listeners to bring their own emotions in. The invasion happens faster on radio than in the novel, but response times have also increased. Cavalry in 1938 means tanks and aircraft, not horses. Radio is far more immediate than even telegram. The listener’s response is more raw; the separation that exists between book and reader is reduced or even removed on radio, especially when the format used is a news broadcast. The most heartbreaking moment is a radio operator, call sign 2XQL, calling out, “Is there anyone on the air? Is there anyone on the air? Is there anyone?”

Mercury Theater’s adaptation demonstrates the elements that can be in the way when translating a work into a new medium. What works in one medium may not work in another. Wells’ lush paragraphs of description don’t translate into radio. Instead, the radio work has to build the setting through words and sounds. The heat ray’s effects, from the sound of it firing to the screams of its victims, were demonstrated. The discovery of the cylinder is treated as breaking news, broadcast, instead of being a curiosity for the townsfolk of Woking. However, despite the restrictions and the localization, the radio drama is a good adaptation, getting to the heart of the novel.

(This column is posted at www.StevenSavage.com, www.SeventhSanctum.com, and Steve’s Tumblr)

OK everyone, Way With Worlds Book 2 review copies are ready! So if you want to review contact me and let me know about your interest, if you have a blog, where you can review (amazon is appreciated), etc.!

Right now it’s looking like it’ll be out the very end of March or early April.

– Steve