Mighty Morphin Power Rangers‘s history starts in Japan. Toei, developed Sentai, a series about masked heroes fighting monsters, in the Sixties. After a deal with Marvel to bring over some of the comic company’s heroes resulted in mecha getting added to sentai series, Toei continued to add giant robots, creating Super Sentai. The sixteenth series, Kyōryū Sentai Zyuranger, caught the attention of Haim Saban, owner of Saban Entertainment. Saban worked out a deal to get the footage from Zyuranger to which he’d use the action scene and create new stories to go with them. Mighty Morphin Power Rangers debuted in 1993.

The original Power Rangers, Jason Lee Scott, Kimberly Hart, Zack Taylor, Trini Kwan and Billy Cranston, were recruited after the sage Zordon ordered his robot aide, Alpha 5, to find “five teenagers with attitude.” Zordon needed a team to stop Rita Repulsa, an alien sorceress who escaped imprisonment after 10 000 years. To help fight Rita and her monsters, the Rangers received Zords, mecha that can combine into the MegaZord. The Rangers defeat Rita’s monsters regularly, but the sorceress has a new plan – defeat the Rangers with one of their own. She kidnaps the Green Ranger, Tommy Oliver, and turns him against the others. Tommy does break free of the brainwashing and aids the others against her. The series sold a number of toys, from action figures to Zords. The effects at times were weak, the result of being a weekly series in Japan. However, the series had a following. The franchise is now in its twenty-fourth season with Power Rangers Ninja Steel.

As is the way of Hollywood, a popular TV series will be adapted. Despite being in its twenty-fourth season, the studio went back to the beginning, Mighty Morphin Power Rangers. There is a tendency for film makers to turn a children’s series darker and grittier to the point where the feel is off. With a series featuring martial arts, the potential for a grimdark remake existed. Instead, the movie took a different approach, acting as an origin for the Rangers.

The movie starts at the beginning of the Cenozoic Era with a battle going badly for the Power Rangers. Red Ranger Zordon, played by Bryan Cranston, orders Alpha 5, voiced by Bill Hadar, to send a meteor on his position. This desperate act of self-sacrifice is to protect the Earth’s Zeo Crystal and the Rangers’ Power Coins from Rita Repulsa, played by Elizabeth Banks. The meteor wipes out the dinosaurs, and buries not only the Zeo Crystal and the Power Coins, but sends Rita deep into the ocean.

Millions of years later, Jason Scott, played by Dacre Montgomery, makes a bad decision in trying to steal a mascot and winds up injuring his leg, destroying a potential career in football, placed under house arrest, and sent to detention. While serving detention, he meets Billy Cranston, played by RJ Cyler, and Kimberly Hart, played by Naomi Scott. Billy is in detention for blowing up his lunch box. Kimberly is there because she forwarded an image of her cheerleader friend throughout school. Jason becomes Billy’s friend after stopping a bully from tormenting him, though the feeling isn’t immediately reciprocated. Billy is a genius with electronics and is able to fool the tracker Jason wears as part of his house arrest.

In return for the help, Jason drives Billy up to a gold mine. Billy’s father had been trying to locate something hidden at the mine, and Billy continued the search after his death. He sets up the explosives and detonates them, getting the attention of Kimberly and two other classmates, Trini Kwan, played by Becky G, and Zach Taylor, played by Ludi Lin, are also at the mine and are drawn to the explosion. While Jason, Kimberly, Trini, and Zach argue about why they are all at the mine, Billy realizes that the rock wall is collapsing. The collapse reveals five unusual rocks, red, blue, pink, yellow, and black. Each of the teens grabs one and, with sirens approaching, runs away. Eventually, they all make it into Billy’s van. Jason tries to out run a train to escape both mine security and the police.

Out on the ocean, a fishing boat drags in its last haul of the day. Within the net of fish is the body of a woman. The boat’s skipper calls in for the police to meet the boat at the docks. The body isn’t quite so dead, though. Rita survived, frozen in the ocean until pulled on board. When one of Angel Grove’s finest arrives to investigate, he is surprised that the body not only isn’t dead but is trying to kill him.

Jason wakes up the next morning surprised to be alive and unsure of just how he got home. He gets out of bed, then notices that he isn’t wearing his knee brace. The red stone he discovered at the mine is still with him, even if he leaves it in another room. Jason also discovers that he has superhuman strength. He returns to the mine, where he sees the wreckage of Billy’s van. The other teenagers have also returned. More or less as a group, they explore the mine and discover a long buried spaceship deep under the rock. The ship’s caretaker, Alpha 5, rounds up the group and brings them to the central chamber to meet Zordon, who is now part of the ship’s computer matrix. Zordon welcomes the new Power Rangers and warns them that Rita will be at full strength again in eleven days. The new Rangers need to train and to learn to morph.

While their training, while painful, is difficult, the new Rangers do learn. Alpha 5 presents holographic versions of Rita’s Putties, the minions she uses as the first wave. Morphing, though, is another matter. None of the Rangers are able to morph at first. Even after Alpha 5 shows the Rangers their Zords, mecha that took the shape of the dominant life form of the Cenozoic Era, the teens aren’t able to morph. The closest any of them get is Billy, who morphs into his blue armour while breaking up a fight between Jason and Zack.

Rita keeps busy while the Rangers train. She collects gold to recreate her monster Goldar, who will be able to dig to retrieve Earth’s Zeo Crystal, dooming the world and giving her the ability to destroy other planets. Rita isn’t picky about where she gets her gold, either. Some of her victims have their gold fillings removed. She senses the other Power Coins and realizes that new Rangers have been discovered, in part because she had been the Green Ranger under Zordon’s leadership until she turned her back on her oath. Rita breaks into Trini’s home to have her send a message to the others to be at the docks.

Trini tells her fellow Rangers about Rita. Despite not being able to morph yet, Jason decides that this is the best time for them to take down Rita. Rita, though, is more than ready for them and easily defeats the group. She knows one of them has the location of the Zeo Crystal and threatens to kill the Rangers one by one until she gets it. Billy, who managed to work out where the Crystal is, doesn’t want to lose any of his new friends and gives her the key words without completely giving away the location.

It takes a tragedy to turn the Rangers from a group of teenagers into a proper team. The death of a teammate makes them realize that each of them would gladly sacrifice their life for the others. The Morphing Grid unlocks and instead of Zordon returning, the dead teammate does. The team morphs for the first time and heads out to fight Rita once again. Rita, though, sends her Putties against them at the ship. The fight is difficult, but when Zach brings out his Zord to even the odds, the others follow suit. The Putties defeated, the Rangers ride out to save Angel Grove from Rita and her monster.

Unlike the TV series, the movie has the advantage of being written as one whole instead of having to incorporate existing footage from Zyuranger with a new script. The formular of the series – Rita hatches a scheme, sends out her Putties and her monster of the week, Putties get defeated, monster forces the Rangers to call their Zords, Rita makes her monster grow, and the Rangers summon the MegaZord – is in the movie, but the movie isn’t just the formula. Instead, the formula provides a scaffold to build on, and gets reshaped in the process. The heart of the movie is the team and how the Rangers come together.

Each Ranger has a problem to overcome. Jason’s is that he is impulsive and prone to self-sabotage. Kimberly was a mean girl who had to face up to what she did. Zach is worried about his mother and being alone if anything happens to her. Trini is discovering that she is a lesbian and feels that she’s an outsider even in her own family. Billy is on the autistic spectrum and is well aware of the problems he faces as a result. By being able to move past their problems and open up to each other, they turn from a group of teenagers to a team of Power Rangers. Each of the Rangers’ problems comes from a real place. None of them are sensationalized. Billy’s autism is one of the more realistic portrayals around, as is Trini’s feeling of being an outsider because of her sexuality and Kimberly’s reaction to what she had done to her friend.

The casting worked. As mentioned above, RJ Cyler’s portrayal of Billy was believable. Elizabeth Banks as Rita channelled J-horror movies, with her early movement similar Ringu`s Sadako. Rita went from evil sorceress to frightening villain. Bryan Cranston’s Zordon had wisdom fighting against desire, a mentor who demanded much but knew exactly what the stakes were. The movie also used colour as a symbol. When the Rangers first meet and while they`re still trying to morph, the colours are muted, dark, and murky. When they become a team, the colour turns bright and full. In part, this helps show off the Zords and the Rangers colour-coded armour, but it also works to show the transition from teenager to hero.

Power Rangers takes Mighty Morphin Power Rangers and expands on it, giving the Rangers depth of character and showing them becoming heroes. Rita’s villainy also expands, showing just how evil the sorceress is. Yet, the movie never forgets its heritage and embraces it. Power Rangers is a well-done adaptation of a beloved franchise’s beginnings.

Spunky girl detectives can be traced back to one source – Nancy Drew. The character first appeared in 1930 with the publication of The Secret of the Old Clock, sending the titian-haired sleuth into fame. The original Nancy Drew Mystery Stories series ran for 175 books from 1930 until 2003, with more books under new series since then, along with a series of video games from Her Interactive.

Nancy plies her trade as an amateur sleuth in the fictional town of River Heights, where she lives with her lawyer father, Carson Drew, and their housekeeper, Hannah Gruen. Nancy’s mother died long before her adventures started, leaving Hannah in the role of a surrogate mother. Carson’s work leaves him away from home for extended periods, giving Nancy a sense of independence that allows her to investigate. However, Nancy isn’t alone. She has her cousins, the feminine Bess Marvin and the tomboy George Fayne, and her beau, Ned Nickerson, along to help her. Nancy is self-sufficient, capable of not only getting into trouble but getting herself out on her own.

Behind the scenes, the Nancy Drew Mystery Stories was created as the distaff side for the Hardy Boys for the Stratemeyer Syndicate. Ghostwriters using the pen name Carolyn Keene wrote the stories based on plot outlines created by Edward Stratemeyer and his daughters. The early years saw new books published four times a year; these releases were always anticipated and sold well.

With a long history, Nancy inevitably would wind up on the silver screen. Warner Bros. released a series of four movies in 1938 and 1939. Nancy has also appeared on television, with a series in 1977 starring Pamela Sue Martin. Hollywood is attracted to popular characters, and Nancy Drew has maintained her popularity over the years since her first appearance.

With such a long history, adapting the character poses some problems. The biggest is the changes in culture since 1930. The racism of the Thirties just does not fly today. The expectations of young women have changed. No longer are teenaged girls expected to go to college to get degrees in Home Economics; instead, women are breaking through barriers in all walks of life. An adaptation would have to work out how to balance what is acceptable in entertainment today while still keeping the core of the character.

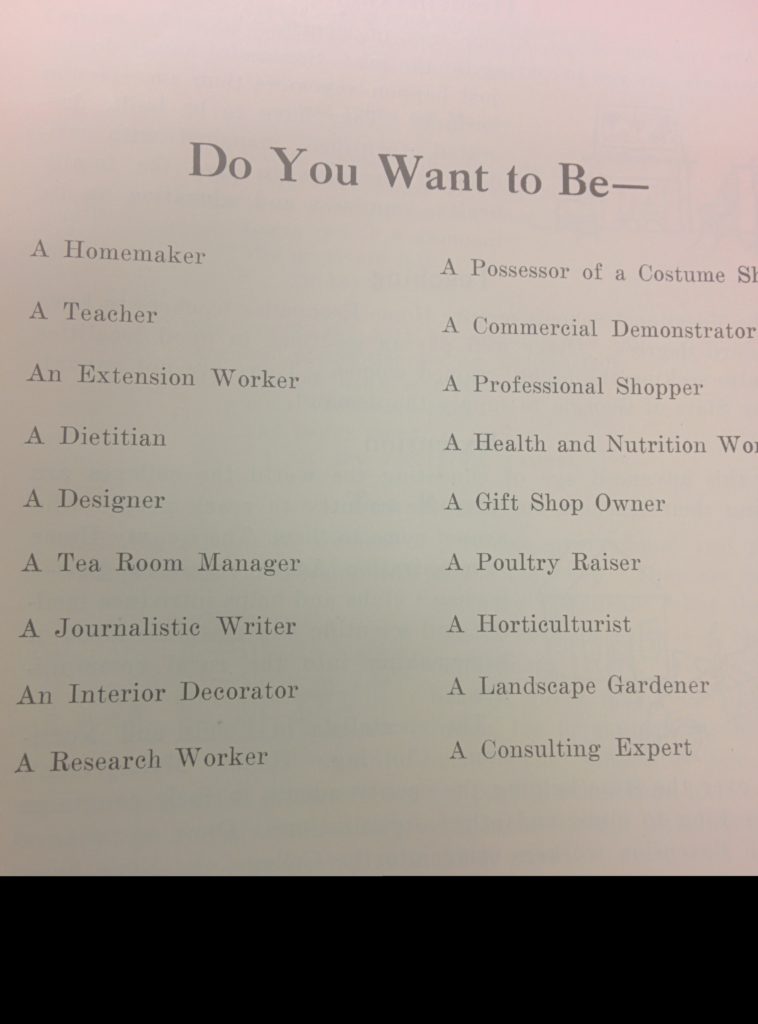

Welcome to a woman’s destiny in 1924, via the Georgia State College of Agriculture bulletin, “What Women Can Do”.

With this in mind, it’s time to look at the 2007 adaptation by Warner Bros, simply titled Nancy Drew. The movie starred Emma Roberts as the titian haired sleuth, with Tate Donovan as Carson Drew and Max Theriot as Ned Nickerson. The story starts in River Heights at the tail end of one of Nancy’s cases, inside a church as she talks a pair of crooks into surrendering to the police after they caught her. The commotion, though not only draws out the town to root for Nancy but also brings Carson out from work, which happened to be in court at the time. As a result, Carson gets Nancy to promise to no sleuthing while they are in Los Angeles.

However, Carson forgot that Nancy arranged for the housing arrangements in LA. She found a haunted mansion once owned by the famed actress Delilah Dreycott, who disappeared in mysterious circumstances twenty-five years prior. The mystery draws Nancy in, despite her promise to her father to not sleuth. What should be a simple investigation, though, leads to threatening phone calls and the discovery of Delilah’s illegitimate daughter, Jane Brighton, played by Rachel Leigh Cook. After meeting Jane, Nancy changes the direction of her investigation into finding the late actress’s will to help Jane and her daughter. As expected, Nancy does get kidnapped after finding the will, but she escapes on her own, and is able to reveal the mastermind behind the plot.

Emma Roberts as Nancy was able to carry the movie on her own, portraying the girl detective as competent and capable. While her classmates in LA made fun of Nancy’s fashion choices, the look was based on illustrations in the books, updated for today. Outside Los Angeles, Nancy wouldn’t look too out of place, eccentric but not decades out of date. The movie’s story was original but used elements from the books, including Nancy’s penchant for getting captured by the villain’s henchmen and for escaping. The movie also showed Nancy as a capable young woman, independent but still her father’s daughter. Just as important, Nancy’s hair was titian, not blonde nor brunette.

The movie also tossed in a few Easter eggs for fans. Several of Delilah’s old films took their names from the Nancy Drew Mystery Stories, including Mystery of the Lilac Inn. Nancy had a blue ragtop roadster, a Nash Metropolitan, the same colour as it had in the books. Bess and George made quick appearances at the beginning of the movie while it was still in River Heights, and it was possible to tell the cousins apart just by their clothes. Ned appears both at the beginning and comes back in the middle of the movie with the roadster.

While the movie wasn’t based on any one book in any of the various Nancy Drew series, it was based on an amalgamation of Nancys through the years, updating her while still keeping her true to her nature. Nancy Drew was aimed at the same audience that the books are, but made sure that the clues were there to be seen by viewers as well as Nancy herself. The result is a work that takes pains to bring a character up to date without losing what made her so popular in the first place.

After a few weeks of heavy works, it’s time to take a small breather. To celebrate the recently passed Ides of March, it’s a good time to look at the classic Wayne & Shuster sketch, “Rinse the Blood Off My Toga“.

The death of Julius Caesar at the hands of Roman senators led by Brutus became fodder for William Shakespeare, who turned the assassination into a tragedy. The play, Julius Caesar, was first performed in 1599 and has been a regular in the repertoire of many a Shakespearean company. Julius Caesar is also a common play taught in high school English classes, thus continuing the legacy of those fateful Ides of March.

Meanwhile, Johnny Wayne and Frank Shuster* created their duo, Wayne & Shuster, after working together since high school. They went professional in 1941 on radio with CFRB in Toronto. “Rinse the Blood Off My Toga” was released on LP in 1954, and was then used for their big break with American audiences on The Ed Sullivan Show. After the show, New York City bars were offering “martinus specials” after a line from the act**. Sullivan had the duo back a record sixty-six more times over eleven years.

“Rinse the Blood Off My Toga” is a hard-boiled detective story using Julius Caesar as the starting point. The obvious place to start is after the big murder, the assassination of Caesar. Wayne’s character, Flavius Maximus, is a private Roman eye, hired by Shuster’s Brutus to find who killed Caesar. As Brutus, Shuster is giving a wink and a nod to the role the character had in the play. The sketch plays out as advertised, a hard-boiled detective story, with the various suspects coming up and being interrogated, including Calpurnia, Julius’ wife. The play’s characters are treated as if they had Mob connections as Flavius looks for Mr. Big.

As a comedy sketch, “Rinse the Blood Off My Toga” toys with the source material, going for laughs instead of accuracy. Yet, the sketch does show another way to adapt a work, by taking a different angle, either through the eyes of a minor character on the edge of the events or by bringing in a new character as an observer. Flavius Maximus wasn’t in the original Julius Caesar, but the mixing of genres allows him to insert himself into the aftermath of the assassination and bring Brutus to justice.

* Frank Shuster’s cousin Joe also became famous, through Superman. His son-in-law, Lorne Michaels, also is famous, having created Saturday Night Live.

** Flavius: “I’d like a martinus.”

Cicero: “Don’t you mean a martini?”

Flavius: “If I want two, I’ll ask for them.”

This week’s subject, The Mercury Theater presentation of HG Wells’ War of the Worlds demonstrates two elements that have recurred here at Lost in Translation. The first is the medium of the adaptation and how time available affects how the original is adapted. The second is the passage of time and how it affects an adaptation made decades after the original.

As has been mentioned in a number of previous Lost in Translation entries, the time allotted for a work has a direct impact on how the adaptation is handled. Long form works, such as novels and television series, allow for a deeper examination of characters and events. Shorter works, including movies, need to get to the point straight away. Details get lost or bundled together, whether character or setting. Even films trying to be as faithful as possible to an original work will have to lose details just to keep to a reasonable running time.

The passage of time and the advances in technology can affect how a work is seen. Unless the adaptation is treating the original as a period piece, the changes in available technology can cause problems. This typically happens when an original work is set in “now”, whenever that “now” was. For example, “modern” works from the Eighties often show characters using car phones, large blocky handsets plugged into the vehicle’s cigarette lighter port. If the work were to be brought to the today of the 2010s, that blocky car phone would be replaced with a smartphone with far better coverage and no need to go through a mobile operator, which may reduce the tension in a scene.

Wells’ War of the Worlds was first published in 1897 as a serial, and told from a first-person perspective as a journal by the narrator. The story details the Martian invasion of Earth, starting from the first impact of a Martian cylinder in the English countryside. The locals are abuzz, wondering what the object is. After the Martian recovers from its journey and landing, it begins to use a terrible weapon, a heat ray, against the crowds. The Army is sent in, with cavalry and horse-drawn artillery, to deal with the threat; but with more cylinders falling, each one containing a Martian war tripod, the soldiers stood no chance.

The narrator tells of his journeys and the people he meets during the initial attack and the response. News travels by word of mouth, mainly from the narrator as he walks through the countryside to reuinite with his wife and escape the destruction. The Army, though, uses heliographs to maintain communications between units. London is unaware of the danger despite news reports trickling out until the tripods reach the city three days after landing. The Martians have a second weapon, a black smoke that kills anything that breathes it. British civilization begins to break down as the Martians march unimpeded. The mighty British Empire is brought to its knees. The only thing that saved the Empire and the world was microbes, bacteria that humanity had a resistance to that the Martians did not.

The 1890s saw the British Empire at its height, with the sun never setting on it. The Industrial Revolution fifty years prior brought along mechanization, allowing for steam engines, railways, and ironclad ships. Tensions between empires existed, with the expectation that one or another would try to invade Britain. With War of the Worlds, Wells introduced an invader that was more than a match for the British military forces.

In 1938, much had changed. The horse-and-carriage gave way to the automobile and radio allowed for faster transmission of news to listeners. The Great War brought down several empires and introduced new forms of warfare. The threat of war with Nazi German loomed. Orson Welles and his Mercury Theater brought the 1897 story up to date in a sixty minute radio drama on October 30, 1938, the day before Hallowe’en.

The radio version of War of the Worlds made several changes. The setting was localized to the area near New York City. Scaring a large radio market is easier when using areas local to it than using English towns like Woking, home to HG Wells. The second was to accelerate the first book of the novel. Welles used the immediacy of radio to drive the first two-thirds of the drama, having events happen in almost real time. The show is interrupted by breaking news from Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, an alien cylinder crashing into a farmer’s field. The cylinder reveals itself as a hostile machine, firing a heat ray. The station then turned over its facilities to state militia to allow for better communications, allowing the audience to follow the action. The black smoke has a more immediate impact listening to an artillery battery succumbing to it. Another scene has an Air Force squadron trying an aerial attack against the tripods and being shot down by heat rays, something that Wells couldn’t have added as the Wright Brothers hadn’t yet made their first powered flight. And like London in the novel, New York City tries to evacuate.

The last third has Welles’ character, Professor Richard Pearson, formerly of the Princeton Observatory, wandering through the New Jersey countryside, meeting a number of people the same way Wells’ unnamed narrator had in the novel. Pearson is trapped at Grover’s Mill, the initial landing site of the invasion. His life has changed; time passes without being marked, and his primary goal has become survival. The survivalist Pearson meets is taken directly from the novel, with almost no changes except for time constraints.

HG Wells’ lone first-person narrator may work in a novel, allowing the reader to experience events through the character. Radio, though, loses that connection if someone narrates from that perspective. Instead, breaking news with no apparent filtering allows the listeners to bring their own emotions in. The invasion happens faster on radio than in the novel, but response times have also increased. Cavalry in 1938 means tanks and aircraft, not horses. Radio is far more immediate than even telegram. The listener’s response is more raw; the separation that exists between book and reader is reduced or even removed on radio, especially when the format used is a news broadcast. The most heartbreaking moment is a radio operator, call sign 2XQL, calling out, “Is there anyone on the air? Is there anyone on the air? Is there anyone?”

Mercury Theater’s adaptation demonstrates the elements that can be in the way when translating a work into a new medium. What works in one medium may not work in another. Wells’ lush paragraphs of description don’t translate into radio. Instead, the radio work has to build the setting through words and sounds. The heat ray’s effects, from the sound of it firing to the screams of its victims, were demonstrated. The discovery of the cylinder is treated as breaking news, broadcast, instead of being a curiosity for the townsfolk of Woking. However, despite the restrictions and the localization, the radio drama is a good adaptation, getting to the heart of the novel.

Before diving into the analysis, a note about nice round number in the title. Two hundred reviews. I never expected to get this far. The number doesn’t include all the non-review essays, including the History of Adaptations. Thank you all for reading and thanks to Steven Savage, who not only encouraged me to write about adaptations but also supplied web space, and to Paul Brian McCoy, of Psycho Drive-In for picking up the series and providing the visuals you see each week.

Television the past few seasons is taking the lead from the silver screen, with more adaptations appearing. Both DC and Marvel are well represented withy multiple series based on their titles. But comic books aren’t the only source being used. MacGuyver brings back the classic Richard Dean Anderson series, updated for today. Likewise, the Lethal Weapon TV series updates the original movies from the the late 80s to now.

The original Lethal Weapon, released in 1987, starred Mel Gibson as Martin Riggs and Danny Glover as Roger Murtaugh, and was a buddy cop action/comedy/thriller. Murtaugh is a family man, just turning fifty, counting the days until retirement. Riggs is a new transfer from Dover, suicidal since the death of his wife in a car collision. Being Christmas, Riggs’ depression has become far more severe, with his only reason to live being the job. The staff psychiatrist wants Riggs off the force as a danger, but the Captain believes he’s bucking for a disability pension. Riggs and Murtaugh get paired up as partners, then get assigned to a case that started as an apparent suicide. The victim appeared to get high and fell off a building, but the autopsy shows that the drugs were laced with drain cleaner.

As the investigation continues, Murtaugh realizes the truth about Riggs; he is suicidal, taking risks that could get him killed. Murtaugh invites Riggs to meet his family, who adopt him. As much as Riggs is suicidal, he is a family man, just one who lost his family. Seeing the Murtaughs at home and having them welcome him helps him, a little, enough for him to realize that there’s something else to live for.

The victim’s killer is part of a former CIA black operation from Viet Nam. A long shot lead that figiratively and literally explodes in their faces leads Riggs and Murtaugh to the ring. With the two detectives getting closer, the ring, led by former general McAllister, played by Mitchell Ryan, sends his people, including Joshua, played by Gary Busey, out to deal with them, kidnapping Murtaugh’s daughter Rianne, played by Traci Wolfe. McAllister underestimates just how crazy Riggs is, though, leading to the ring’s downfall.

The core of the film came from the strength of Shane Black’s writing, Richard Donner’s direction, and the chemistry between Gibson and Glover as Riggs and Murtaugh. As a pair of buddy cops, it takes them time to get to be buddies, as both have issues that they need to work through. Once they get to that point, they trust each other, though Murtaugh isn’t always sure of Riggs’ plans.

The success of Lethal Weapon meant sequels were going to happen. In 1989, Lethal Weapon 2 brought back Riggs and Murtaugh, adding in Joe Pesci as Leo Getz, a creative accountant and middleman under witness protection while waiting to testify. Guarding Leo means pulling Riggs and Murtaugh off their main case, an investigation into a drug ring headed by a South African* diplomat that leads to Riggs discovering that the accident that killed his wife wasn’t an accident. Lethal Weapon 3, released in 1992, brings back the trio and adds Rene Russo as Lorna Cole, an Internal Affairs investigator working a different side of a case involving the funneling of submachine guns and machine pistols with armour piercing bullets from police storage to the streets through a dirty ex-cop. Lethal Weapon 4, released in 1998, brings back everyone, with Riggs and Murtaugh promoted to Captain, skipping Lieutenant, because the LAPD’s insurance company won’t insure the force if the pair are still working the streets while a Chinese human trafficking ring, overseen by Jet Li as Wah Sing Ku. Throughout the series, the relationship between Riggs and Murtaugh grows, going from assigned partners to true friends.

The movie series was popular, with Lethal Weapon 4 showing the only dip in performance at the box office. Naturally, something popular will get remade. In the case of Lethal Weapon, it was remade as a FOX TV series starting in the 2017-2017 season. Television brings a number of new restrictions. Unlike movies, where ratings exist to help audiences decide what level of sex and violence they are comfortable with, television can’t go to such extremes. Each of the Lethal Weapon films were R-rated, mostly due to a level of violence that prime time television isn’t allowed to air. Adding to the ratings issue, television has a different timing compared to film. While a television episode may run forty-three minutes after removing ads, a season may run up to twenty-two episodes, giving the series time to expand ideas over multiple airings that a movie has to get in during its one two-hour show.

With the Lethal Weapon TV series, there are tricks to get around the restrictions on violence. Imagination works just as well as outright showing the act of violence, possibly more so because the audience is filling in the blanks with its own past viewing experience. Car chases and explosions aren’t considered as violent as a shoot-out with every bullet hit detailed in a shower of blood. Even cutting out the blood reduces the impact of the violence. The other issue, timing, works in favour of the TV series, allowing the audience to see Murtaugh’s relationship with his family more often without it being the focus every episode. Riggs, his deathwish, and his turn around can also be given more depth, spreading the issues over several episodes.

The critical issue with a Lethal Weapon TV series, though, is the chemistry between the leads. In the movies, Gibson and Glover played off each other so well, a remake would be impossible. Yet, in the TV series, the impossible happens each week. The casting of Clayne Crawford as Riggs and Damon Wayans as Murtaugh brings in the chemistry as the two work well together. They may not play off each other the same way Gibson and Glover did, but they do bring a new approach.

Another issue is the passage of time. The pilot episode of the TV series aired almost thirty years after the first movie’s release. In that time, there have been changes in how police departments operate, especially when it comes to officers like Riggs who are suffering from mental health problems. The Captain’s attitude in the first movie, that Riggs is bucking for a disability pension, would have him written up by the staff psychiatrist. Instead, Riggs has regular sessions with the psychiatrist, Dr. Maureen Cahill as played by Jordana Brewster, with her word being what allows him to work. The plots of the first two movies would need heavy rewrites to be adapted as episodes, should the series chose to use them; the end of US involvement in Viet Nam was over forty years ago and Apartheid in South Africa ended in 1991.

The series changes a few details. Murtaugh’s wife is now a defense attorney. Riggs is now from Texas. Murtaugh isn’t so much hoping for his last years on the force before retirement to be quiet; he now has a pacemaker and is under orders from his doctor and his wife to take things easy. These changes don’t affect the core of the show; Murtaugh is still a family man who loves his wife and kids while Riggs is a family man who is despondent after losing his wife in a car crash.

The opening scene of the pilot episode demonstrates this clearly. During a hostage taking after a failed bank robbery, Murtaugh is on scene working to get the situation handled quietly, with the proper people in to talk the robbers into letting everyone go with no one coming to harm. Riggs takes matters into his own hands, delivering a pizza to the robbers and exchanging himself as a hostage.and freaking out his captors by provoking them into shooting him. That wasn’t the way the two met in the movie, but it sums up both characters well. The Lethal Weapon TV series is still, at heart, a buddy cop action/comedy, with one cop wanting to keep things quiet and the other with a deathwish, fighting crime in LA while causing millions in collateral damage.

* In 1989, South Africa was still under Apartheid, a system of government suppressing the black majority by the white minority. In Lethal Weapon 2, Riggs treated the diplomat as being no better than a Nazi. The distraction Leo and Murtaugh cause at the South African embassy is well worth seeing.

Last week, Lost in Translation looked at a fan-made audio drama, including the nature of audio plays. The post goes into greater detail about the needs of an audio adaptation. This week, Lost in Translation looks at another fan audio work, Star Trek: Outpost, from Giant Gnome Productions.

Like Starship Excelsior last week, Outpost is a Star Trek fan audio series set after the end of the Dominion War. However, Outpost is set on Deep Space Three, a neglected space station near the borders of both the First Federation, first seen in “The Corbomite Maneuver”, and the Ferengi Alliance. The relative calm of the sector compared to those abutting Klingon space, Romulan space, and the ones consumed by the Dominion War meant that Starfleet did what it could to keep the station running without spending too many finite resources. Commanding the station is Captain Montaigne Buchanan, an efficiency expert who has managed to keep the station going with fewer and fewer resources. Captain Buchanan is looking forward to his efforts at the station being rewarded with a promotion to Admiral. However, the transfer of Lt. Commander Greg “Tork” Torkelson from the USS Remington to become as the station’s Executive Officer, throws a few hitches into Buchanan’s approach. Torkelson, as the Exec, also gains command of the USS Chimera, an Oberth-class starship similar to the USS Grissom from Star Trek III: The Search for Spock.

Deep Space Three has a reputation for being a place where Starfleet personnel whose careers have nosedived go to, a collection of misfits and outcasts. The Chimera‘s Chief Engineer, Chief Petty Officer Bert Knox, is one such character. His goal is to keep the Chimera functioning, going so far as to salvage other decommissioned Oberths and to install alien technologies when the proper part isn’t available. Torkelson’s arrival, though, brings in new ideas on how to make Deep Space Three relevant again. Tork’s plans include re-opening parts of the station shut down to conserve power and resources, including the station’s mall. While Torkelson’s choice to run the station – Ferengi brothers Vurk and Tirgil – may not work out as well as he hopes, Deep Space Three is beginning to turn around from its reputation. Whether it can while Orion pirates, a rogue Klingon warrior, the return of the First Federation, and the general weirdness of the Pinchot Expanse are around is another question.

As mentioned last week, audio works need to create the setting solely through sound. Redundant, but success and failure hinge on making sure the audience knows what’s around through sound cues. Outpost succeeds here; the Chimera and Deep Space Three have different sounds, and starship and station both individualize their sets even further. The bridge of the Chimera has the proper sounds as expected and is different from the engineering section and sick bay. Likewise, Deep Space Three’s command centre is different from the station’s sick bay and from the mall. And when power is lost in one episodes, the background sounds disappear.

Like Excelsior, the cast of Outpost is more than compentent, and the two productions share a couple of voice actors, Larry Phelan and Eleiece Krawiec. Of note, the father-and-son team of Ben Cromey and Doug Cromey are fun to listen to as the Vurk and Tirgil, especially their rallying cry, “We’re gonna die!” Combined with the writing, the episodes of Outpost are compelling, with characters who have depth and can be empathized with, even when they’re not immediately sympathetic.

One thing the creators of Outpost do is create “minisodes”, or mini-episodes, when at conventions. They bring in netbooks with USB microphones and get volunteers from the audience to read parts in a script to show how a show is put together. Overnight, they edit the parts together, add in the sound effects and music, then present the minisode in a panel the next day. A good example of how the creators get this done is the minisode, “Ferengi Apprentice“, recorded at the Denver Comic Con. They had some problems with the recoding due to an unshielded cable interfering with a microphone, so the episode was redone, but both versions, the original recorded at the panel and the redone one, are included to show the differences.

Star Trek: Outpost is another fan-made production that takes pains to fit in with the original work. The effects are correct for the era, and the Chimera‘s mish-mash of parts include sounds from Star Treks of old. The result is a well-done adaptation that demonstrates how to adapt well.

The Eighties were a weird time in entertainment. Popular original works outnumbered popular adaptations for the first time in movie history. Regulations about advertising to children were relaxed, leading to animation adaptations of toys and anything that a toy could be made from. The latter meant popular movies became fodder for cartoons, even if the film wasn’t originally meant for children, like Rambo and Robocop. Lost in Translation has already looked at one animated adaptation from the era, Back to the Future. Another series, though, was more successful.

The Real Ghostbusters ran from 1986 until 1991, undergoing a title change to Slimers and the Real Ghostbusters in its third season. Despite being tied to the film, Ghostbusters, a court case between Filmation and Columbia/Sony forced the adaptation to change its name as Filmation had the name first, leading to adding The Real to the title. The Real Ghostbusters was licensed out to DiC, who farmed out the animation to several Japanese studios, giving the series a unique look. While Columbia had the rights to the movie by virtue of being the production company, the studio didn’t have the rights to the actors’ appearances, leading to main characters who had a passing resemblance to the original cast. One episode, “Take Two”, goes as far to explain the differences – the movie is an in-universe adaptation of the characters’ lives. Venkman even goes so far to remark that Bill Murray doesn’t even look like him.

The cast was small, cosnisting of five voice actors total. Arsenio Hall, best known now for his talk show, was starting out in his career when he voiced Winston Zeddmore, the guy the Ghostbusters hired when business picked up during Gozer the Gozerian’s invasion of New York. Maurice Lamarche, who has played roles such as the Brain on Pinky and the Brain, played Egon Spengler, scientist and inventor. Lorenzo Music, best know for playing Carleton the Doorman on Rhoda and Garfield the cat* in the cartoon based on the comic strip Garfield, portrayed Peter Venkman, scientist and all-around smarmy dude. Laura Summer got her first work as a voice actor playing Janine Melnitz and almost every other woman in the first two seasons. Frank Welker, who has made a career out of being a non-human voice, including Megatron in the original Transformers, among others, played Ray Stantz, scientist and inventor, Slimer, and a large number of other ghosts and supernatural creatures. Summer was replaced by Kath Soucie with the name change to Slimer and the Real Ghostbusters, but, for the purpose of this review, the renamed series will be treated as a separate work to come later.

Adapting Ghostbusters to a weekly format wasn’t a problem. The nature of the movie allowed for further adventures for the team. Ghostbusters was a business; the team could easily continue busting ghosts in an adaptation. Indeed, the “ghost of the week” plot carried the series. The series also treated the events of the movie as occurring in-universe. Peter did get slimed by Slimer at the hotel and the team did fight Gozer the Gozerian in the form of the Stay-Puft Marshmallow Man The goal to adapting well is to bring the core of the original, in this case, Ghostbusters into the new medium, even with all the restrictions on the adaptation. A number of elements of the movie just wouldn’t fly. Venkman’s lecherousness was toned down, but didn’t completely disappear; his casual cruelty was removed. Janine kept her crush on Egon until executive orders in Slimer forced the writers to excise it. Repeatable violence isn’t allowed, but very few children would have access to backpack-sized unlicensed nuclear accelerators*. The Ghostbusters also only shot at ghosts to pull them into their traps, reducing the potential harm further. The action could thus match what was shown on screen, complete with slime.

The main characters, despite not being allowed to look exactly like the original actors, did have enough details in common to make it easy to see who was who. Egon had glasses and the hair style, along with Lamarche’s Harold Ramis impersonation. Peter kept some of Bill Murray’s smarmy charm**. Summer recreated Janine’s accent. Ray still had his weight. Winston was still the workman of the group, the one who was more down to Earth. Equipment matched what was shown on screen. And to add to the accuracy, the design of Slimer in the 2016 reboot movie was partially based on his appearance in the cartoon.

As mentioned above, the series could have kept to a “ghost of the week” plot, mirroring the jobs the Ghostbusters had in the movie prior to the containment system shutdown and the fight against Gozer. The writers, though, went beyond that. The first episode, “Ghosts R Us”, had a trio of ghosts working a scam to drive the Ghostbusters out of business. The team fought Samhaim, the spirit of Hallowe’en, in “When Hallowe’en Was Forever”, written by J. Michael Stracynski of Babylon 5 and Thor fame. Even with “ghost of the week” plots, not every ghost was busted. Several were able to move on after completing a task that kept them tied to the land of the living.

Going beyond the above, the writers delved into myth, legend, and classic literature. Samhaim was but one character based on myth and legend. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse appeared in “Apocalypse — What, Now?” Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” was adapted as “The Headless Motorcyclist”, updating the legend for modern times. The team accidentally busted the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Yet to Come in “Xmas Marks the Spot”.***

Then there’s the adaptation within the adaptation, “Collect Call of Cathulhu”(sic). Written by Michael Reeves, the episode goes beyond just using the trappings. The episode acts as an introduction to the Cthulhu mythos as created by HP Lovecraft and other writers. Guest characters are named after other writers who had contributed to the Mythos; Clark Ashton after Clark Ashton Smith and Alice Derlith after publisher August Derlith. Lovecraft himself is name-dropped as the creator of the Mythos, with his writings in Weird Tales cited in-character by Ray. Cultists of Cthulhu appear, along with Spawn of Cthulhu and a Shoggoth. The episode even quotes Lovecraft, specifically “The Nameless City” – “That is not dead which can eternal lie,/And with strange aeons even death may die.” The episode climaxes with the awakening of Cthulhu, a being that, to quote Egon, “makes Gozer the Gozerian look like Little Mary Sunshine”, and the Ghostbusters fighting to just stop the Elder God, using the Mythos as a guide.

Even when not using classic literature for plots, the series has references to works that would be unexpected in a TV series aimed at a younger audience. In “Ragnarok and Roll”, the spell used to begin Ragnarok is the Elven inscription of the One Ring from JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. Franz Kafka’s Metamorphisis is referenced in “Janine Melnitz, Ghostbuster” as Janine reads out some of the jobs that have come in; “And some guy named Samsa says he’s possessed by the ghost of a giant cockroach.”

The Real Ghostbusters puts an effort into continuing the story from the movie, even while explaining away the differences. The series sets itself up as an alternate continuity where the original movie is a movie about the animated characters. The characterization builds from what was shown in the movie and expands on what was originally shown. The Real Ghostbusters is a worthy adaptation, taking into account the limitations imposed on it by the medium and expanding the ghosts thanks to not needing special effects beyond ink and paint.

* In an interesting twist, Bill Murray would later voice Garfield in the movies based on the strip.

** And if a child did have one, repeatable acts would be a minor concern.

*** While almost every TV series has had an episode based on Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, few had the Ghosts of Christmas running a gambit to teach a main character about the meaning of the season while still having Scrooge around.

The Universal monsters have become iconic since their first appearances. Lon Chaney as The Phantom of the Opera (1925) brought the tragic character on screen. Bela Legosi as Dracula (1931) provided the baseline for future cinematic vampires. Boris Karloff as The Mummy (1932). Claude Rains as The Invisible Man (1933). Lon Chaney Jr. as The Wolfman (1941). But the most endearing character may have been Karloff as Frankenstein’s Monster, in the 1931 Frankenstein. Karloff portrayed the Monster as a child, with a wonder about him as he discovers the world around him, turning the character from the vengeful being in Mary Shelley’s novel to a tragic victim hunted down by villagers.

The success of Frankenstein led to sequels, including Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Son of Frankenstein (1939), and Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948). Classics beget spoofs, much like the Abbott and Costello movie. With a film that has permeated pop culture, further parodies were due. Thus steps in Gene Wilder. Because both Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein had scared him as a child, Wilder had an idea for a script that rewrote the ending of both movies. He had set it aside when his new agent, Mike Medavoy, suggested that Wilder team up with Peter Boyle and Marty Feldman for a movie, actors that Medavoy also represented. Wilder reworked a scene from his script and submitted it.

The resulting movie, Young Frankenstein (1974), was co-written by Wilder and Mel Brooks, with Brooks directing it. Wilder starred as Dr. Frederick Frankenstein, pronounced “Fron-ken-steen” as he tried to distance himself from his grandfather Victor. Boyle played the Creature, portraying the Creature with the same child-like approach that Karloff used. Feldman played Igor, pronounced “Eye-gor”, the grandson of Victor Frankenstein’s assistant. Frederick is a famed neurologist, teaching at a university, when he is found by a lawyer for his grandfather’s estate.

Frederich makes the trip to Transylvania, meeting Igor and Inga, played by Teri Garr. Igor takes Frederick and Inga to the Frankenstein castle, which has been maintained by Frau Blucher, played by Cloris Leachman. Blucher is excited for Frederick’s visit; it’s a chance for Victor’s experiment to live again. The movie then follows the beats of the original movie, from the theft of a suitable body for the Creature to raising the body up to be hit by lightning to even the Creature meeting the little girl. All through this, though, are bits of humour, which is the true draw of the film. Young Frankenstein diverges from the original when Frederick makes the decision to take care of the Creature, unlike Victor’s attempts to subjugate his Monster. Frederick’s efforts lead to a song and dance number that goes wrong, leading to angry villages with torches and pitchforks. Even with that, everyone gets a happy ending, from Frederich and Inga to the Creature and Elizabeth, Frederich’s former fiancée played by Madeline Kahn, and even the angry villagers.

The beats aren’t the only factor at play. Young Frankenstein was filmed in black and white, making it an outlier where every other movie being made that decade was in colour. But it’s not just being in black and white that adds to the mood. The credits, the cinematography, the music, all were done in the style of the original movie. Brooks even had the original lab equipment on hand, thanks to Kenneth Strickfaden, who built the equipment for the original movie. Young Frankenstein maintains the mood of the original, thanks to lighting, while still being funny, a difficult task pulled off with style.

Beyond just aesthetics, the cast raised a good movie into a comedy classic. Wilder, Boyle, and Feldman worked well together. Wilder admitted in a bonus feature on the Young Frankenstein DVD that several roles were good until their actors took them, whereupon the roles became great. Kahn was originally thought of as Inga, but she preferred Elizabeth. Garr read for Inga in a German accent. Kenneth Mars took the role of Inspector Kemp and elevated what was written in the script. Leachman as Frau Blucher dominates her scenes. Even Gene Hackman in his role as the Blindman is more than what was written for the scene.

While Young Frankenstein is a parody, it builds off the original, using /Frankenstein/ as the base to hang the jokes on while still keeping the mood. Young Frankenstein works as a sequel of the original as much as it does a parody. The effort put in by Gene Wilder and Mel Brooks pays off.

As a genre, superheroes are dominating theatre screens. Characters from Marvel and DC are taking up residence on the silver screen, bringing in record box office returns. This wasn’t always the case. For the longest time, superheroes were relegated to television cartoons, TV series and movies much like Wonder Woman and Captain America and, before that, serials and animated shorts. The change from backup feature to blockbuster came with Superman: The Movie in 1978.

The character Superman first appeared in Action Comics #1 in 1938, heralding a new type of hero. Prior to Superman, most heroes were men of mystery, costume or not. Superman blazed the way for superheroes and is DC Comics best known character. Created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster*, Superman started with X-ray vision, super strength and super speed, being able to out run a locomotive and leap over tall buildings. As the comic continued, Superman gained more and more powers, some serious, such as from going from leaping to flying, some silly, like super typing skills. In his secret identity of Clark Kent, Superman worked as a mild-mannered reporter for the Daily Planet along side colleague, rival, and love interest Lois Lane and cub photographer Jimmy Olsen, all working under editor Perry White. Over time, Superman’s rogues gallery has grown, but his best known foe is Lex Luthor, corrupt industrialist.

Another way Superman set himself aside from the mystery men of the time was his origin. Superman was not of Earth but was the sole survivor of the destruction of the planet Krypton, sent to Earth as an infant. The young boy was found by Jonathan and Martha Kent, who adopt the child as their own. The raise the young lad, naming him Clark after Martha’s maiden name, and instill a sense of right and wrong, and have him keep his powers hidden.

The 1978 Superman is a retelling of his origin, from being sent from Krypton hours before the planet’s destruction to his first appearance in Metropolis and beyond. His early years, as a young boy and as a teenager, are given a strong focus, showing the influences that his parents and his time in Smallville have on him as a hero. In Metropolis, he gets dropped into the busiest newsroom in the city at the Daily Planet and is teamed up with Lois Lane. His first night in the tights sees him rescue Lois after the helicopter she’s in malfunctions and crashes, then nab a cat burglar halfway up an apartment building, stop armed robbers from getting away from the police, rescue a young girl’s cat stuck in a tree, and help Air Force One land after losing an engine.

Lex Luthor, during this time, is hatching a scheme to corner the market in seaside real estate. Step one was to buy up desert land in the west. Step two is to steal a nuclear missile that in step three he will detonate along the San Andreas fault, sending California into the sea. Lex recognizes that Superman is a potential threat to his success With the story printed with the interview Lois has with Superman, Lex figures out that shards of Krypton, kryptonite, could be lethal to the hero.

The movie stays faithful to the character of Superman, but not necessarily his powers. The ending involves Superman flying fast enough to go back in time, something that hadn’t been demonstrated in the comic. Helping to stay faithful is the casting of the characters. Christopher Reeve was an unknown actor at the time, but he was able to play both Clark Kent and Superman, showing differences between the two through voice and posture. In one scene, he straightens himself, gaining confidence and changing his voice enough to look like Superman, then deflates and slumps to go back to being Clark. Margot Kidder as Lois Lane protrayed the reporter as someone who not only can get into trouble but can also get out of most of that trouble. Gene Hackman, as Lex, with Valerie Perrine and Ned Beatty as henchmen Eve Teschmacher and Otis, showed the deviousness of the original character with chemistry among the three to carry their parts of the film. Marc McClure looks the part of Jimmy Olsen.

The cast isn’t the only factor turning the movie into a success. The scope of the film is epic, despite focusing on Clark. Lex’s scheme threatens the entire West Coast. The film even starts deep in space for the credits, coming in to Krypton, then follows young Clark on his trip to Earth. The music adds to the epic feel. The main theme even uses the syllables in the name Superman as part of the music.

As mentioned a while back, there are adaptations that become the definitive version of a work. Such is the case with Superman. It was the top grossing film of 1978, with people returning to see a man fly. Audiences use Christopher Reeve as the measuring stick to compare other actors in the role. The influence of Superman is still felt even almost forty years later.

* Joe Shuster was the focus of a Heritage Minute, a short film that features key times in Canadian history.

Marvel is riding high with the live action movie adaptations of its books. This wasn’t always the case. The first Marvel comic to be adapted for the big screen laid an egg. However, Marvel had a better record on television, with The Incredible Hulk lasting from 1977 to 1982. The success of Hulk brought the character into mainstream attention, with the series having an influence on the character’s movie entry in Marvel’s Avengers Initiative. That same success led to the first authorized Captain America movie*.

Captain America was a 1979 TV movie starring Reb Brown, known for his roles in Yor and Space Mutiny, as Steve Rogers. Steve is an former Marine turned drifter artist, hoping to travel along the California coast line in his van. He receives a telegram from Simon, played by Len Birman, who wants to talk to Steve about his father’s research. The Full Latent Ability Gain, or FLAG, is a serum that can maximize the human body’s potential. FLAG has a drawback; the serum causes cells to degenerate faster, leading to death. Steve declines the offer to test the FLAG serum on himself. and heads out.

Fate, however, brings him back. Steve finds his friend, Jeff Hayden, injured in his own home, attacked by a thug sent by Harley, played by Lance LeGault, on the orders of Brackett, played by Steve Forestt. Brackett wants a filmstrip** of Hayden’s work to use to complete a neutron bomb and wants Steve out of the way. Harley lures Steve with the knowledge of who killed Jeff. Steve shows up at the out of the way location at night, where Harley demands the filmstrip. In the ensuing chase, Steve is forced off the road and over a cliff on his motorcycle.

To save Steve`s life, he is given the FLAG serum while in ER. Unlike the previous test subjects, there is no cell rejection; the serum works. Steve’s healing accelerates under the influence of the serum, but he has no desire to find out what else FLAG has done for him. He doesn’t get to stay ignorant; Harley kidnaps him from the hotel, taking him to a meat plant. Steve breaks away from his captors and plays cat-and-mouse among the sides of beef. His newfound strength lets him take out Harley and his men, including through the use of a thrown slab of beef, the only object thrown in a fight in the movie.

Steve talks with Simon, who mentions the elder Roger’s nickname as a crusading lawyer, Captain America. Simon offers a job as a special agent, which Steve accepts. Simon arranges for extra equipment, updating Steve’s van, adding a new motorcycle with jet assist, and a bulletproof shield that can be thrown as a deadly weapon. While he tests out the new motorcycle, Brackett sends men to chase him down by helicopter. Thanks to the new motorcycle and FLAG-enhanced abilities, Steve manages to turn the tables.

Brackett is busy working on Hayden’s daughter Tina, using her to figure out where the filmstrip was hidden. He pieces together what Hayden meant when mentioning his wife with his final breaths and finds the filmstrip. Brackett takes Tina hostage and the filmstrip to his weapons expert, who can finish the neutron bomb with the information on the strip. The bomb gets loaded on to a truck and shipped out. However, Steve’s enhanced hearing picks up a clue on where Tina could be, leading to an oil refinery owned by Brackett.

Simon provides one last present to Steve, a costume to help hide his identity as Captain America. Cap heads to the refinery to rescue Tina and stop Brackett. He sneaks in but is spotted. The alarm sounds, but Steve’s enhanced abilities are no match for the guards. Tina is rescued, but the neutron bomb plot is revealed. With some research, the target is located. Steve and Simon fly off to stop Brackett.

A second made-for-TV movie, /Captain America II: Death Too Soon/, followed, with Reb Brown back as Cap and Christopher Lee as the terrorist, Miguel. Miguel holds a town in check with a virus that causes rapid aging. Unless paid or unless Cap can stop him, Miguel plans to gas a city and withhold the antidote, letting the city die of old age in hours.

The TV movies take liberties with Cap’s background. Captain America: The First Avenger shows the origins well, with Steve Rogers volunteering for a super soldier program and gaining super abilities as a result, and only being frozen after a fight against the Red Skull. In the comics, Cap is found by Namor, is thawed, and becomes one of the founders of the Avengers. That is a lot of backstory to fit into a two-hour TV movie, so the change to an former Marine makes some sense. Steve became an artist once thawed out, so that part is accurate. In 1972, thanks to the Watergate scandal, Steve gives up the role of Cap out of disgust with the government and becomes Nomad, a wandering hero. That storyline, though, only lasted a year. The change to California is explained by keeping costs down; the studio was based in the state.

In the Seventies, the main names when it comes to live-action superheroes were Wonder Woman, The Incredible Hulk, The Six Million Dollar Man, and The Bionic Woman, all characters with similar power sets – super strength and endurance, all easily portrayed with practical effects, camera angles, and sound effects. The cost of energy blasts in post could be prohibitive, as seen with the original Battlestar Galactica, but jumping higher than normal uses the simple camera trick of running the film of someone jumping down in reverse. A drifting hero working for the government covers all the TV series mentioned; it’s a concept audiences should be familiar with and works for Captain America.

Reb Brown, while not the best actor around, is earnest as Captain America and, just as important in a superhero series, has the physique needed. The earnestness helps when considering that Cap was often considered a Boy Scout in the comics of the time. The music by Mike Post and Pete Carpenter is very Seventies with brassy horns and doesn’t quite survive the passage of time. The concept, a hero working for a secret organization, is common, from the OSI in The Six Million Dollar Man and The Bionic Woman to the Foundation for Law and Government in the later series, Knight Rider.

Captain America and its sequel are very much Seventies-era made-for-TV movies, suffering from budget limitations. They take liberties with Cap’s background, but keep close to the characterization of the time. The needs of gaining a television audience forced some changes. The movies are definitely curiosities, and make a valiant effort, but fall short as adaptations.

* The Turkish film 3 Dev Adam, released in 1973, featured Captain America fighting Spider-Man and was not authorized by Marvel.

** A filmstrip is a series of still photos placed on a strip of photographic film as a means of presentation, much like an early version of a PowerPoint presentation, often with an accompanying recording on cassette, vinyl, or reel-to-reel with signals to let the viewer know when to change the slide.