During a discussion with Steve, the question whether there is a cycle happening, one first started in the Fifties. During the History of Adaptations, the Fifties were discovered to have a low number of original works, something that the Aughts shared. The Fifties also had a number of movie remakes, something the New Teens is seeing.

With the movies remade in the Fifties, the new versions took advantage of the change in filming technology. The Ten Commandments and Ben Hur: A Tale of Christ were both black and white silent films when they were released in the Twenties. Their remakes in the Fifties took advantage of the major advances in movie making – sound and colour. With both films being period pieces, nothing on screen needed to be changed beyond what was essential for the new technologies and grander scales available. The spectacle of both epics were enough to draw in the younger audience while those who saw the originals could see them again with the new dimensions of full colour and sound. Thirty years made a huge difference in the film industry.

Fast forward to now. The entertainment news is filled with remakes. Just from the older news posts for Lost in Translation, I get the following list:

Jem and the Holograms

The Equalizer

Ghostbusters

Predator

Indiana Jones

Blade Runner

Big Trouble in Little China

That doesn’t include films like 21 Jump Street, remaking a TV series, and all the Ninties movies being remade like Stargate. Again, the difference is thirty years. The advances in film technology aren’t as obvious, though. The use of computers for special effects has grown over time, but not all the works being remade will benefit from the advance outside the budget. Cecil B. De Mille remade The Ten Commandments because of the sound and colour. The movies listed above and the others are being done because of nostalgia.

It’s the thirty years that raised the question. Thirty years is enough time for a young man to work through the system to get to the point where he can make decisions on what to film. Thirty years ago was 1985, the middle of the decade with the most original popular works made. The chart from last week may help here.

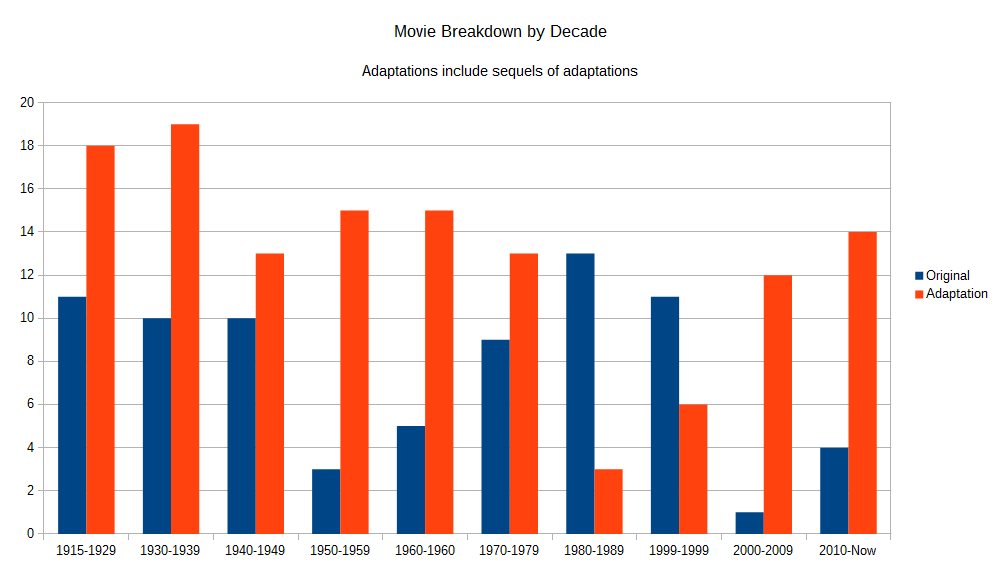

As pointed out last week, part of the issue with the complaints about adaptations is that the Eighties and Nineties, where the original works outnumber the adaptations, were anomalous. Today, if someone wanted to watch a movie from the Eighties, it’s not difficult. Between television reruns, home video and online streaming, chances are good that a movie from the Eighties is available. In the Fifties, those options weren’t available. Movies from Hollywood’s early years might make an appearance on television or appear at repertory cinemas, but the ease of finding them did not exist like it does today.

Is there a cycle restarting? It’s hard to tell. There isn’t enough data yet to make that call. The chart above shows that the New Teens are behaving in a similar manner to the Sixties, but this decade is only half over. A backlash against adaptations is building, but, again, the Eighties and Nineties were exceptions, not the norm, when it comes to original works. It is something to keep an eye on, though. If a cycle is repeating, noting the speed at which the elements appear helps work out how long a given segment will last.

The History of Adaptations

Twenties

Thirties

Forties

Fifties

Sixties

Seventies

Eighties

Nineties

Aughts

New Teens

Welcome to the history of adaptations. I’ve been looking at the top movies of each decade, analyzing them to see which ones were original and which ones were adaptations, and of the adaptations, what the source material was. I’m using the compiled list at Filmsite.org as a base. With the New Teens completed up to now, it’s time to figure out what all this means.

First, though, my methodology. I needed a start point, thus my use of the list at Filmsite.org. The list provided me with a base to work from. I chose the popular films, as according to box office, because the films should be memorable enough and have lasting impact on films even today. Even Ingagi, released in 1930 and pulled when it was discovered that the found footage was found in other movies, still has ripples in the form of Gorilla Grodd, who has appeared in the current TV series, The Flash. While box office takes reflect how much money a movie made at the theatres, it does ignore the effects of television airings and the sale and rental of home videos, both video tape and DVD/Blu-Ray. Some classic films, including Casablanca and Psycho, gain an audience long after leaving theatres. Popular films also may not be representative of the films released. There aren’t many Westerns on the list, yet the genre was a staple for several decades.

Going through every film released, though, would be a huge undertaking. The goal of the project was to discover whether movie adaptations were a recent approach or if it was something happening throughout the history of film. The Filmsite.org list starts with 1915’s The Birth of a Nation. One hundred years of film history to examine. I needed a way to get a sample of what was released. Again, the popular films may not be representative. Statistically, I haven’t run the numbers. In the more recent decades, studios have shown a tendency to follow the leader; if one studio has a breakthrough hit featuring an alien invasion/romantic comedy, every studio will make a similar film to get a piece of the action. Whether that holds true for the earlier years of Hollywood remains to be researched.

Throughout the project, I broke down the films into original and adaptations, making note of where a film didn’t quite fit into either. I placed sequels under original unless the sequel itself was based on another work. Movies like Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King and The Hunger Games: Catching Fire are both sequels and adaptations, both being based on books in a series. The categories aren’t perfect, though breaking the movies into finer categories would dilute the numbers to the point of uselessness. The most films in one decade was 29, in 1915-1929 and 1930-1939. The fewest, 13, came in 2000-2009, which was also the decade with the fewest original works on the Filmsite.org list. The graph below shows the number of original movies versus the number of adaptations by decade. On the left, in blue, is the number of original works. The right, in orange, is the number of adaptations.

As the above shows, only two decades had the number of original movies outnumbering the adaptations. With all the complaints about the number of adaptations, the Eighties and Nineties, still fresh in people’s minds, were the exception. My expectation when I started was that the early years would have a large number of adaptations as scripts for stage were repurposed for film, but the Fifties showed otherwise. The Fifties were the first decade to have a huge number of remakes, too.

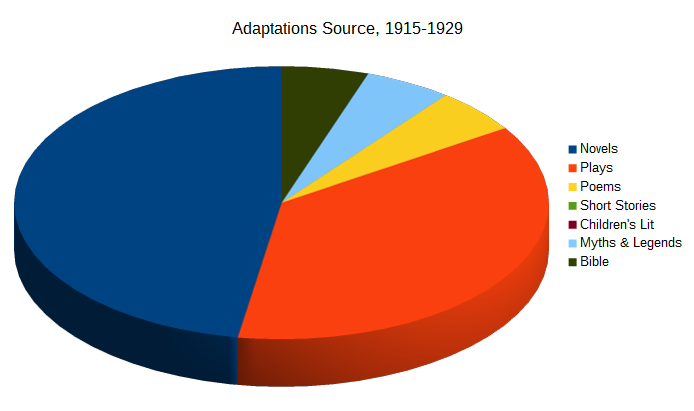

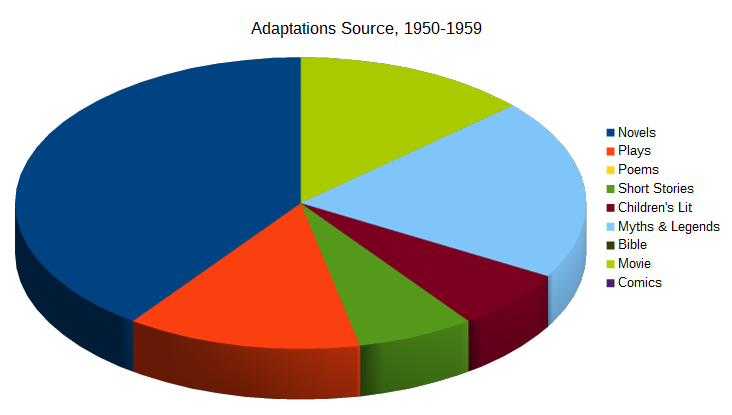

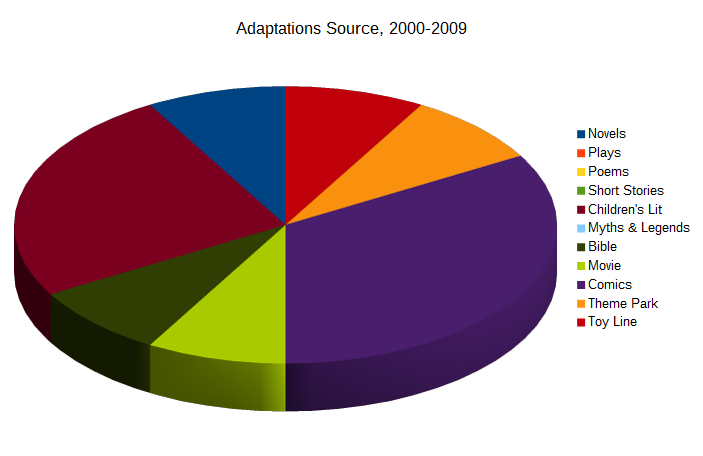

If the Eighties and Nineties were the exception, then why the complaints? The next few graphs might shed some light. I chose three separate decades, the Early Years, the Fifties, and the Aughts, to show what sources were used for adaptations.

Novels and plays are the bulk of the adaptations. Neither take over half, but the literary tradition is there. The other three sources, poems, myths and legends, and the Bible, aren’t that much different. The era is literary.

In the Fifties, novels and plays are major sources in adaptations, but other works are appearing. The number of remakes equal the number of movies using plays as a source. Myths and legends have a larger piece of the pie than in the Early Years. Children’s literature is a new source, thanks to Disney, but poems are still being used.

With the Aughts, the literary sources drop. Novels and plays combined equal the number of movies based on children’s literature. Comic books are a bigger source. The Aughts also had movies based on sources not seen in the previous decades – toy lines and theme park rides.

The Aughts may be showing why there is a complaint about the number of adaptations. The source work is far better known today. A movie based on one of Shakespeare’s plays passes the acceptance test. A movie based on a line of action figures is being made because either the toy line is selling well or the toy company wants to sell more of the toys, and thus can irk people. The same holds with using children’s literature and Young Adult works; there’s a feeling of catering to a younger audience that alienates older viewers.

Adaptations aren’t a new phenomenon. They’ve been around since the beginning of the film industry and will be around until the industry collapses. Film making is expensive. Studios need to pull in an audience, and, if done well, adaptations of popular works will draw in the crowd.

The History of Adaptations

Twenties

Thirties

Forties

Fifties

Sixties

Seventies

Eighties

Nineties

Aughts

Welcome to the history of adaptations. I’ve been looking at the top movies of each decade, analysing them to see which ones were original and which ones were adaptations, and of the adaptations, what the source material was. I’m using the compiled list at Filmsite.org as a base. Last time, the Aughts had fewer original movies than the Fifties, which had three, including the two Cinerama demo films.

The decade isn’t over yet, but the general trend has been for big budget adaptations based on comic books and Young Adult novels, or so it feels. Does this feeling hold out when looking at the popular movies so far this decade? Both Marvel and DC have a number of movies scheduled over the next few years, with Valiant getting in on the action. Movies adapted from Young Adult novels soared with the later Harry Potter films and the Twilight adaptations. Sustainability is in doubt, but the studios are making too much money to ignore the cash cow.

The top movies of the decade, by year, up to 2015:

2010

Toy Story 3 – sequel. Pixar’s approach to storytelling means that they won’t create a sequel unless there is a proper story to be told.

Alice in Wonderland – adapted from the 1872 Lewis Carroll story, Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There.

Iron Man 2 – sequel of an adaptation and part of the lead up to Marvel’s The Avengers.

2011

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 2 – both an adaptation and a sequel. The movie covers the latter half of the last book of JK Rowling’s Harry Potter series.

Transformers: Dark of the Moon – sequel of an adaptation of the Hasbro toy line.

2012

Marvel’s The Avengers – adaptation of the Marvel superhero team.

The Dark Knight Rises – sequel of the adaptation, The Dark Knight.

The Hunger Games – adaptation of the novel, The Hunger Games, by Suzanne Collins.

2013

The Hunger Games: Catching Fire – sequel and adaptations of the second book in the Hunger Games series by Suzanne Collins, Catching Fire.

Iron Man 3 – sequel of an adaptation.

Frozen – adaptation of the fairy tale, “The Snow Queen”, by Hans Christian Andersen.

Despicable Me 2 – sequel. The first movie, Despicable Me was an original work.

2014

American Sniper – adaptation of American Sniper: The Autobiography of the Most Lethal Sniper in U.S. Military History by Chris Pyle

Guardians of the Galaxy – adaptation of the characters and team as seen in Marvel comics.

2015

Jurassic World – adaptation. While intended as a sequel to the first three Jurassic Park movies, there are only two returning characters, including the island.

Avengers: Age of Ultron – sequel to the adaptations, Marvel’s The Avengers.

Inside Out – original but inspired by the daughter of the director

Furious 7 – sequel and part of the Fast and Furious franchise.

Of the eighteen movies listed above, four are original, including the sequels Toy Story 3, Despicable Me 2, and Furious 7. There are nine adaptations, including both Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Part 2 and The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, which are also sequels. The remaining five films are sequels of earlier adaptations. Naturally, the divisions weren’t easy to define. Jurassic World could be seen as a sequel of the previous Jurassic Park movies. I placed it as an adaptation because of how little it shared with the previous films. While Universal Studios counts the film as part of the Jurassic Park franchise, Jurassic World only has one character returning, and he was a minor one in the original movie. Thus, I’m placing Jurassic World into the adaptation category.

The source of the adaptations isn’t as diverse as the Aughts. Six movies were adaptations of comic books. Three were based on Young Adult novels. One came from a Michael Crichton work. Disney was the only studio to reach into the literature of the past for adaptations, using works by Lewis Carroll and Hans Christian Andersen. While comics haven’t had this strong a showing in previous decades, they aren’t a new medium. The Avengers #1 was published in 1963, bringing together characters from other titles, including Iron Man, who first appeared in Tales of Suspense #39 in 19591963*. Jurassic Park, published in 1990, is more recent.

Along with the above breakdown, there were ten sequels in the popular list. While Lost in Translation treats sequels as original works, continuing a story started in a previous film, the general movie audience may not agree with the assessment. The number of sequels, adaptations, and the combination of the two leads to the complaints that there are fewer original works. Yet, the Aughts had fewer popular original movies than this decade.

Next week, wrapping up the series.

* I misread the information at the link. Iron Man’s debut was in 1963; Tales of Suspense started in 1959.

The History of Adaptations

Twenties

Thirties

Forties

Fifties

Sixties

Seventies

Eighties

Nineties

Welcome to the history of adaptations. I’ve been looking at the top movies of each decade, analysing them to see which ones were original and which ones were adaptations, and of the adaptations, what the source material was. I’m using the compiled list at Filmsite.org as a base. Last time, the Nineties saw a slight slippage of the originality of the Eighties, but original works still outnumbered adaptations.

If the early days of AOL and the creation of the World Wide Web* allowed people to discuss films indepth, the normalization of the Internet meant that word of mouth could make or break a movie. A movie featuring two hot actors – Jennifer Lopez and Ben Affleck, linked via tabloids as “Bennifer” – should have had a good opening weekend. Instead, Gigli bombed at the box office as word of mouth sent warnings to avoid the film. Gigli set a record in 2003 for the biggest drop between opening and second weekend box office totals.**

I used “Weird Al” Yankovic as a barometer of popularity in the Eighties and Nineties. In the Aughts, he only had one song, “Ode to a Superhero“, released on the first album after Spider-Man hit theatres. His focus turned to the Internet, where popular memes now start. That change of focus is emblematic of how far into daily lives the Internet has become. Movies aren’t the trendsetters as they were in early days of Technicolor.

The top movies of the decade, by year:

2000

How the Grinch Stole Christmas – live-action adaptation of the Christmas story by Dr. Seuss.

2001

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone – adaptation of the popular children’s novel by JK Rowling. Harry Potter was a huge phenomenon, with people lining up outside bookstores when the new installments were released, something seen in the past for concert tickets for the biggest of the big name rock stars and with geek-friendly movies.

2002

Spider-Man – adaptation of the Marvel character seen in Spectacular Spider-Man and The Amazing Spider-Man.

2003

Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King – adaptation of the third book of JRR Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, The Return of the King. Also counts as a sequel.

2004

Shrek 2 – sequel of an adaptation. The first Shrek movies was based on the 1990 children’s book, Shrek!, by William Steig.

Spider-Man 2 – sequel to the 2002 adaptation, Spider-Man, above.

The Passion of the Christ – Mel Gibson’s controversial Biblical adaptation of the last days of Christ.

2005

Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith – the last of the Star Wars prequel movies.

2006

Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest – adapted from the Disneyland ride, “Pirates of the Caribbean”.

2007

Spider-Man 3 – like Spider-Man 2, a sequel of an adaptation.

2008

The Dark Knight – adaptation of the DC Comics character, Batman, as seen in a number of titles, including Legends of the Dark Knight and Detective Comics

2009

Avatar – original. James Cameron created an immersive world using 3D filming techniques, reviving the film process.

Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen – sequel of an adaptation of the Hasbro toy line, Transformers.

That makes a grand total of one original movie, Avatar. Of the remain films, there were six adaptations, five sequels to adaptations, and one movie, Return of the King, that counts as both sequel and adaptation. The obvious question, “What is the difference between a “sequel of an adaptation” and “a sequel and an adaptation”? The answer – source material. Return of the King was still based on an existing work, in this case, Tolkien’s novel. The movie relied heavily on the original work, which itself was a continuation of a story started in a previous novel. With the Spider-Man sequels and Shrek 2, the movies built on the previous movie but wasn’t necessarily based on the original work. The distinction is academic, but it does exist and will come up again.

The sources of the adaptations is another difference from previous decades. Literature and plays were the prime sources up to the Eighties. In the Aughts, three movies were based on children’s literature, with only one being animated. In the past, it was typically an animated Disney film that covered children’s books. Four movies were based on comic book characters, though three of those films featured Spider-Man. The Bible returned as a source, the first time since 1966’s The Bible: In the Beginning. Rounding out the literary sources is The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien’s fantasy epic.

What makes the Aughts unique is the use of unusual original sources, a toy line and a park ride. In the Eighties, Hasbro took advantage of a relaxing in regulations governing children’s programming, allowing them to work with Marvel and Sunbow to produce cartoons for several lines of toys, including Transformers, G.I. Joe, and Jem and the Holograms. Of those three mentioned, Transformers kept returning to television in one form or another, with little continuity between series***. With the animated series being a near constant, a live-action movie version wasn’t a surprise. The park ride, on the other hand, is Disney leveraging one of their existing properties in another field. The Pirates of the Caribbean wasn’t the only ride turned into a feature film. The Country Bears, The Haunted Mansion, and the recent Tomorrowland all began as Disney rides.

With just one more decade to go, it’s easy to see where complaints about Hollywood’s lack of originality comes from. After two decades where original works were in the majority, even taking into account sequels, the sudden turn around back to the level last seen in the Fifties makes the Aughts seem abnormal. As seen in this series, The Aughts and, as shall be seen, the New Teens arent’t unusual. The Eighties and Nineties were the exceptions, but since they are within recent collective memory while the earlier years are outside the pop consciousness, it’s difficult to realize how unique those decades are in the history of film. The Aughts also pull from sources not previously used as extensively. Prior to the Eighties, only animated films meant for children used children’s novels as a source. The Harry Potter phenomenon changed how people see children’s literature and opened the doors for movies based on Young Adult novels.

* Best cat photo distribution method ever created.

** The record has since been broken, first in 2005 by Undiscovered and then in 2007 by Slow Burn.

*** I’m simplifying this a lot. Transformers continuity is flexible and depends on the writer. Oddly, Beast Wars/Beasties is in continuity with the original Transformers cartoon despite the differences in time and in animation styles.

NBC has announced a remake of the Eighties series, Hart to Hart, with a twist. The original, airing from 1979 to 1984, starred Robert Wagner and Stefanie Powers as Jonathan and Jennifer Hart, a rich married couple whose hobby was fighting crime. Lionel Stander co-starred as the Harts’ butler and chauffeur. The twist? The new Hart to Hart will be a gay couple, Jonathan Hart and Dan Hartman*, a by-the-book attorney and a free-wheeling journalist, who fight crime.

With just the announcement, there’s some notable differences already. First, the new series has crime fighting part of the couple’s day job. In the original, as I mentioned, it was more a hobby or a side effect of their careers and wealth. The original Harts were independently wealthy, letting them go to wherever needed because they owned their own jet. Hart and Hartman may not have the mobility, but they will have more exposure to local crimes because of their jobs. Second, the wealth factor. Jonathan and Jennifer were rich. Jonathan and Dan should be comfortable enough to purchase or at least expense items, but unless either come from a wealthy family, there’s no butler. For the third difference, the obvious elephant in the room, Hart and Hartman are gay. Really, that shouldn’t be a problem, but with Kim Davis in the news the past few weeks, count on people complaining that there are gays on their TV.

The question, though, is why remake Hart to Hart instead of creating a new series?

Pros

Name recognition. Hart to Hart still rings a bell for the older audience and has a good ring to it. The name should pull in viewers who are curious.

Age. The last first-run episode aired over thirty years ago. The series is old enough and and has been off the air long enough that intimate familiarity is lacking. Hart to Hart also doesn’t have the same level of syndication as any of the Star Trek series. This lack of familiarity will let writers focus on the new characters without necessarily causing moments of, “But that’s not what Jonathan would do!”

What a twist! With same-sex marriage a huge topic over the past few years, coupled with the US Supreme Court overturning state level bans against those marriages, the series gains a new level of freshness. The younger audience, the people who poll very favourable to same-sex marriage, will appreciate the approach.

Cons

In name only. There are a number of key changes to the premise, as mentioned above. Changing the couple from opposite- to same-sex isn’t a problem, removing the wealth and thus one of TV’s better supporting role is. Again, if one of the pair is wealthy, the butler can remain, but nothing in the article mentioned anything about wealth. There is also nothing said about whether Hart and Hartman are married, though I have thoughts to share below about that.

It’s not its own work. This is the flip side of name recognition, above. The series can become a mainstream hit, showing a couple working together, living together, fighting crime, with the only difference being that they’re both men. But it’ll be known as a remake. Shouldn’t a ground breaking show be its own thing?

A few things I’d do with the show, which may or may not be planned already include working in the marriage and making sure the characters feel real instead of stereotypes. With the marriage, have it as a subplot through the first season. Hart and Hartman keep trying to get the wedding planned, but they keep getting sidetracked by investigations. Jonathan and Jennifer were an established married couple, having a few years of wedded bliss behind them; Jonathan and Dan don’t have that luxury because of legalities**. Given my druthers, I’d change Jonathan Hart to John Soul and change the title to Hartman & Soul, but I don’t work for a network.

If the show is successful, this could open up some older series to be remade with gay couples. Picture Simon & Simon*** remade, with the brothers turned into a gay couple who are private investigators; or McMillan and Wife as a lesbian couple, one being the commissioner of the San Francisco Police Department.

Jokes aside, I do hope the series does well, assuming it makes it to air. Quality work needs to be encouraged.

* Er, so shound’t the series really be called Hart to Hartman?

** Depending on the state. Set the series in California, and they could have been married since 2008.

*** If the Internet was around like today when Simon & Simon aired, the amount of Simcest fanfics would overwhelm the Supernatural Wincest fics.

Watership Down began as a tale told by Richard Adams to his daughters on car trips. The girls insisted that he write down the epic rabbit tale. In 1972, the novel was released by a small British publisher, Rex Collings, who couldn’t pay an advance but did get the novel out for review. A second edition was released in 1973, with an American edition coming out in 1974.

The story itself is about an epic journey of rabbits escaping their doomed home to found a new warren. Adams kept the narrative at the rabbits’ level, not explaining anything that the rabbits wouldn’t be able to understand. He even created a vocabulary and a creation myth for his rabbits. The locations in the novel came from the trips with his daughters and still exist. The title itself comes from the actual Watership Down in the UK.

The popularity of the book led Martin Rosen to try to adapt the work as a film. Early proposals included the use of puppets for the rabbits, but Rosen wanted to remain faithful. The result, he wound up not being just the writer, but the director and producer of the film, with no expierence as either, working on an animated feature.

The movie starts with the rabbits’ creation myth. Frith, the creator and sun god, created the sky, the stars, the world, and the world’s inhabitants. The first rabbit, El-ahrairah, and his descendants started to out-graze the other creations. Frith tried to warn El-ahrairah, but the first rabbit would not listen. Frith gave the other animals gifts, turning some into cats, dogs, hawks, and weasels who would prey on the rabbits. El-ahrairah ran and hid, but Frith found him and presented his gifts to the first rabbit – speed, listening, and cunning. El-ahrairah became a trickster. The animation of the myth is reminiscent of the art of ancient civilizations.

The art style changes to a more traditional look, though still rich, as the story starts. Two rabbits, Hazel and his brother Fiver*, are out eating and talking. Fiver, the runt of his litter, is nervous, moreso than most rabbits. He is psychic, a seer, though he can’t always understand the meaning of his visions. What he has seen is a blood red soaking into the warren, dooming the rabbits living there. The animation for Fiver’s visions is done in another style, powerful, overwhelming, and forboding. Fiver tells his brother, who believes him. Hazel tries to tell the Chief Rabbit about the oncoming doom. The Chief Rabbit dismisses the brothers; it is May, mating season, and moving the entire warren would be a huge upheaval over something the little rabbit is vague about.

Hazel, though, believes his brother. He organizes a number of other rabbits to leave the warren. The Chief Rabbit’s Owsla, the warren’s defense force, tries to stop the escape. One of the Owsla, Captain Holly, appears in front of Hazel’s band to take them into custody. A former Owsla officer, Bigwig, interferes, attacking Holly. Outnumbered, Holly runs off to get reinforcements. Hazel takes the opportunity to escape with his small band. Not every rabbit who tried to escape did, but Hazel has a core group, including Bigwig, Blackberry, Violet, the kit Pipkin, Silver, and Dandelion. As they leave, a sign that the rabbits can’t understand but the audience can shows that the are will be developed.

The rabbits run into the woods, avoiding a badger. Several obstacles are in their way, including a collie loose in the woods and a river that needs to be crossed. Bigwig suggests that the rabbits who can’t swim remain behind to fend for themselves but Hazel refuses to leave anyone behind. Blackberry finds a plank of wood that Pipkin and Fiver can sit on, with other rabbits pushing with their noses to get them across the river.

The journey is long and restless. Hazel presses the small band to keep going, trying to get distance between them and their doomed warren. Danger is always lurking; Violet gets nabbed by a hawk to never be seen again. Some of the rabbits start calling Hazel “Hazel-rah”, or “Chief Hazel”, though to tease. Hazel, though, is the leader of the band.

A potential sanctuary is found when the band meets with Cowslip, who offers the rabbits an empty burrow in his warren. The warren feels empty to the travellers and Fiver has a bad feeling about the place, like there’s a deception that he can’t quite pierce. Some of the rabbits note that the warren smells like man and press Cowslip for an explanation. Cowslip is evasive, but does offer flayrah (carrots) to the newcomers. His fellows, though, avoid talking to Hazel’s band. Fiver, overcome with nerves, runs away. Hazel follows to find out why, as does Bigwig. The former-Owsla is tired of the predictions of death and doom, and heads off to tell the other rabbits. He never makes it back. Bigwig gets caught in a snare. His fellows work to dig the peg holding the snare out, but it’s almost too late. Figuring out that Cowslip is using them to find and trip snares, the band leaves.

Fiver has another vision, this time of the new home. It is high atop a hill, where there are no men and no predators, where they can see anything approaching. The journey continues, but now with a goal. The band passes through a farm**. While the other rabbits rest, Hazel takes Pipkin to explore. They avoid the guard dog, remaining quiet as it sleeps. In the barn, they find a hutch filled with rabbits. Hazel talks with one of the hutch rabbits, a doe named Clover, but Pipkin spots a cat. The rabbits run, causing the cat to give chase and the dog to bark, and escape.

The journey continues. As they pass through a farmer’s field, Bigwig hears a voice calling his name. Fearing it is the Black Rabbit***, Bigwig cowers behind the others but knows that if the Black Rabbit calls, he must follow. However, it is Holly, wounded and exhausted, the sole survivor of the old warren. The former Owsla captain utters a single word, “Efrafrans” before collapsing unconscious. When he recovers, he tells the others what happened; men came with machines, filling in the burrows, trapping rabbits underground.

In another warren, a young doe named Hyzenthlay tries to point out to her Chief Rabbit, General Woundwort, that the conditions are overcrowded. There are too many rabbits in the warren. The rabbits can only go out at certain times, based on a mark placed on them. Woundwart refuses and, once the young doe is out of earshot, orders Captain Campion, the head of the warren’s Owsla, to keep an eye on her.

Back in Hazel’s band, Fiver finds the hill he saw in his vision, Watership Down. The band climbs up the hill where they find a tree providing space for new burrows. The band settles in. During this time, they discover that they have a neighbour. A seagull, Kehaar, has been injured by a cat and needs to heal. The gull and the rabbits overcome a language barrier, and Kehaar is nursed back to health.

Hazel discovers a new problem. While his fellow rabbits are safe, the warren is still doomed. Not one doe came with them. Even Kehaar notices the problem. Hazel convinces the gull to look for does, though he makes sure that Kehaar belives that it was his idea. The gull, his wings now healed, flies off in search. When he doesn’t return, the rabbits assume that he’s gone back to the “big water” he calls home. Hazel has a second plan, though.

Remembering Clover back at the farm, Hazel takes a few rabbits with him to break her and her hutchmates out. Eating through the hutch’s latches takes too long and the rabbits are discovered by both the cat and the dog. The dog sends up the alarm, getting the farmers out of bed. The men see the hutch open and the wild rabbits and shoot. Hazel is hit. The other rabbits return to the warren to give Fiver the bad news.

Fiver, though, has another vision telling him that Hazel survived. He follows his vision back down to the farm and finds his brother in a culvert. Kehaar returns, finding the psychic rabbit, and explains about the “little black stones” (shotgun pellets) in Hiver’s haunch. The gull removes the black stones, letting the rabbit brothers return to their warren.

Back at the warren, Kehaar tells Hazel about Efrafa, General Woundwart’s warren. Holly adds to the information, telling Hazel about the General’s tyrannical rule. As he recovers, Hazel comes up with a plan. Once healed, Hazel leads a raiding party, heading to Efrafa. Bigwig is sent to infiltrate the warren and gets appointed to Woundwart’s Owsla. While in Efrafa, Bigwig talks to several rabbits unhappy with the warren. One, Blackavar, was caught outside when he wasn’t supposed to and had his ears ripped before being set as an example to others. Bigwig also finds Hyzenthlay; he tries to convince the doe to leave with him. Hyzenthlay, like Fiver, is a seer, and sees the truth in what Bigwig tells her.

Outside, Hazel prepares for the great escape. He needs to get the rabbits past the iron bridge (a railway overpass) and down the river. Hazel finds a boat and remembers how the wood plank got Fiver and Pipkin across. He sends Kehaar to Bigwig to finalize the plans. Bigwig arranges the escape for sunset. Woundwart, though, is informed of Bigwig’s conversation with the bird, but not of the context. Even so, the General is suspcious and has his Owsla keep tabs on the big rabbit.

Sunset arrives. Bigwig leads a group of rabbits to the iron bridge, but Kehaar is nowhere to be found. Woundwart, with a wide patrol out to find the strangers, gives chase, catching up at the iron bridge. He and Bigwig fight. The clash is brief and ends when Kehaar swoops in at the General, giving Bigwig time to get the escaping rabbits away from the bridge and down towards the river. Hazel gets the escapees on the boat, but in the time it takes to chew through the rope holding it in place, Woundwart catches up. Bigwig delays the General long enough for the boat to get underway.

Hazel’s band, now much larger with the escapees, has a short breather before Woundwart catches up again. He heads out to meet with the General to negotiate, but Woundwart’s terms – return the escapees or death – are non-negotiable. Woundwart also wants Bigwig, the rabbit who dared to betray him. Hazel returns to the warrent and orders the burrows’ entrances plugged. Woundwart’s soldiers begin digging. Fiver falls into another trance and starts moaning about a dog loose in the woods. Hazel remembers the collie at the beginning of the trip and has an idea. He takes three of the fastest runners back to the farm.

With Hazel gone, the other rabbits hunker down, waiting for Woundwart’s soldiers to dig in. One of the entrances is re-opened, allowing the General inside. The twists and turns in the warren allow the defenders to attack from hiding, which is what Blackaver does to Woundwart. The General shows no mercy and kills the escapee before going deeper. He finds Pipkin and other kits and moves in. Bigwig emerges from the dirt and fights Woundwart for the third time.

At the farm, Hazel chews through the rope acting as the dog’s leash. The first runner takes off, getting the dog to give chase. The runners are spaced out; as one rabbit tires, another can take over leading the dog back to the warren. However, Hazel gets attacked by the cat. The cat holds him under her claws, waiting to finish the rabbit. Fortunately, the cat’s owner arrives to scold her.

The last runner, Hyzenthlay, arrives back at the warren, the dog still giving chase. She hides, but Woundwart’s soldiers are briefly surprised. One calls out a warning, but the dog kills the soldiers. Woundwart emerges from the warren, not believing that a dog could be dangerous. Seeing the dog, the general attacks. His body is never found and the General becomes a rabbit legend, a bogeyman to warn young kits.

The movie ends with the lderly Chief Hazel in a field watching over his warren. The Black Rabbit calls, inviting Hazel to join his Owlsa. Hazel follows, leaving his body behind, knowing that his warren will be safe.

As mentioned above, Martin Rosen wanted to adapt the book. His goal was to be as faithful as possible. However, the main challenge he faced was taking a 400+ page novel and condensing it into a 92 minute movie. Even animated, it isn’t possible to get the entire novel in. Rosen, though, managed to get to the core of the novel, the exodus from the doomed warren to Watership Down. He took pains to get details correct, even to the point of sending people to the locations in the novel to get photographs. The area hasn’t changed much since 1972 and even since 1978. The number of rabbits escaping the doomed warren was reduced, making it easier to keep track of which rabbit was which. In the novel, two rabbits, Holly and Bluebell, survived the destruction of the original warren, while only Holly survived in the film.

Minor changes aside, the core of the story remains. The story is still told from the rabbit’s eye view, and each character is recongizable – clever Hazel, nervous Fiver, and brave Bigwig. Rosen’s desire and effort to maintain the story comes through. Watership Down is a good example of being able to get to the heart of a novel without losing anything in the translation to film.

* The names both in the novel and in the movie are translated from Rabbit. The book goes into more details. Fiver gets his name because he was the fifth born, when rabbits can only count up to four; in rabbit, his name is “Little Thousand”.

** Nuthanger Farm, another real location.

*** The god of the moon and darkness, seen as a death god by rabbits.

The History of Adaptations

Twenties

Thirties

Forties

Fifties

Sixties

Seventies

Eighties

Welcome to the history of adaptations. I’ve been looking at the top movies of each decade, analysing them to see which ones were original and which ones were adaptations, and of the adaptations, what the source material was. I’m using the compiled list at Filmsite.org as a base. Last time, the Eighties turned out to be a complete reversal of the Fifties, with only three movies adapted from other works. Granted, the Eighties were known for sequelitis, but the continuing stories came from an original work.

The Nineties saw the introduction of the the biggest game changer to date, access of Internet to the masses. Prior, only government sites and universities provided email and access to Usenet newsgroups with their accounts. Companies like AOL, CompuServe, and GEnie brought the Internet to the home user. The Eternal September began the day AOL provided access to Usenet in September 1993. Compared to today, Internet access was slow and not very user friendly. Speeds were measured in bits. Downloads took days. Usenet, however, allowed people to talk about a wide variety of topics*.

Sequelitis continued, with varying qualities. Disney animation returned in force, having gone through lean years in the Seventies and Eighties. The disaster film made a brief comeback, though the genre succumbed to weak blockbusters that were more effect than story Computer generated graphics became affordable and reliable enough for regular use, allowing for shots that would be impossible to film using a practical effect. The advent of CGI effects allowed the disaster movie to return, with natural disasters replacing airplane disasters**.

As mentioned with the Eighties, there is a barometer of popularity. “Weird Al” Yankovic is still writing songs parodying movies. The different now is that the songs are coming out far closer to the movie than before. “Jurassic Park” and “Gump” both were released after the titular movies were. The cover of the 1993 album, Alapalooza, parodied the posters for Jurassic Park. “The Saga Begins“, though, was written before the release of The Phantom Menace and came shortly afterwards. Weird Al used Internet rumour, trailers, and other information to write the song in time for the movie’s release.

The top movies of the decade, by year:

1990

Home Alone – original. The antics of Macauley Culkins’ Kevin had people returning to see the movie multiple times during the Christmas movie season.

1991

Terminator 2: Judgment Day – a sequel to 1984’s The Terminator. Terminator 2 continued the story of the future war between man and machine, with humanity on the losing side.

1992

Aladdin – adaptation of the Arabian tale. Aladdin was Disney’s comeback movie but almost lost a nomination for best screenplay due to the improv of Robin Williams as the genie.

1993

Jurassic Park – adaptated from the Michael Crichton novel of the same name. Jurassic Park is one of the last movies to remain in theatres for over a year from release. The success of the movie has made it more difficult for other dinosaur films to succeed because of heightened expectations.

1994

Forrest Gump – adaptated from the 1986 novel by Winston Groom of the same name.

The Lion King – original but influenced by both the Biblical Moses and by William Shakespeare’s Hamlet. While Aladdin was a huge hit for Disney, The Lion King is considered the start of the Disney Renaissance.

1995

Toy Story – original. Pixar didn’t specifically base the story on the toys used.

Batman Forever – sequel to the 1989 adaptation, Batman and its sequel, Batman Returns.

1996

Independence Day – original. Roland Emmerich and Dean Devlin came up with the story while promoting Stargate. Independence Day combined the disaster movie with science fiction.

Twister – original. Part of the disaster genre’s resurgence. Twister was the first movie released on DVD.

1997

Titanic – original, using the sinking of the RMS Titanic as the backdrop for a doomed romance.

Men in Black – adaptation, based on the comic, The Men in Black, by Lowell Cunningham and published by Aircel.

1998

Saving Private Ryan – original, based on the D-Day invasion of Omaha Beach by American forces.

Armageddon – original. Armageddon is one of two releases dealing with asteroid strikes, with Deep Impact having been released two and half months prior.

1999

Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace – sequel, well, prequel to the 1977 movie, Star Wars.

The Sixth Sense – original. M. Night Shamalyan made his mark with this film with a then-unexpected twist.

Toy Story 2 – sequel to the 1995 animated film, Toy Story. Pixar’s reputation was cemented with the sequel.

Of the movies above, nine are original, two are sequels to original works, one is a prequel to an original work, four are adaptations, and one is a sequel to an adaptation. I have counted sequels as original works for this series. However, sequels of adaptations add a new problem. This isn’t the first decade to have such a film. Demetrius and the Gladiators from the Fifties was the first and was counted separately. Batman Forever will be counted separately as well.

The Star Wars prequel presents a new conundrum. It has been sixteen years since Star Wars: Return of the Jedi, so is The Phantom Menance a sequel or a reboot? Return of the Jedi was the end of the original story, at least on film. The Phantom Menace introduces new characters and shows one returning character at a much younger age. For purposes of tallying the numbers, The Phantom Menace will be treated as a reboot, thus an adaptation. These decisions will get less and less clear-cut in coming decades.

With those rulings, that makes eleven original, five adaptations, and one sequel to an adaptation. The percentage of original films drops, but the majority of popular movies for the Nineties are still original works, continuing the reversal started in the Eighties. Of the adaptations, there are two based on novels, one reboot of a movie, one adaptation of a legend, and one adaptation of a comic book. There is a variety of original works, which reflects the variety shown in the popular movies. That’s now two decades in a row where the originals finally outnumber the adaptations.

* It is best not to contemplate the variety. The hierarchy was fairly broad, but for those who were into topics that couldn’t get a large base for support, the alt.* hierarchy existed.

** There may never be another airplane disaster film. Airplane! is too well known, to he point where Sharknado 2 opened with an homage to the film. Airplane! has entered the pop culture subconscious to the point where the gags are known even if the source isn’t.

Big budget blockbusters. Tentpole pictures tested and refined. Studios so risk adverse they run a lunch order past a test audience before committing. Save the cat!

The desire and need for studios to turn a profit leaves little room for new cult classics. Granted, a cult classic is a film that gained a small, dedicated audience instead of having a greater mainstream appeal. Cult classics stumble at the box office but have longevity; The Rocky Horror Picture Show is one of the top grossing film of the Seventies as a result. Today, movies need to be hit over the opening weekend or they’re considered failures. Studios compete for opening days. The result – movies either soar or they’re bland; crashing and burning is rare.

The problem coming up is a lack of innovation. Avatar showed that 3-D could be used to create an immersive experience, but few films used the film technique for anything beyond cheap scares and roller coaster rides. James Cameron took the risk, but he had a number of successes, including Titanic, to persuade the studio that he could succeed. Avatar had people returning to theatres for second and third viewings. The lesson the other studios learned? People will go to 3-D movies. Not, “People will go out for immersive experiences,” or, “People appreciate innovative work when done well.”

The lack of innovation, especially when married to the Save the Cat approach to scripts, means that, after a while, all movies start looking the same. Does “Washed out hero is forced to work with others to save the world,” sound like Guardians of the Galaxy or Battleship? The difference is often just execution. Granted, this sort of thing comes in waves. The Seventies had disaster movies*; the Eighties had science fiction and sequels. The Western was a staple until Heaven’s Gate and still appears from time to time. Superhero movies aren’t going anywhere anytime soon. The Eighties, though, show more variety even with the sequels. Not every movie succeeded, but there was room for other movies outside the Star Wars sequels and Indiana Jones films, from Short Circuit to The Breakfast Club to UHF to Weekend at Bernie’s to Alien From L.A. Not every film succeeded at the theatres, but there was variety.

The core issue is money. Studios don’t want to lose $200 million on a bad movie. At the same time, studios don’t see a problem in investing $200 million in a movie that follows a checklist. Battleship wears the checklist on its sleeve. Even comedies are getting into increased budgets. The Hangover 3 had a budget in the same neighbourhood as Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace. On the flip side, Johnny Mnemonic (1995) was first developed for a $3 million budget and the studio turned the idea down, but then accepted it when the budget was upped to $30 million.

This isn’t to say that cult classics don’t happen. They’re rare. Few people set out to create one, and deliberate attempts to be a cult classic tend to fail. Today, though, the elements that turn a movie into a cult hit get weeded out during the checklist and further removed with all the audience testing that happens. A movie that fails at the box office isn’t necessarily bad; it’s just bland. Street Fighter: The Legend of Chun Li suffered this fate. Names could have been changed with no effect on the film. The earilier Street Fighter: The Movie may have been cheesy, but it was a better adaptation and it is more fun to watch**. Same goes with Flash Gordon; it was a fine cheddar, but the supporting cast and the soundtrack transform the film into the classic it is.

Today, the only way either Street Fighter or Flash Gordon could be made they way they were is if there was a big star attached. Granted, that is how Street Fighter was made, with Jean-Claude van Damme and Raul Julia. Today, much of the humour would be toned down or removed, turning the action-comedy to either pure action or an action-drama. The heart would be gone.

All of the above ignores television. The SyFy channel is the new home for B-movies, with such luminaries as Sharktopus, Lavalatula, and the Sharknado trilogy. Low budget monster movies with cheap CGI effects with an audience that wants to see that type of movie. It’s not the same; SyFy’s B-movies follow their own formula, mostly combining an animal with something else, either another animal or a natural disaster. Again, it comes down to execution and, for these movies, chutzpah.

Will the cheese return to the big screen? Eventually. Universal Studios managed to have a profitable summer without a non-franchise blockbuster. Outside Jurassic World and Fast and Furious 7, Universal’s line up has been of reasonable budgets, allowing for fewer losses on a movie that falls flat and huge profits for their successes, including Fifty Shades of Grey***. If other studios follow Universal’s lead, and give that a few years, the lower budgets means there’s room to experiment and try something different. An unsuccessful experiment won’t cost as much, especially if it does well on DVD. A successful one means that a larger budget can be assigned for similar in the future.

* Until Airplane! skewered the airplane crash genre so thoroughly.

** Raul Julia alone is worth seeing in the film. Having Adrian Cronauer as the Armed Forces Radio announcer was genius.

*** $40 million budget, over $560 million in box office take globally. That sort of success allows Universal to try another $40 million movie and not worry about failure.

Apologies to all. I had a post needing some finishing, but a hardware failure prevented me from getting to the file. There will be a post this weekend, barring a second laptop death.

Again, apologies. I did not want to have an off week so soon here.

Works adapted for television produce a new set of concerns. With movies, one of the big limitations is time; commercial film releases run anywhere between ninety minutes to two hours, with rare releases reaching the three-hour mark. A television series, however, has far more running time available to it than a feature film. Even accounting for commercials, there’s still twenty-two to forty-five minutes of show each episode. Long-running series may run out of original material before ending and will need to create new content*. With novels, especially those in a series, it’s possible to keep using existing content in a TV show. HBO’s A Game of Thrones is an exemplar of this sort of planning. Adapting a movie as a TV series, though, means that the show’s writers will be adding material. Today’s review looks at that situation.

In 1999, George Lucas released the first of the prequel movies, Star Wars Episode 1: The Phantom Menace. In the gap between that film and Star Wars: Return of the Jedi, released in 1983, numerous tie-in novels, comics, games, and toys were produced, creating the Star Wars Expanded Universe, or EU. The EU added more characters and settings to Star Wars. With the prequel movies filling out more of the history of the Rebellion, more EU products were created to fill in details not covered by the movies.

Such is the case with the CG-animated series, Star Wars: The Clone Wars. Set between Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the Sith, the series covered the Clone Wars at several levels, from the clones on the front to the politics of the Senate to the Jedi Council. The Clone Wars ran for six seasons, from 2008 until 2014, before ending. During its run, familiar characters mingled with new ones, showing the toll of the wars on all levels of Republic and Separatist society.

The Clone Wars started with a feature movie, with Jedi Knights Anakin Skywalker and Obi-Wan Kenobi and a number of clone troopers defending Christophis against the Separatist droid army. Young Ahsoka Tano is introduced as Anakin’s padawan, an attempt by the Jedi Council to try to teach Skywalker the dangers of his inability to let go of those he holds dear. Once the battle is won, Anakin and Ahsoka are assigned the task to retrieve Jabba the Hutt’s son, who has been kidnapped, to get the gang boss’s favour. The search leads to Teth, where the Separatists are holding the Huttlet. Anakin leads a force of clone troopers against the droids’ base, leading to a showdown against the assassin, Asajj Ventress, a protege of Count Dooku. Senator Padmé Amadala of Naboo finds out about Anakin’s mission and tracks down Ziro the Hutt on Coruscant, but discovers that he is part of the conspiracy against Jabba and the Jedi. With the help of C3PO, Padmé escapes and Ziro is arrested. On Tatooine, Anakin deals with Count Dooku long enough for Ahsoka to return the Huttlet.

The first season continues in a similar vein, at least to begin with. “Ambush”, the first regular episode, features Yoda and several clones on a mission to meet with the king of Toydaria. The episode sets the tone, showing that the clones, even though they look alike, are individuals, and Yoda treats them as such. As the seasons progress, the stories become darker, with the Jedi forced into becoming what they are not and Darth Sidious’ manipulations starting to pay off. That’s not to say that the first season was all light-hearted. Clones and Jedi died on-screen, and one Jedi fell to the Dark Side before being killed by General Grievous. The first season also showed why the Republic was fighting; the episodes “Storm over Ryloth”, “Innocents of Ryloth”, and “Liberty on Ryloth” depict what the droid army did with the Twi’leks and the liberation of their homeworld.

Being placed between the second and third prequel places a few limitations on the series. First, several characters had script immunity due to appearances in Revenge of the Sith. That’s not to say that the couldn’t inflict non-permanent injuries and psychological issues on existing characters. Second, new characters had to be written out in a way that their absence in Sith made sense. In particular here, Ahsoka could not be Anakin’s padawan by the end of the series. Likewise, Venrtess could not remain Dooku’s apprentice.

As mentioned at the beginning, adapting movies for television may mean adding new material. The Clone Wars did just that, but in a way that added to the original. New characters, like the aforementioned Ahsoka and Ventress, clone troopers Waxer, Boil, and Fives, and bounty hunter Cad Bane had their own stories that intersected with the lives of the original cast. In addition, minor characters like General Grievous had their roles expanded. Grievous, first seen in Sith primarily escaping before being defeated by Obi-Wan, is shown to be far more dangerous and far more callous, killing several Jedi and targeting medical frigates.

The series delved into other parts of the Galaxy Far Far Away. Seasons three and four showcased the Nightsisters, a sect of the Witches of Dathomir, and Asajj Ventress. Mandalore, the home of some famed armour, also had several episodes focused on it and its internal politics. The Galaxy felt larger as a result, away from Tatooine and Coruscant. At the same time, classic equipment seen in the original Star Wars began appearing, from the Y-Wings to the evolution of the clone trooper armour to look more and more like that used by stormtroopers.

The Clone Wars also managed to make Revenge of the Sith a stronger movie. Anakin’s fall to the Dark Side is shown throughout the series, as Palpatine introduces doubt that worms through his mind. The deaths of the Jedi as a result of Order 66 hit harder. No longer are they nameless characters in a montage but Plo Koon, Kit Fisto, and Aayla Secura, Jedi who have appeared and were developed as full characters in their own right.

As an animated adaptation, The Clone Wars took characters that were larger than life in movies and brought them in a new form on television. The animation evolved over the run of the series, noticeable even in the first season, and evolved to handle more difficult challenges. There were times when certain elements, such as the clone troopers, the battle droids, and General Grievous, were indistinguishable from what appeared on screen in Attack of the Clones and Revenge of the Sith. The eye to detail and the desire to respect the films came through. While it is true that Lucasfilm was still the studio behind The Clone Wars, not all of the studio’s releases matched the quality and care shown in the animated series.** The Clone Wars is well worth studying as a successful adaptation.

* I’m ignoring filler episodes here. Filler is more commonly seen in anime based on manga, where the series has to wait for new content to be created.

** The Star Wars Holiday Special stands out as a prime example here.